History of Kinsalebeg

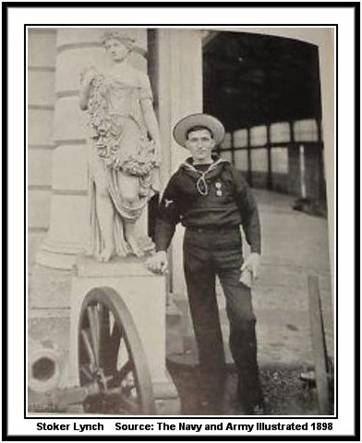

Stoker Lynch

Introduction

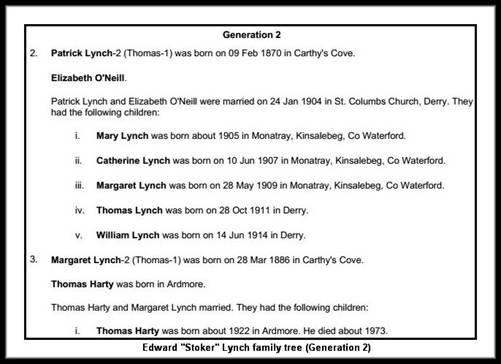

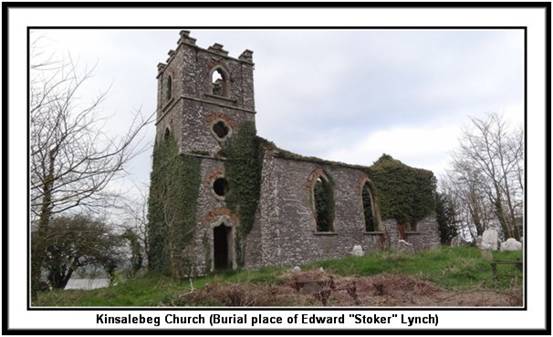

Eddie “Stoker” Lynch from the townland of Monatray is another Kinsalebeg hero from centuries past who with the passage of time is now largely forgotten in his native land. The following historic overview covers events in his relatively short twenty six year lifespan from his birth in Carty’s Cove Monatray on 4th April 1873 until his untimely death in Monatray on 1st February 1899 and subsequent burial with full naval honours in Kinsalebeg Church graveyard near Ferrypoint.

![]()

Most Notable Naval Personnel of the19th Century

When the British Navy drew up their list of the twenty five Most Notable Naval Personnel of the 19th century we find a predictable list of Lords, Sirs, Admirals, Vice Admirals, Lieutenant Generals, Commanders and Rear Admirals. However embedded in the middle of the prestigious list is the name of one Stoker Lynch of Monatray whose bravery became legendary in the British naval service and received widespread acclaim towards the end of the 19th century. The following is the list of the above twenty five most notable British naval personnel of the 19th century as indicated above. The list is not sequenced in any order of significance and is shown as it appeared on the original naval records.

- Sir William Henry White: K.G.B. Director of Naval Construction 1885.

- Admiral SirWilliam Garham Luard: K.G.B. President RN College 1882/5.

- Vice Admiral Sir Edward H Seymour: K.G.B. C-I-C on China Station 1897.

- Lieutenant Guant: Protected the King at Samoa in 1899.

- Rear Admiral Charles David Lucas: V.C. The first to receive the VC for gallantry.

- Admiral Sir John Edmund Commerell: V.C. G.C.B. C.I.C. Portsmouth 1888-91.

- Lieutenent Nicholson: D.S.O. Awarded DSO for conspicuous gallantry Crete 1898.

- Stoker Lynch: Mortally wounded trying to save a comrade. Awarded the Albert Medal 1897.

- Lieut. Gen. Sir Henry Brasnel: Tuson. K.C.B. D.A.G. Royal Marines. China, Egypt and Soudan 1856,82,84.

- Sir Henry Frederick Norbury: K.G.B. Inspector General of Hospitals and Fleets RN 1882.

- Surgeon Maillard: V.C. Awarded VC for rescuing a seaman under fire. Crete 1898.

- Rear Admiral Sir Gerard Henry Noel: K.C.M.G. A.D.C. to the Queen 1894-96.

- Chief Gunner Israel Harding: V.C. When an enemy shell entered his ship he plunged it into a vessel of water extinguishing the fuse.

- Rear Admiral Arthur Knyvet Wilson: K.C.B. V.C. A Lord Commissioner and Comptroller of the Navy. A.D.C. to the Queen 1892-95.

- Vice Admiral Sir Henry Frederick Stephenson: K.C.B. Commanding Channel Squadron 1897.

- G.J.Goschen: M.P. First Lord of the Admiralty 1871-74&1895. Chancellor of the Exchequer 1887.

- Commander S.C. J.Colville: Zulu War 1879. Egypt War 1882 Nile Expedition 1884&96-98.

- Commander Sturdee: Asst. Director Naval Ordnance 1893. Commanded Cruiser "Porpoise"Samoa 1899.

- Vice Admiral Sir J. A. Fisher: K.C.B. Crimea War 1854. China War 1859-60. Lord of the Admiralty 1891-97.

- Rear Admiral Lord Charles Beresford: K.C.B. Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty 1886.

- Lord John Hay: G.C.B. Lord of the Admiralty 1866, 1868-71. C.I.C. Devonport 1887-88.

- Commander Colin Keppel: C.B., D.S.O. Egypt War 1882. Commanded Nile Flotilla 1898.

- Sir F. B. Paget Seymour: Crimea War 1854-55 Egypt War 1882.

- Vice Admiral Lord Charles Montague Douglas Scott: Commander Australia Station 1889-92.

- Admiral Sir E.R. Fremantle: K.C.B.,C.M.G. C.I.C. China 1892-95. C.I.C. Plymouth 1896.

![]()

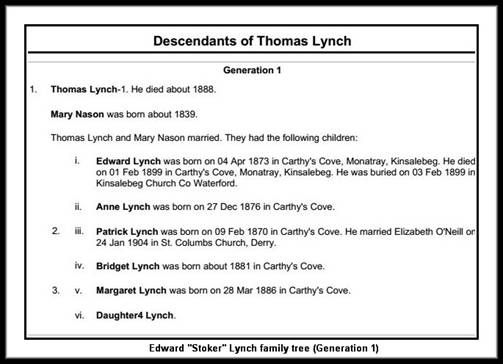

Lynch Family Background

Eddie Lynch was the son of Thomas Lynch and Mary Nason from Carty’s Cove, Monatray East, Kinsalebeg, Co Waterford. Thomas Lynch married Mary Nason (born circa 1837-1839) around 1866. They had six children namely Anne Lynch (born 27th Dec 1867), Patrick (born 9th Feb 1870), Edward (born 4th April 1873), Bridget (born c. 1881) and Margaret (born 28th March 1886) plus one other daughter. Margaret Lynch married Thomas Harty (Ardmore) and they had at least one son Thomas Harty (born Ardmore 1922, died 1973). Thomas Harty raised his family in London and served on frigates during WW2 including HMS Relentless. One report below indicates that there were two sons in the Navy in 1899 so it is possible that there were three sons born in total but we could only find records for two brothers. Thomas Lynch died around 1888 when his son Edward Lynch was around fifteen years old. In the 1901 census Mary Lynch (aged 62) was a widow and lived in Monatray with two of her daughters namely Bridget (aged 20, dressmaker) and Margaret (aged 15, scholar). Patrick Lynch, brother of Edward, was also in the British Navy for almost thirty years from 1892 up until after the end of World War 1 in 1920. Patrick Lynch married Elizabeth O’Neill in St Columbs Church, Derry on 24th January 1904. Some of their children were born in Monatray including Mary (born c. 1905), Catherine (born 10th June 1907) and Margaret (born 28th May 1909). Their other children were born in Derry, where Patrick Lynch was stationed for a period, including Thomas (born 28th October 1911) and William (born 14th June 1914). At the time of the 1911 census Elizabeth (Lizzie) Lynch, wife of Patrick Lynch, was living in Monatray with her mother-in-law Mary and her three children Mary, Catherine and Margaret. Margaret (Maggie) Lynch was the only child of Thomas and Mary Lynch who was still living at home with her mother in 1911.

![]()

Naval Service

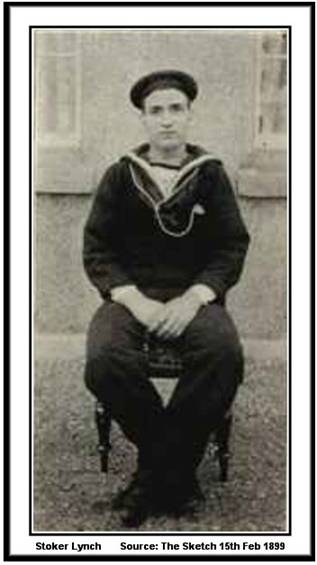

Edward Lynch joined the British Navy on 7th February 1896 and signed up for a twelve year period. His date of birth on signing up was given as 30th October 1871 which would mean he was twenty four years of age. However his actual age was twenty two as he was born on 4th April 1873. His personal details were recorded on signup as height 5ft 9ins, hair black, eyes hazel and fresh complexion. His place of birth was given as Mona Trea [Monatray], Youghal, Co. Waterford and the occupation given was seaman. He served initially as a stoker on the HMS Bellona which was a third class cruiser launched in 1890 and eventually sold in 1906. His naval base was Devonport near Plymouth Devon UK which was a major naval base and dockyard. His naval record was exemplary and his end of year naval reviews from 1896 to 1898 always indicated a VG (Very Good) character reference. In 1897 Edward “Stoker” Lynch or Stoker Lynch as he was better known was serving as stoker on HMS Thrasher which was a B-Class torpedo boat destroyer of the British Royal Navy built by Laird & Son in Birkenhead in 1895. She was one of what was known as Quail-class destroyers and operated eventually up to the end of World War 1 before being sold off at the end of hostilities. HMS Thrasher had a displacement of 395 tons and a length of 215 feet or 66 metres. She was fitted with triple expansion steam engines generating 6300 horse power. Her armoury included 1 x QF 12-pounder guns and 2 x 18 inch (460mm) torpedo tubes. Her full complement was 63 men.

![]()

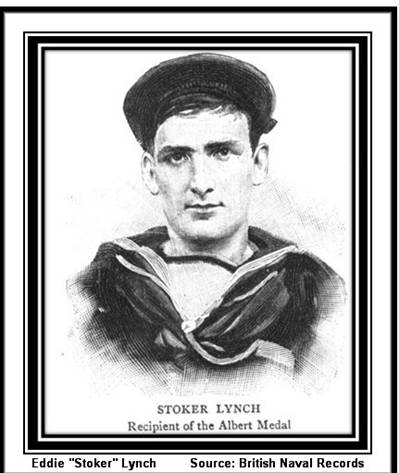

H.M.S Thrasher in Major Accident 1897

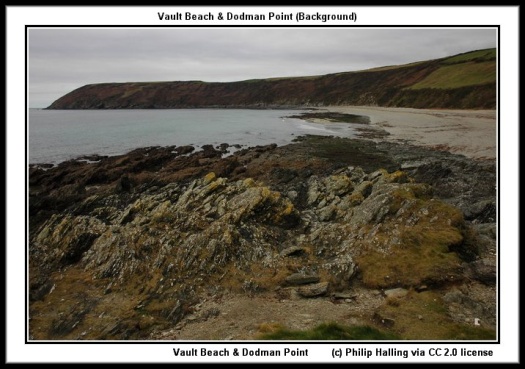

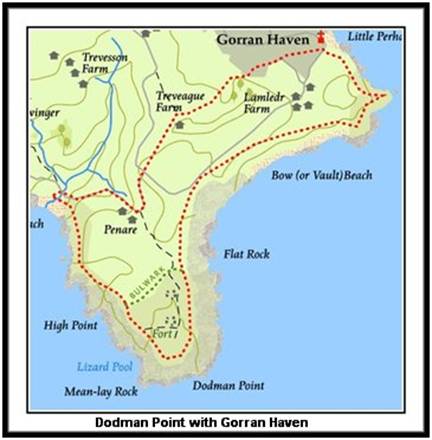

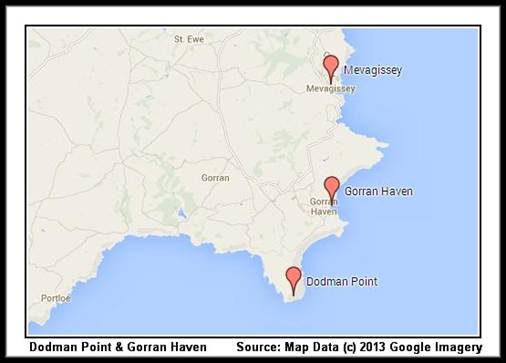

On Monday 27th September 1897 HMS Thrasher was one of three Royal Navy torpedo-boat destroyers which left the Royal Navy base at Devonport, Plymouth on a training mission. The other two ships in the training flotilla were the HMS Sunfish and the HMS Lynx and they were using Fowey as their headquarters during the four day training session. The ship was under the command of Commander Travers. The main purpose of the training trip was to enable stokers and other engine-room ratings to become familiar with the watertube boilers which were being fitted to new naval ships at that time. The ships left Devonport in good weather but a dense fog descended on the flotilla as they were cruising off the Cornish coast on Wednesday 29th Sept 1897 and the ships became separated. HMS Sunfish was travelling slowly when they spotted a headland which they recognised as the Dodman and managed to avoid hitting the rocks. HMS Thrasher had no forewarning of the danger ahead of them in the dense fog and hit the infamous Dodman Rocks between Fowey and Falmouth at a reputed speed of 12 knots causing serious damage. She was closely followed onto the rocks by the HMS Lynx which managed to escape serious damage and was subsequently able to make her return to Devonport under her own steam. The notoriously dangerous Dodman Rocks were the scene of many shipping disasters down through the centuries. Dodman Point itself is a 400 foot high headland which towers into the air near Mevagissey Cornwall. In 1896 a large granite cross was erected on the seaward side of Dodman Point which was both a memorial to those who had lost their lives at Dodman as well as being intended as a warning to future passing sea traffic. Unfortunately it did not prevent the HMS Thrasher and Lynx from foundering on the deadly rocks in 1897.

HMS Thrasher was extensively damaged in the accident and her back was broken on impact. Soon after the impact the main steampipe burst in a number of places causing a virtual inferno in the stokerhold. The steam pressure was a reputed 180 lbs per square inch which would have translated to a saturated steam temperature of around 380 degrees Fahrenheit escaping through the burst pipes. There were six stokers on duty at the time including Stoker Lynch. The chief stoker, Frederick Lang from Plymouth, was exiting the stokehold when the steampipe burst and he escaped without injury. Three stokers, including another Irishman Michael Kennedy from Ballylongford Co Kerry, were killed instantly by the scalding highly pressurised steam escaping from the burst pipes. The two other stokers killed instantly were John Hannaford from Plymouth and William Nicholls from Liskeard. The Belfast News Letter report stated:

“The unfortunate men must have died in a horrible manner. They were done to death in a rat hole, and the uplifted arms of the whole of them is an indication of their attenpts to shield their faces and optics from the first rush of blinding, scalding steam”.

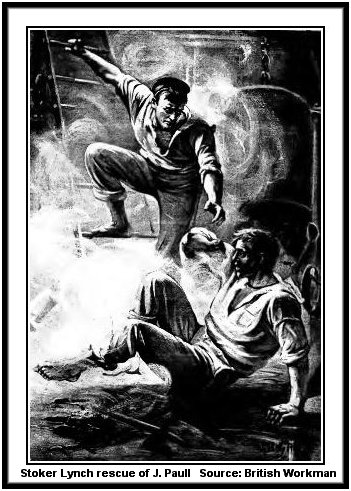

An injured Stoker Lynch managed to clamber out of the inferno and reached the safety of the deck. The starboard hatchway exit from the stokehold was impassable due to damage received in the original accident and Stoker Lynch was forced to make his exit through the port hatchway which was dangerously close to a break in the steampipe. He immediately realised that his colleague Stoker James Paull, from Teignmouth in Devon, had not managed to escape. He could hear Paull’s cries from the stokehold of the ship below and immediately went back down the treacherous port hatchway into the steaming inferno in an attempt to save his colleague. He would have been well aware that he was unlikely to survive a second time in the cauldron of the stokehold. Stoker Lynch managed to grab hold of James Paull, a big man by all accounts, and then drag him up the gangway ladder through the scalding steam jets to the upper deck. Stoker Lynch received the bulk of his serious injuries in the rescue of James Paull. The description of the brave event was subsequently reported in news media all around the world and the following description appeared in The British Workman1 in 1898:

“One of the stokers, named Lynch, managed by good fortune to make his escape from below, and reached the deck in safety. But in that terrible death-trap from which he had just emerged, one of his mates Stoker James Paul was caught, and was there being slowly scalded to death. His cries reached the ears of Lynch, who, without hesitation, went back to what must have appeared at the instant certain death. He plunged into the cauldron-like stoke-hold, and, seizing his comrade, dragged him by sheer force up the gangway ladder up to the deck”.

The two badly injured stokers, Stoker Lynch and James Paull, were brought ashore at Gorran Haven in Plymouth where they received further treatment for their injuries at the house of the coastguard of Gorran. Stoker Lynch managed to walk ashore at Gorran Haven despite his injuries and was apparently more concerned about the injuries of Paull than his own injuries. The report in the British Workman1 of 1898 describes the landing at Gorran:

“Lynch himself, in his daring act, did not escape scathless, for he, as well as Paul, was found to be badly injured, and both men were landed at Gorran Haven for treatment. While himself suffering intense pain, Lynch exhibited the greatest concern for his chum, Paul. The latter, sad to say, succumbed to his injuries, and Lynch himself was in extreme peril for a while, but thanks to his fine spirit and cheery disposition, as well as a robust constitution, he successfully pulled through”.

James Paull died of his injuries shortly after his arrival in Gorran. The death of James Paull had a profound effect on Stoker Lynch who was devastated at the death of his colleague. On Thursday 30th September the gunboat, Spider, arrived at Gorran from Devonport and on board were relatives of the deceased James Paull and also relatives of Stoker Lynch. Patrick Lynch, brother of Stoker Lynch, was amongst those who arrived at Gorran Haven. He was serving on board HMS Defiance at the time of the accident. The prognosis for Stoker Lynch was not great after the accident as outlined by the Belfast news Letter report of 1st October 1897:

“In his case [Stoker Lynch] erysipelas has set in, and the doctor has little hopes of his recovery. Dr Grier, the Admiralty surgeon stationed at Mevagissey, states that he never witnessed such splendid pluck as that exhibited by Paull and Lynch. On being landed the fishermen carried Paull in a sail, but Lynch, whose injuries were of a shocking nature, walked, supported by fishermen. All his thoughts were for his comrade Paull. When told this morning that Paull was dead his spirits broke down for the first time. Most of his injuries were received in rescuing Paull from the stokehold, Paull being a big man”.

![]()

Newspaper Reports of HMS Thrasher Accident 1897

The HMS Thrasher accident of the 29th September 1897 was reported extensively in news media around the world. We include details of three news reports which were typical of the coverage at the time. The newspaper report from the Hampshire Telegraph on the 2nd October is included in its entirety below and two other newspaper reports are included in the appendices at the end of this article. The reports are similar in content but each report has some different material so we are including all three reports as they give a good overview of events as they arose. These particular newspaper reports appeared in the days immediately after the accident and do not contain much detail concerning the actual rescue involving Stoker Lynch as the naval administration were slow to release operational details. Most of the detailed facts concerning the rescue incident itself did not come to light until made known later by naval personnel who were present on the HMS Thrasher on the ill-fated day.

Accident Report from Hampshire Telegraph on 2nd October 1897

The following is a report of the accident in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle newspaper dated 2nd October 1897:

Headlines: Naval Disaster: Thrasher and Lynx Ashore: Terrible Explosion: Four Stokers Killed.

Four Stokers Killed: “News was received at Portsmouth on Wednesday night that the torpedo-boat destroyers Thrasher and Lynx had gone ashore on the Cornish coast, in the neighbourhood of Fowey. These vessels belong to the flotilla that cruises off the Devon and Cornwall coast for the purpose of enabling stokers to become accustomed to the water-tube boilers, which are now being fitted in all new vessels. They left Devonport on Monday last to cruise off the Cornish coast, with instructions to make Fowey their headquarters. The weather was beautifully fine when they started from Plymouth Sound, but soon afterwards underwent a decided change, thick mists and fog being encountered.”

How the Accident Happened: “It appears from particulars received that the two vessels were cruising in the vicinity of Dodman Point on Wednesday, in a dense fog, the Thrasher leading. Suddenly, and with no warning of any kind, this boat ran ashore on the rocks in the neighbourhood of the Dodman, and became fixed. The accident occurred so unexpectedly that the officers of the Lynx had no time to alter the course of their vessel, which was following closely behind. Almost before they were aware of the Thrasher’s misfortune the Lynx was close upon her consort, and then she became in her turn fixed on the rocks. The destroyers are built of the thinnest steel and are quite unable to bear any strain. Almost as soon as the Thrasher touched ground one of the steam-pipes that supply the boiler with water exploded. The engine-room staff were immediately enveloped in steam, and one leading stoker and two stokers were scalded to death, two other stokers being very severely injured. One of the injured men has since encumbed.”

The Dead and Injured: “The list of men killed and injured is to hand, and is as follows:-

Killed: Second-class Leading Stoker John Hannaford, 12 St. Judes Terrace, Plymouth; Stoker W. Nicholls, Barn St. Liskeard; Stoker Michael Kenny, Balby, Longford (Ballylongford ?), Kerry, Ireland.

Injured:- Stoker Paull, The Strand, Telgnmouth; Stoker Lynch, Acre-place(?) , Youghal, Ireland.”

Statement by One of the Crew: “From the statement of one of the men it appears that the destroyers Thrasher, Lynx, and Sunfish left St. Ives at three o’clock on Wednesday morning for Falmouth. About one hour afterwards a thick fog came on, and the Sunfish lost her companions off the Longships. About half-past ten the Coastguards at Portloe heard syrens blowing, and on putting off in their boat they found the Thrasher and Lynx ashore at Dodman Head. Both vessels were badly damaged, and all movable gear was thrown overboard. Soon after striking, the boiler and steam-pipe in the fore compartment of the Thrasher exploded. There were six men in the stokehold at the time. The leading stoker escaped, whilst two others were severely hurt, and three poor fellows were scalded to death. The two who were injured were landed at Gorran Haven during the afternoon. The Thrasher was towed off by the tug Triton, and brought to Falmouth in a sinking condition. The Lynx, which is badly holed, got off without aid and proceeded to Devonport. The leading stoker rushed up the ladder just in time to save himself. The Sunfish, which put into Falmouth in the afternoon, also had a narrow escape from striking the Dodman Point, or “the Deadman” as it is locally known, land being sighted just in time to avoid a catastrophe.”

Heroism in the Stokehold: A correspondent at Mevagissey says that the crews of the two torpedo-boat destroyers were taken off by fishing boats from Gorran Haven, and were conveyed to Falmouth. The injured men were taken ashore and treated by Dr. Grier and Dr. Little at the house of Mr Mahoney, the Chief Officer of the Coastguard. Paull was the most severely injured of the men, and he died during the evening. This made the fourth death. Most of the injuries received by Lynch were sustained in rescuing Paull from the stokehole. Paull implored him to save himself, but he refused to desert his shipmate. He was greatly affected on learning that Paull was dead. It is stated that the pressure of steam at the time of the accident was 180lb (pounds), and it is evident that three of the men must have been killed almost instantaneously by the downward rush of vapour.

Prompt Assistance: As soon as Admiral the Hon. Sir Edmund R. Fremantle received intelligence at his official office he made arrangements for assistance being sent. A telegraph was at once despatched to Falmouth directing the Government tug Altua to proceed with all despatch to the scene of the accident. Meanwhile Staff-Captain Osborne, of the Dockyard, had made hasty preparations, and in a short time left the port in the Government tug Trusty, the destroyer Ferret also being despatched on a similar mission. The Trusty was the first to reach Dodman Point, and Staff-Captain Osborne was gratified to learn that both craft had floated on a spring tide. A glance at the Thrasher revealed that her injuries were of the most serious description, the centre of the vessel having evidently become fixed on the rocks. The Lynx, although injured, was not so much damaged, and it was decided that it would be safe for her to return to Plymouth, where she arrived in the evening. Preparations were at once commenced to take the Thrasher to a place of safety, and it was judged too risky to take her as far as Plymouth. In tow of the tugs Trusty and Altua she was accordingly taken round to Falmouth, where there are good docking facilities in connection with private yacht-building yards.

The Despatch of Medical Aid: Unusual steps had been taken to secure a large attendance of Naval medical officers at the spot, and in the afternoon Dr Clift, of Devonport Dockyard, with a surgery attendant, was despatched by special tug, taking with him a quantity of medical appliances, such as cotton-wool and oil for scalds. Her Majesty’s ship Pelorus (cruiser) and her Majesty’s ship Sharpshooter are cut on their trials, but a signal awaited them at the Breakwater Fort directing them to proceed to a spot off Gorran with all despatch and land their medical officers and staff. Captain Osborne, of her Majesty’s Dockyard, Devonport, also proceeded in a tug to Gorran, and having regard to his wide experience, and it was assumed in Naval circles that he would direct any salvage operations. The Curlow (gunboat), tender to the Cambridge, was held in readiness to tow lighters with provisions for the men engaged on the scene of operations, and the Naval Commander-in-Chief gave orders that the whole of the available docks at Devonport and Keyham were to be pumped out, and that workmen should stand by all night with a view to docking either the damaged craft if they should be conveyed to Devonport.

The Thrashers Damage: A Falmouth correspondent says that the Thrasher has sustained great injury about the bows 30ft from the fore head. Both her holds were embedded in the rocks, and every part of her was full of water. In the forward stokehold at the time were six men; one was also on the ladder, and he ran on deck when he heard the look-out man call out, “Land ahead.” The others were less fortunate, and as the boiler burst shortly afterwards, they were scalded.

The bodies of three of the men were in the hold. Everything movable in the Thrasher was removed to Gorran Haven fishing boats. She was towed off the rocks by the Triton tug about a quarter to four o’clock.

The Lynx in Dock: The torpedo-boat destroyer Lynx was docked on Thursday at Keyham dockyard, in the presence of Admiral Sir E. Fremantle, Naval Commander-in-Chief, and his staff. Men had been working all night preparing the deck for her report owing to a collision in the Channel, by which the torpedo-boat destroyer was injured and one of her crew drowned. The officers and crew of the Thrasher were subsequently turned over to the new destroyer Sparrow Hawk until the repairs of the Thrasher had been carried out in the Dockyard.

The Inquest Opened: The inquest on the bodies of John Hannaford, leading stoker, aged 26; Michael Kennedy, stoker, aged 21; and William Nicholls, stoker, aged 39, was opened at Mylor by Mr Carlyon, the Coroner of the district, on Thursday. The Coroner said it would be impossible to complete the inquiry that day, or even to go into the matter; therefore, after the Jury had viewed the bodies the inquiry would be adjourned. Frederick Lang, chief stoker of the Thrasher residing at Plymouth, gave formal evidence of identification, and the inquiry was then adjourned until next Tuesday, when the Court will assemble at Falmouth.

A Kindly Official Act: With kindly forethought for the relatives of the dead and the injured men, Admiral the Hon. Sir E.R. Fremantle ordered the Spider, instructional gunboat, to be placed at their disposal, and the vessel left on Thursday for Mevagissey, where Mrs Paull was landed and saw the dead body of her son, Lynch also was visited by his brother. The Spider returned to Devonport in the evening.

Two additional newspaper reports are included in Appendix A at the end of this article. The first one is an accident report from the Belfast News Letter on 30th September 1897 and the second newspaper report is an updated report from the same newspaper on the 1st October 1897.

![]()

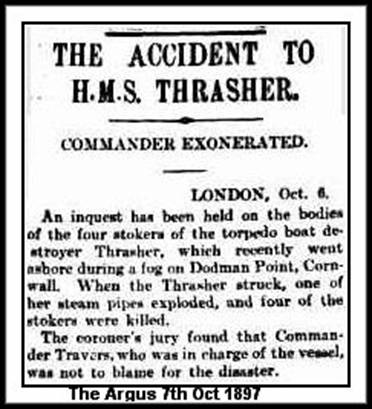

Inquest on Deaths from HMS Thrasher Accident Oct 1897

An inquest was held in October 1897 on the deaths of the four stokers who died as a result of the HMS Thrasher accident of the 29th September 1897. A verdict of accidental death was recorded for John Hannaford (aged 26), William Nicholls (aged 39), Michael Kennedy (aged 21) and James Paull. The coroner’s jury found that Commander Travers, who was in charge of HMS Thrasher when the accident happened, was not to blame for the disaster. HMS Thrasher was a rather unlucky ship as a short period before the Dodman accident it had apparently been involved in a collision with the cruiser HMS Phaeton. HMS Thrasher was on its way for a tour of duty in the Pacific at the time and had to return to port for repairs.

![]()

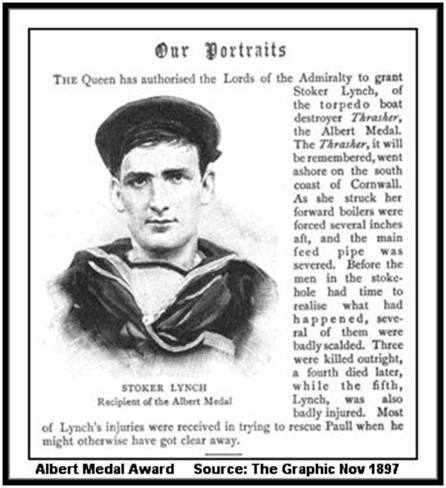

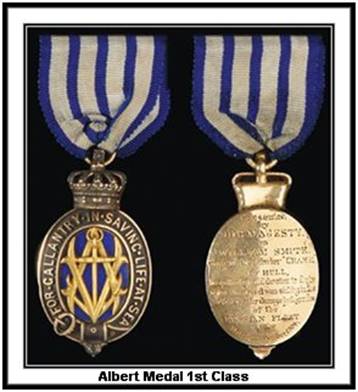

Albert Medal 1st Class awarded to Stoker Lynch 1897

In November 1897 it was announced that the Queen had authorised the Lords of the Admiralty to grant Stoker Lynch, of the torpedo boat destroyer Thrasher, the Albert Medal 1st Class for “outstanding bravery displayed in rescuing a comrade”. The Albert Medal 1st Class was the highest honour available at that time for bravery in life saving on land or sea. Stoker Lynch was the first naval seaman or person of the “lower deck”, as it was described at the time, to receive the 1st Class Albert Medal. The Albert Medal was introduced in 1866 and was named after Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert who died in 1861. The very idea of having two classes of bravery medal is somewhat incongruous and is probably a reflection on a past military class culture where officers and ordinary seamen or soldiers were two distinct classes. One of my childhood heroes was Tom Crean from Annascaul in Kerry who was a hero of the Shackleton & Scott expeditions to the South Pole in the early part of the 1900s. Tom Crean enlisted in the Royal Navy on 10th July 1893 which was a couple of years before Stoker Lynch who joined the navy on 7th February 1896. Petty Officer (First Class) Thomas Crean R.N and Chief Stoker William Lashley R.N were both awarded the Albert Medal 2nd Class for bravery during their extraordinary rescue trip during the ill fated Captain Scott expedition to the South Pole in 1911-1912. Tom Crean was awarded the medal for his outstanding gallantry in saving the life of Teddy “Taff” Evans who fell ill during the rescue trip but Crean and Lashley refused to leave him behind and saved his life by pulling him on a sledge across hundreds of miles of ice in atrocious weather conditions. Tom Crean was, until recent years, another largely unsung Irish hero but his story is now relatively well known in comparison with that of Stoker Lynch from Monatray. A commemoration statue of Tom Crean was erected outside his North Pole pub in Annascaul and books and plays have been written about this heroic Irishman.

The above image is the announcement that Queen Victoria had authorised the award of Albert Medal 1st Class to Stoker Lynch. This specific report appeared in The Graphic journal on the 13th November 1897.

The story of Stoker Lynch however is now virtually unknown in his native place and his body lies unmarked in the 800 year old graveyard of Kinsalebeg Church near Ferrypoint. Hopefully local schoolchildren will in future grow up with a greater knowledge of the lives, exploits and achievements of people like Stoker Lynch, William Wakeham, Anna Maria Haslam, Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior, Piaras Mac Gearailt, James Roch, Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior, Abraham & Jane Fisher, Sampson Towgood Roch, Peter Moor Fisher, Horace Sampson Roch and many others with Kinsalebeg connections from the past. The Albert Medal was replaced with the now better known George Cross in 1949 and in 1971 the Albert Medal ceased and all living recipients were invited to exchange their Albert medals for the George Cross. There were only twenty five naval recipients of the Gold 1st Class Albert Medal during the over 100 years it was being awarded from 1866 until 1971 which puts into perspective the bravery of Stoker Lynch – this period covered both World Wars. The total number of Gold 1st Class Albert medals awarded for all military categories of land, sea and air was only forty five medals in that same 100 year period. A special award parade was held at the Royal Naval barracks in Devonport at which Stoker Lynch was presentedwith his medal by the Naval Commander-in-Chief Admiral the Hon. E.R. Fremantle.

![]()

Presentation of Albert Medal 1st Class to Stoker Lynch 1898

The following article on Stoker Lynch appeared in The British Workman1 1898. It describes the presentation to Stoker Lynch of the Albert Medal 1st Class. The presentation was made by the Naval Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Edmund Robert Fremantle. The medal was conferred on Stoker Lynch by Queen Victoria in recognition of his conspicious bravery. The presenation took place at the Naval Barracks at Devonport in front of the officers and men present in the Naval Barracks. It was reiterated that this was the only Albert Medal 1st Class ever awarded to “a man of the lower deck” as well as being the highest honour that could be given for peace time service. The newspaper report was as follows:

“A Brave Stoker. The incident so strikingly illustrated on the first page of this number of The British Workman will still be fresh in the minds of our readers. It happened barely a year ago, on the occasion of the disaster to the two torpedo-boat destroyers, Thrasher and Lynx, on the Cornish coast. After the Thrasher had been practically ripped open by running over the Dodman Rocks, one of her boilers was thrust forward, the main steam-pipe burst, and there rushed forth a hissing, roaring torrent of steam, killing three men, and severely scalding several others.

One of the stokers, named Lynch, managed by good fortune to make his escape from below, and reached the deck in safety. But in that terrible death-trap from which he had just emerged, one of his mates Stoker James Paul was caught, and was there being slowly scalded to death. His cries reached the ears of Lynch, who, without hesitation, went back to what must have appeared at the instant certain death. He plunged into the cauldron-like stoke-hole, and, seizing his comrade, dragged him by sheer force up the gangway ladder up to the deck.

Lynch himself, in his daring act, did not escape scathless, for he, as well as Paul, was found to be badly injured, and both men were landed at Gorran Haven for treatment. While himself suffering intense pain, Lynch exhibited the greatest concern for his chum, Paul. The latter, sad to say, succumbed to his injuries, and Lynch himself was in extreme peril for a while, but thanks to his fine spirit and cheery disposition, as well as a robust constitution, he successfully pulled through.

On his complete recovery, a parade was held at the Naval Barracks, Devonport, at which Stoker Lynch was presented by the Naval Commander-in-Chief, Admiral the Hon. E.R. Fremantle, with the first-class Albert medal, conferred upon him by Her Majesty the Queen, in recognition of his conspicuous bravery.

The presentation of the Albert medal – the only one ever awarded to a man of the lower deck – took place, at nine o’clock, when the whole of the officers and men in the Naval Barracks, and the engineers, officers, and engine-room ratings of the Fleet and Dockyard Reserve were drawn up. A guard of honour of the Royal Marine Light Infantry received the Port Admiral, who was accompanied by the Hon. Lady Fremantle.

Admiral Fremantle , addressing the officers and men assembled, said he was there that day to present in the name of her most gracious Majesty the Queen the Albert medal of the first class to a man who richly deserved it. It was the highest honour that could be given for peace service.”

![]()

Heroism in the Stokehole 1898

The following description of the events surrounding the accident on the Thrasher was printed in the Colonist newspaper on 26th February 1898. It decribes how Stoker Lynch “must have plunged the forepart of his body into what was practically a boiling cauldron”.

“The Queen has conferred the decoration of the Albert Medal of the first class on Edward Lynch, stoker of Her Majesty’s ship Thrasher. The following is the account of the services in respect of which the decoration has been conferred:- At 3 a.m. on 29th September, the torpedo destroyer Thrasher, with the Lynx and Sunfish in company, left St. Ives on passage to Falmouth. In the thick and foggy weather, which was subsequently met, the Thrasher, followed by the Lynx, grounded at Dodman’s Point, causing serious injury to the boilers and the bursting of the main feed-pipe. A falling tide caused the Thrasher to heel over to about 60 degrees. The ship’s company was therefore landed on the rocks, a few men kept on board with boats ready to land them. There were six petty officers and men in the stokehole. Of these the chief stoker happened to be coming on deck by the starboard hatchway at the moment of striking, and escaped. This hatchway became distorted by the doubling up of the deck, preventing further egress. Stokers Edward Lynch and James H. Paul were compelled to escape by the port hatchway, close to a break in the steam-pipe. The hatchway, through which they passed was partially closed up, and Paul was unable to follow Lynch, who then, lying or kneeling on the deck, reached down into the escaping steam and drew Paul, who was on the ladder, up to the upper deck. Lynch was shortly afterwards observed to be badly scalded about the head, arms, and upper portion of the body in his rescue, the skin hanging off his hands and arms. Oil and wool were applied to alleviate the pain, but Lynch called attention to Paul, whom he wished attended to first, saying that he himself was not much hurt, but Paul was very bad. Neither man had said anything or called any attention to his injuries until this time although quite five minutes had elapsed since the accident. The surgeon who attended Lynch and Paul reports that the former, though very badly scalded and in great pain, would not allow his assistant or himself for a considerable time to do anything for him saying, “I am all right; look after my chum.” The manly conduct of Lynch induced the surgeon to make inquiries concerning the rescue of Paul from the stokehold, and he found that Lynch with difficulty released himself from the hatchway (much narrowed by the accident), lay down, and leaning into scalding steam, caught Paul and dragged him up through the hatchway, and in this way received his own injuries, which are such as to show that in rescuing his comrade he must have plunged the forepart of his body into what was practically a boiling cauldron. It appeared that Lynch in a most heroic manner had previously sacrificed his own opportunity of quitting the stokehold in order to aid his comrade Paul in escaping. Paul subsequently succumbed to his injuries, and Lynch for a long time was not expected to recover.”

![]()

Popular Hero and the Pledge 1898

The Daily News in May 1898 reported on a meeting arranged by a Navy Flag Captain when he invited the famous Agnes “Mother” Weston to speak to his men. Agnes Weston or Mother Weston, as she was popularly known, was a philanthropist and promoter of the temperance movement in naval circles including Portsmouth, Devonport etc. She joined the Royal Naval Temperance Society and was allowed to visit sailors on warships and talk to the crew to promote temperance. She was involved in establishing the first “Sailors Rest” home in Devonport in 1876 and subsequently in Portsmouth and other sea ports. She became known as Mother Weston as she was constantly concerned and interested in her sailors’ welfare and in particular the drink culture prevalent in naval circles. She encouraged many sailors to take the pledge and was apparently responsible for the closure of many pubs in Portsmouth and Devon due to lack of custom. The following is an excerpt from articles in May 1898 regarding the above meeting where Mother Weston addressed a group of naval staff:

“Not so long ago a Flag Captain actually invited this admirable woman (Agnes Weston) to address his men. By the way, Miss Weston described her experiences on this occasion with much eloquence, for amongst them was that heroic stoker Lynch, who, though scalded and writhing himself, was the last man out of the Thrasher (the incident was chronicled in every news-sheet a few months ago), and when taken ashore the last man to accept the doctor’s aid. “See to my chum first.” Miss Weston was unaware that he was present, perhaps thought he had succumbed, but had made some allusion to his gallantry. Then suddenly rose a roar: “ Stand up, Lynch !, Stand up, old fellow, and show yourself.” And up rose Lynch and said: “I have not been a drinking man, but my temptations are very great; I can get as much drink as I like without paying for it; now I can get free drinks anywhere, and if I become a drunkard it would break my mother’s heart. I should like to sign the pledge.” He did so and one hundred men followed his example. He was not only a brave man, but a true worker, using his influence with the other young stokers to get them to steer clear of the drink rocks. As Miss Weston very truly declared, scoffing colleagues couldn’t call him a waterbutt or milksop. He was known to be a true hero.“

![]()

Health Report on Stoker Lynch in July 1898

Edward Stoker Lynch spent a considerable period in the Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse getting treatment for the injuries he received in September 1897. On two or three occasions he was reported to be on the point of death but he rallied in a remarkable manner according to reports and was allowed home to Monatray, Co Waterford before Christmas 1898. At this point he was apparently suffering from consumption brough on by his injuries. The following article in the Freeman’s Journal in July 1898 gives an update on the state of health of Stoker Lynch in mid 1898. The article commends the “unobtrusive modesty of Stoker Lynch with the blatant self-advertisment and money-grabbing of some more recent recipients of decorations for bravery whose achievements do not deserve mention in the same breath as his”. This is a thinly veiled attack on Sergeant George Findlater who received the Victoria Cross for bravery for continuing to play his pipes, despite serious foot injuries and opposition gun fire, during the Battle of the Dargai Heights in 1897. The reference to “money-grabbing” was in connection with Findlater’s decision to augment his army disability pension by touring the music-halls playing his pipes. This activity was frowned on by the haughty military authorities. We include further details of Findlater later and the following is an excerpt from the Freeman’s Journal article in July 1898:

“I regret to say that Stoker Lynch, the gallant Youghal (sic) man whose splendid heroism on the occasion of the explosion on board of the torpedo destroyer Thrasher was acknowledged by conferring upon him the highest decoration for bravery known in the Navy, is lying gravely ill at the Naval Hospital at Stonehouse. He got seriously injured in his intrepid dash into the scalding steam of the engine room, and it is feared that his constitution has been so much undermined that he is failing into consumption. It is grateful to compare the unobtrusive modesty of Stoker Lynch with the blatant self-advertisment and money-grabbing of some more recent recipients of decorations for bravery whose achievements do not deserve mention in the same breath as his.”

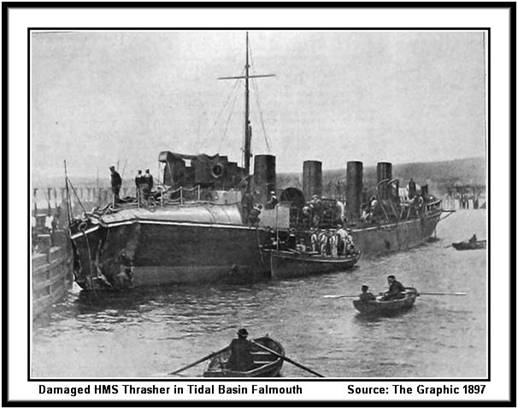

The following image is from The Graphic journal of 9th October 1897. It shows the damaged HMS Thrasher moored in the Tidal Basin, Falmouth after the accident.

![]()

Future Prospects for Stoker Lynch July 1898

There were numerous news articles on Stoker Lynch in the period from 1897 to 1899. The following article in The Engineer, dated 24th June 1898, suggested a possible job opportunity for him after his expected forced retirement from the naval service due to ill-health. The suggested job was that of gate-keeper at Balmoral Castle but unfortunately Stoker Lynch never regained his health to a point where he was able to work again:

“Stoker Lynch, whose heroic attempt to save a comrade on the occasion of the Thrasher disaster, would, had he only happened to have been a Highlander soldier instead of a “poor devil” of a stoker, have earned him as much glory as Findlater of Dargai and the music-hall, has been seriously ill at the Stonehouse Naval Hospital, and is now reported to be developing consumption. Stokers, as a class, are not the most agreeable people in the world, but they have produced quite as high or higher percentage of heroes as any department of the public service. The gate-keeper’s post at Balmoral, declined by Piper Findlater, might be bestowed upon many a less worthy man than Stoker Lynch, presuming, as is all too probable, that he will be invalided out of the Service. The engineers’ department does not get its due need of public appreciation, or anything like it, and it is quite time that something was done to rectify the omission. The present is an excellent opportunity. – The Engineer.”

The Findlater mentioned in the above article was Sergeant George Frederick Findlater, a Scottish piper in the Gordon Highlanders, who received the Victoria Cross for bravery during the Battle of the Dargai Heights in 1897. He was apparently shot in the feet during his regiment’s advance on opposition lines during the battle. He was unable to walk but despite his injuries and exposure to enemy fire he continued to play the pipes to encourage the advance of his battalion. He became a public hero after the battle and was awarded the Victoria Cross. Findlater decided to supplement his Army pension by touring the music-halls playing his pipes for money. This caused outrage in the British military establishment who believed that this was not a dignified pursuit for an injured Victoria Cross winner. George Findlater also apparently turned down the offer of the gate-keepers position at Balmoral according to the above article. As a result of the growing controversy George Findlater eventually gave up the “extra-curricular” activities and retired to his farm.

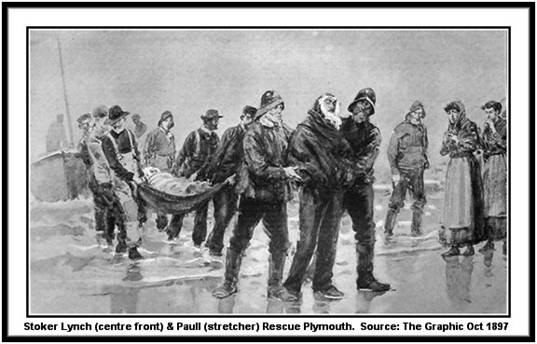

The following is a drawing of the injured Stoker Lynch being aided ashore by two fishermen (centre front) in Mylor Plymouth after the HMS Thrasher accident. His colleague and good friend Stoker Paull is being carried ashore on a stretcher by a group of fishermen. The drawing appeared in The Graphic journal of 9th Oct 1897.

![]()

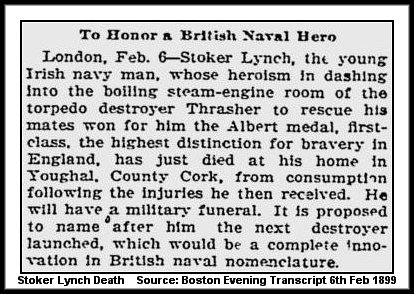

Death of Edward Stoker Lynch on 1st February 1899

Edward Stoker Lynch unfortunately did not get much time to enjoy life in his homeplace of Carty’s Cove after his discharge from the Royal Naval Hospital of Plymouth at the latter end of 1898. He died at his home in Carty’s Cove Monatray on 1st February 1899 and was buried with full naval honours at Kinsalebeg Church on 3rd February 1899. His death was as a direct result of the injuries he received in September 1897 on the torpedo boat destroyer HMS Thrasher. Agnes Mother Weston of the Sailor’s Home wrote as follows:

“When, after a long period of suffering, in the Royal Naval Hospital at Plymouth, where we constantly visited him, he was removed to his home in Ireland, we felt sure that the end was not far off. The Government were going to give him a pension. Alas ! he had answered to the roll-call above before the pension came, but I was able, out of my funds, to allow him 10s a week some weeks before his death, and to give his mother a little help in her time of need. One of England’s true hearted sons has passed away in Stoker Lynch.”

![]()

Stoker Lynch Laid to Rest February 1899

The following was an English press report concerning the funeral of Stoker Lynch which took place in Kinsalebeg Church on 3rd February 1899. He received full military honours and thirty coastguards from the surrounding area formed a guard of honour and fired three volleys over the grave. There was a large attendance from the local population.

The following inscription was on his coffin:

“Edward Lynch, stoker, Royal Navy, aged 26 years. Died 1st Feb., 1899. R.I.P.”

Reports at the time indicated that the Admiralty were planning to erect a suitable monument over the grave of Stoker Lynch in Kinsalebeg Church but this never transpired. The political situation in Ireland deteriorated in the following years and probably dictated a change in plans for a memorial. The following are more detailed reports on the funeral:

“When the news reached England that Stoker Lynch had died at Monatrea, Co Waterford, the Admiralty telephoned immediately to the Commander-in-Chief at Devonport, directing arrangements to be made for a funeral with full military honours for the late Stoker Lynch. Firing parties of marines and bluejackets, with a mourning party of stokers, were provided for the guardship Howe and the training-ship Black Prince at Queenstown. The order, although without precedent, was received with general satisfaction throughout the naval service. Patrick Lynch, a brother of the deceased, and a stoker serving at the general depot, Devonport, was granted a week’s leave to attend the funeral, which took place at Youghal [Kinsalebeg]. The suggestion to raise a memorial to Stoker Lynch has been heartily taken up by the men in the Devonport Naval command, especially by the Irish contingent, which numbers quite one thousand. Some men have volunteered to give a month’s pay.”

The Irish News section of the New Zealand tablet reported on the funeral as follows:

Waterford – Brave Stoker Lynch: “On February 3rd the remains of Stoker Edward Lynch, Albert Medallist, who died at Monatrea, County Waterford, were interred with naval honours at Kinsalebeg churchyard, two miles from his residence. About 30 coast-guards from Youghal, Knockadoon, Helvic, and Ballycourty stations, in full uniform, under the command of Divisional Officer Lieutenant Dillon, Youghal, and Chief Officer Feast, Youghal station, attended the obsequies. The public were largely represented, and a posse of police under Head Constable Tierney was present from Youghal. At the cemetery a volley was fired by the coast-guards, after which the coffin was lowered into the grave.”

The following report on the funeral appeared in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle on 11th February 1899:

“On Friday afternoon the remains of Stoker Edward Lynch, Albert Medallist of the 1st class, who died at Monatrea, Co Waterford Ireland, were buried with Naval honours at Kinsalebeg churchyard, two miles from his home. The funeral procession started at three o’clock and the internment took place before four. Thirty Coastguardsmen from Youghal, Knockadoon, Helvic, and Ballycourty stations, in full uniform, under command of the divisional officer Lieut. Dillon, R.N., and Chief Officer Feast, attended having received instructions from the Admiralty to accord the deceased all Naval funeral honours. The oak coffin was borne on a bier, covered with the Union Jack, and was followed by the Coastguards. After these came the general public, who attended in large numbers. A body of the Royal Irish Constabulary, under Head Constable Tierney, was also present from Youghal to pay respect to Stoker Lynch’s memory on behalf of the Royal Irish Constabulary Force. Three volleys were fired by the Coastguardsman over the grave. The inscription on the coffin was: “Edward Lynch, stoker, Royal Navy, aged 26 years. Died 1st Feb., 1899. R.I.P.” The deceased hero’s brother, Stoker Patrick Lynch, of H.M.S Vivid, was present at the funeral, having arrived on special leave from Devonport. The mother and the five sisters of the deceased stoker were also present.”

The report continues with the following note:

“Following closely on the internment of Stoker Lynch, his mother has received an official communication from the Secretary to the Admiralty, expressing to her the condolence of the lords of the Admiralty and Royal Navy on the sad demise of her gallant son, with an intimation that the heroic deed which cost his life will not be suffered to become forgotten. It is surmised that the Admiralty authorities have in contemplation erection on Lynch’s grave of a monument of appropriate design to adequately commemorate his deed of conspicuous bravery.”

The report concludes with an overview of the Thrasher incident and the following comment:

“Whilst under treatment he maintained the bearing of a man of high courage, with little thought of self. Patients in hospital for burns generally scream before the surgeon arrives at the bedside, their dread of the pain is so great; this man has never murmured, and when in the greatest pain preferred to suffer the whole of it in order that his comrade might have full attention.”

In the same newspaper, and indeed in other newspapers, there were several letters submitted to the editors relating to Stoker Lynch and to the fund that had been set up to establish a permanent memorial to Stoker Lynch in Portsmouth. Within two weeks of the establishment of the Stoker Lynch memorial fund almost 60 pounds sterling had been raised from a variety of sources ranging from individuals to staff of naval vessels. The fund went on to eventually raise over 260 pounds. The following are some sample letters:

(1) “ Sir, - Please allow me, through the columns of your influential paper, to suggest that we in Portsmouth should do something to perpetuate the name and the heroism of Stoker Lynch. Surely he was “a man of distinguished intrepidity.” It costs, I believe £20 to endow a cabin at the Royal Sailors’ Home. I would gladly share the honour of being one of 50 or 25 to do this. Your obedient servant, An Admirer of Naval Men.”

(2) Letter from Ex-Mayor of Portsmouth “Dear Sir, - I consider it very appropriate that in a Naval town like Portsmouth something should be done to bear testimony of appreciation of such an heroic deed as that performed by the late Stoker Lynch. I think we might do even more to perpetuate the memory of such a deed, of which we should all be proud, but at the same time I think the present suggestion an excellent one, and accordingly have much pleasure in contributing. I should be pleased to contribute more if something further is done. Yours sincerely, H. Kimber.”

(3) “Sir, - It is very good of you to devote the influence of your paper to the local perpetuation of the name of the late Stoker Lynch. Might I suggest that the name of the cabin should be known as either “The Brave” or “Heroic” Lynch cabin ? It would, I think, tend to a more lasting recognition of the man and his deed. I enclose £1 towards the object, and would further venture to suggest that should there be more money subscribed than needed for the cabin the balance should be given to Lynch’s aged mother. This might induce some others, particularly Naval men, to subscribe. I am, sir, Yours &c, J.H. Heffernan”

According to the death notice in the Boston Evening Transcript of 6th Feb 1899 it was the intention of the British Navy to name the next new destroyer after Stoker Lynch but there is no record of the launch of any ship called HMS Lynch.

![]()

Visit to Home of Lynch Family Monatray in April 1899

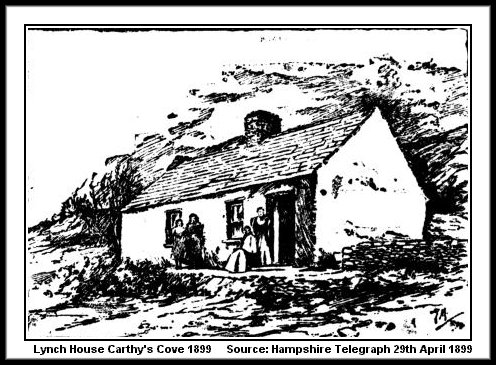

Mr Brymer, a reporter from the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle, visited the Lynch family in Monatray Co Waterford in April 1899 and wrote an extensive report on the visit and the subsequent meeting of the memorial fund contributors. The article was published in the newspaper on the 29th April 1899. It gives extensive details of the family circumstances and an overview of plans for allocation of the money which had been raised in Portsmouth. His description of the trip is somewhat over dramatic and sounds like a journey into the old Wild West with an expectation that a marauding band of Apaches from Monatray would at any instant come charging over the hill. His account of the nine mile jaunting car trip from Youghal to Monatray, rather than use the shorter and more convenient ferry to Ferrypoint, makes one wonder if this representative was on a mileage allowance. His description of being “driven over very rough roads through a bleak, hilly country” does little justice to what is a very scenic part of the country, albeit we are referring to an event which took place over a century ago. Anyway the cause was good so we should not be too critical of the report. The newspaper report was as follows:

Headings: A Hero’s Mother: Life Pension for Mrs. Lynch

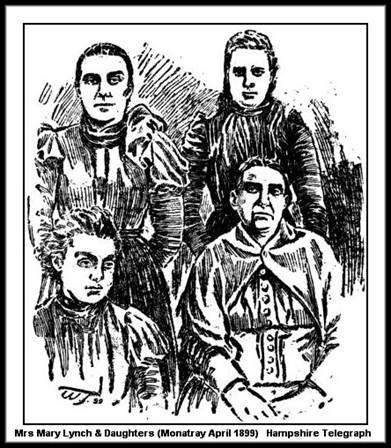

“Away in southern Ireland, in a small cottage in one of the primitive villages, lives a poor widow, whose heart to-day is full of gratitude for an un-expected piece of good fortune – a windfall, in fact, which amounts to nothing less than the bestowal upon her of enough money to keep her from want for the rest of her days. The widow is Mary Lynch, whose portrait, with that of three daughters, and her home, appears below, and the pension is the recognition, largely by Naval people, of one of the finest deeds of self-sacrificing courage recorded in the annals of the British sea-service – the rescue of a shipmate by Stoker Lynch, the widow’s son, in the explosion on the Thrasher. “

“Mrs. Lynch lives in a small village named Monatrea, not many miles distant from Youghal, County Waterford, and it was there she was sought out a few days ago by a representative of this paper, who was charged with the duty of ascertaining her circumstances and her wishes as to the disposal of the money. The journey being for a charitable object, we had written to the London and South-Western Railway Company, the Great Western, and the Cork Stam Packet Company, all of whom very generously granted free passes by way of Milford to Cork.”

“Monatrea is five miles from Youghal as the crow flies, but the estuary of the Blackwater has to be crossed, necessitating a journey by road of nine miles. Our representative chartered a jaunting-car at Youghal, and was driven over very rough roads through a bleak, hilly country till he arrived at a collection of a dozen or so of very scattered thatched cottages, with one or two slate-roofed ones, perched on the side of a steep hill. This was Monatrea, and the jarvey pointed out Widow Lynch’s cottage, which was reached by means of a narrow, rocky path.”

“Widow Lynch and two of her daughters were seated outside, enjoying the afternoon sun. It is almost needless to say that when our representative explained his business, both the widow and her daughters expressed great delight at the idea of so much money being contributed (Note – the amount of money finally raised is not indicated but is likely to have been much larger than the amount of £58 raised in February). The visitor was cordially invited to enter the cottage, and when he stepped inside the little dwelling he wondered however a family, consisting of two sons and four daughters, in addition to the mother and father, who died eleven years ago, could ever have found room to live there. There were two very small rooms and the floor was the bare rock, not levelled in any way. From the rock, too, were hewn the stones used to build the cottage. The windows were very small and the fire had no grate. To get draught there was a wheel with a handle at the side of the chimney, and this wheel was turned smartly, and set a small blast in motion, the same as is done in a blacksmith’s forge.”

“When Mrs Lynch was asked what she wanted to be done with the money, she said she would leave the matter in the hands of those who had so generously subscribed it, all she wanted being something to live upon, and at her death the balance to be equally divided amongst her daughters. The sons, she explained, could shift for themselves. Mrs Lynch, our representative learned, is 62 years of age. She has two sons, both in the Navy, and four daughters, one of whom is in service. The daughters are grown up, with the exception of the youngest, who is only 13 years old.“

The following drawing of Mrs Mary Lynch, mother of Stoker Lynch, and three of her daughters was included in the Hampshire Telegraph newspaper article in 1899.

“Leaving Mrs Lynch and her daughters our representative drove another five miles, to see Father Long, the parish priest of Clashmore, who knew not only Mrs Lynch, but her father and mother. Next day our representative saw Lieutenant Dillon, R.N, Divisional Officer of H.M. Coastguard at Youghal, and also Chief Constable Kearney, of the Youghal Division of the Irish Constabulary. Finally, an agreement was drawn up and signed by Mrs Lynch, and our representative left for England, the next step being to call a meeting of the subscribers to the fund, and obtain their sanction to the arrangement provisionally agreed upon.”

![]()

Meeting of the Subscribers to Stoker Lynch Memorial Fund

A report of this meeting was also printed in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle on 29th April 1899. The Stoker Lynch Fund had reached two hundred and sixty two pound sterling at this stage which was a substantial amount of money at the time. The first part of the plan was to endow a cabin at the Royal Sailors’ Home in Portsmouth in honour of Stoker Lynch and this would cost £20. The bulk of the remaining money was to be in a form of pension to Stoker Lynch’s widowed mother and the Lynch family. Fr Long, the pragmatic Parish Priest in Kinsalebeg/Clashmore, suggested that the proposed pension of ten shillings a week should be reduced to five shillings a week as the Lynchs were a long lived family and in any case he believed that five shillings a week would go a long way in Monatray. A cheque for one pound was to be sent to Mrs Lynch every four weeks and the Bank of Ireland in Youghal had agreed to cash the cheque without charging commission, an unusual event which was never likely to be repeated after this single occurrence in 1899!. The report contains a detailed description of the discussions regarding the fund raising and distribution of the funds. It is obvious from the discussions that the bravery and early death of Stoker Lynch had created an enormous swell of support in England. The Evening News and Hampshire Telegraph played a crucial role in raising public awareness and also in the collection of subscriptions. The meeting report went as follows:

“This gathering took place on Wednesday evening in the Mayor’s Parlour at the Town Hall, his Worship, Alderman T. Scott Foster, presiding. The ex-mayor was unavoidably absent. The Mayor in opening the proceedings, said that the appeal by the Editor of the Evening News and the Hampshire Telegraph had resulted so satisfactorily. It must have been pleasing to the paper, and they must all feel that the matter was ably taken up, while the mother and sisters of the heroic stoker, Edward Lynch, must certainly feel most grateful that the journals had taken such a great deal of trouble with the matter.”

“The Proposed Pension: Mr Brymer then gave an account of his visit to Ireland, and the result. He explained that when the subscription-list for the “Stoker Lynch Fund” was first opened in the Evening News and Hampshire Telegraph, the intention was to endow a cabin at the Royal Sailors’ Home, Portsea, which would cost £20. As the amount received was far in excess of the sum required, and subscriptions kept coming in, it was decided that the money, after the cabin was endowed, should be handed over to Lynch’s widowed mother. He was pleased to say that the response to the appeals in the News and the Hampshire Telegraph had been so generous that the fund now amounted to £262 7s (Applause). [Note: Around 30,000 euro in year 2011 terms]. When the amount had reached £200 they communicated with Chief Constable Kearney and Lieut. Dillon, and this led to his paying a visit to Ireland to ascertain the best way to assist Mrs Lynch and to learn her wishes. Mrs Lynch at first agreed to a proposal that she should receive ten shillings a week, but when he afterwards saw Father Long, of Clashmore, that gentleman pointed out that Mrs Lynch came of a long-lived family, both her father and mother living till they were between 85 and 90 years of age, and there was every probability of Mrs Lynch living till she reached that age. At 10 shillings a week the fund would last 13 years, and what would become of the widow then?. Father Long suggested 5 shillings a week would be better. That seemed a small sum, but Father Long stated that many a family in that locality was brought up on less than 10s. a week and with 5s. a week the money would last as long as Mrs Lynch lived, and she would not be dependant on outside relief, as she only paid £1 a year for the cottage and garden, and could eke out a small sum by keeping fowls and a pig. Besides, this 5 shillings a week would go a long way in the locality, and one of Mrs Lynch’s sons allowed her a portion of his pay.”

“Terms of the Agreement: The suggestion was heartily approved by Lieut. Dillon and Chief Constable, and Mrs Lynch jumped at the idea. It was a great consolation, she said, that she would have 5s. a week coming for life, and that what was left would go to her four daughters. An agreement was then drawn up, which Mrs Lynch signed. Mr Brymer read this agreement, which provides for the deposit of the money at the Capital and Counties bank, Landport, in the names of the Mayor of Portsmouth and the Directors of the Evening news and Hampshire Telegraph Company, and for its payment to Mrs Lynch at the rate of 5s. per week. In the event of Mrs Lynch dying before the money is expended, the balance is to be equally divided between the four daughters, but this is only after the youngest daughter, now 13, has attained full age. In the event of the youngest daughter being under age at her mother’s death, the instalments are to be paid to her till she attains her majority, when her sisters will share and share alike. Mr Brymer added that Mr Hellyer, manager of the Capital and Counties Bank, Landport, had agreed to take the money at interest and allow cheques to be drawn against it. A cheque for £1 would be sent Mrs Lynch every four weeks, and would be cashed at the Youghal branch of the Bank of Ireland without any commission being paid (Applause).”

“Unanimously Agreement: Mr Harry Hall proposed the ratification of the agreement made by Mr Brymer, and said he had watched the progress of the fund in the Evening news with the greatest interest, and all the subscribers must be very pleased at the success. Mr T. Lovatt as secretary of the Naval Firemen’s Society, which had contributed largely to the fund, seconded the proposal, and said it was very gratifying to Naval people to see the way in which the Evening News had initiated such a grand fund and carried it to such a successful issue (Hear, hear !). Mr C.H. Fowler congratulated those connected with the Service on the generous way in which they had contributed to the fund. It was a long time ago, he said, that he had the happy thought to suggest the starting of the fund, and wrote to the Evening news. By the way in which the News appealed for help they carried out their part in a most satisfactory manner, and everyone owed them very many thanks. At one time the fund looked to be languishing, but a letter from Dr Doyle, and another, with a subscription, from the Mayor, helped the fund considerably. He was very gratified to be present. The proposition was carried unanimously.”

“Thanks to the “News” and “Telegraph”: Mr J.H Heffernan R.N then proposed a vote of thanks to the Evening News and Hampshire Telegraph for having initiated the fund and carried it through with such good taste and tact. The success of the fund was creditable reflection on the Evening news, whose efforts in carrying the matter through were deserving of every thanks (Applause). Dr Fowler had very great pleasure in seconding, and added that the News very generously contributed to the fund. Mr Lovatt, in supporting, took the opportunity of heartily acknowledging the valuable services of Mr H. Bell, the cashier of the Evening News (Applause). The resolution was carried unanimously, and Mr W.R. Fowler next moved a vote of thanks to the Mayor for his valuable services, Mr Harry Hall seconded, and the proposition having been duly passed, the Mayor’s brief acknowledgement brought a very pleasant meeting to a close.”

![]()

Poems & Songs of Stoker Lynch

A number of poems and songs concerning the bravery of Stoker Lynch were written over the years since 1897. We record here the words of two of these which we came across in our travels.

Poem of An Irish Hero Stoker Lynch:

| Poem of An Irish Hero Stoker Lynch |

| Torpedo destroyer they called her, but alack, |

| Destroyed herself and wrecked with broken back, |

| On the old Dodman rock she lay |

| First land you meet across the stormy bay, |

| When from the "Straits" you make your homeward way. |

| … |

| And in the impact of that first and sudden shock, |

| Which left her stranded on the Dodman rock, |

| Burst from her pipes the scalding and the scathing steam. |

| Blinded, bewildered, like to men that dream, |

| The stokers shut into their death-trap seem. |

| … |

| And one alone - their chief - has reached the waveswept deck, |

| And left his comrades in that awful scene of wreck. |

| Oh, blame him not to fly that cruel and that tortured death. |

| Sweet to his parched throat to breathe once more the heaven's breath, |

| But stoker Lynch he too might free him from that hell beneath. |

| … |

| Swift to his mind there comes the thought of stoker Paull. |

| Less light of limb than he, who must unaided fall. |

| Forsake his messmate to such fate and go ! |

| Safe from the stricken engine-room, and scenes of woe ! |

| Perish the thought, his hero's heart said - No |

| … |

| To drag an unconscious weight e'en but a fathoms length, |

| It seemed just then a task for more than human strength , |

| All else were dead or dying in the fierce steam-blast. |

| God aid his flagging limbs, the hatchway's reached at last |

| And on the deck, alive. No more, his precious burdens cast. |

| … |

| In days of Ancient Rome the mural crown was given they say |

| To him who first the rampart crossed in deadly fray, |

| And valour's cross doth many a soldier now obtain, |

| But none for deed more gallant than the hero of this strain |

| Wrought by a tortured man himself beset by agonizing pain. |

| … |

The following song about Stoker Lynch written by Sidney T. Stephens appeared in the Naval and Military Record but there is no indication of how the song is sung. There are a few variations of the song – in some versions the third line of the first verse (“Sung by the ...”) is missing and the second verse is missing completely in some versions.

The Song of Stoker Lynch:

| The Song of Stoker Lynch |

| This is the song of the Thrasher, sung from the South to North, |

| Over the wind-swept ocean, wherever the flag blows forth. |

| Sung by the First Lieutenant, sung by the Engineer |

| The song of a plain bluejacket, of those who never flinch, |

| Written in gilded letters – the song of Stoker Lynch. |

| … |

| He wasn’t an earthly angel, he was like most you meet, |

| There was often a headwind blowing as he tacked down Union-street. |

| He knew the colour of paintwork, he’d oft seen the jaunty’s eye |

| Fixed in a fatherly manner that nearly makes one cry. |

| But still the ditty is chorused, read by the furnace gleam |

| Sung to the throb of the engines, the music of hissing steam. |

| … |

| Thick was the fog in the Channel, thicker it lay on the land |

| You couldn’t see the jackstaff forward, you could scarcely see your hand. |

| The Dodman stood out in the blackness, the boats came up from the West, |

| And there, for a pall the fogdrift, some went to their last long rest. |

| The Thrasher, the flagship, leading, was first the danger to learn, |

| Quick as the telegraphs ringing, the links crashed over astern. |

| … |

| No time for closing the throttles, no time to think, but to do, |

| The engineer drove those engines – he drove them for all he knew. |

| But quick as the links went over, they had hardly eased her speed; |

| She bumped with a ripping and tearing, she took to the rocks indeed. |

| Lord ! what a scrunching and crashing as she tore her bottom first, |

| Then what a hissing and screeching as the forward steampipe burst. |

| … |

| Some thought of their homes and mothers, some thought what only they knew; |

| Some thought of their wives and sweethearts, he thought of his pal below. |

| Down in the forrard stokehole, choking, with gasping breaths, |

| Was Paull on the iron ladder, standing between two deaths. |

| Below him the rising water, above the scalding steam, |

| Five feet of pain and burning, and then the daylight’s gleam. |

| … |

| But he couldn’t force the passage, till a head and arm came through, |

| Down through those feet of torture, down through that devil’s brew. |

| A grip on his reeking collar, a pull, a sharp hot pain, |

| Then he came up through the hatchway gasping to breathe again. |

| It was Lynch who bridged the steam cloud, ‘twas he the danger braved, |

| But he paid the price of courage when his pal’s life he saved. |

| … |

| He lingered on a long time, ‘twas mercy when death came |

| To the roll of British heroes added Stoker Lynch’s name. |

| … |

| That is the song of the Thrasher, sung from the South to North, |

| Over the wind-swept oceans, wherever the flag blows forth. |

| The song of a plain bluejacket, of those who never flinch, |

| Written in gilded letters – the song of Stoker Lynch. |

![]()

Summary

We have outlined elsewhere in this history the many Kinsalebeg men who served in the British navy in the period up to and including the 1st World War. A number of these died in naval service and many returned to what were no doubt difficult times leading up to the Irish War of Independence. The political climate would have changed considerably in the intervening years and there is no doubt that any association with the British military forces in this period was viewed with suspicion in many quarters despite the long established tradition of Irishmen serving in the British navy and army. The 1st World War, the Irish War of Independence and the subsequent Irish Civil War were major events in the 1st quarter of the 20th century. The complicated series of events and political changes in this period led to the lives, exploits and indeed deaths of many Irishmen serving in British forces being overlooked and subsequently forgotten in later years. Edward “Stoker” Lynch was without doubt a Kinsalebeg hero who deserves to be remembered in his native land for his outstanding bravery.

![]()

Appendix A

Accident Report from Belfast News Letter on 30th Sept 1897

The following report on the HMS Thrasher accident was reported in the Belfast News Letter on 30th September 1897:

Headings: Torpedo Boat Destroyers Ashore: The Lynx and Thrasher Wrecked: Explosion on the Thrasher: Four Men Killed and One Injured.

The Lynx and Thrasher, torpedo boat destroyers, are both ashore at Dodman’s Point, a rocky and dangerous spot, ten miles east of Falmouth. The news reached Devonport yesterday afternoon, and the Traveller, an ocean tug, is held in readiness at Devonport to go to their assistance. The sea in the channel is calm, but the weather is very wet and foggy. The two vessels were out on an instructional run from Plymouth, and it is presumed they went ashore during the heavy fog of this morning. Naval officials at Devonport are reticent, but a conference is now proceeding between Sir Edmund Fremantle, naval commander-in-chief; Flag-Captain Johnstone, and the other members of the staff.

A Falmouth correspondent telegraphs that the crew of one vessel is safe. The Thrasher has almost broken in two, and the Lynx is hanging in the middle. The two vessels, together with the Sunfish, left St. Ives yesterday morning, and lost each other during the fog. The Sunfish, fortunately, cleared the Dodman, but had a narrow escape.

The Press Association’s Plymouth correspondent, telegraphing later last night, says – A message received here from Mevagissey states that three men named Hannaford, Kennedy, and Nicholls, stokers of the Lynx and Thrasher, have been killed by the explosion of a steam pipe; and two other men named Paul and Lynch have been landed seriously injured at Gorran Haven. Gorran is some miles from St. Austell, the nearest railway station, and owing to the difficulty in obtaining definite information from naval authorities at Devonport Pressmen from Plymouth have gone to the scene of the disaster. It was reported this afternoon that one of the destroyers had broken her back, but this is as yet not confirmed, though there is no doubt both vessels have been seriously injured. The Thrasher, which was in collision with the cruiser Phaeton a short time ago, just after they had started for the Pacific station, was attached, after her defects had been made good, to the Devonport flotilla for instructional purposes. The boats left Devonport on Monday for the usual four days’ exercises, making Fowey their headquarters, and they were together this morning off the Dodman – the cape which stands out prominently on the coast between Fowey and Falmouth. The weather had been very bad, and during a thick fog, under circumstances as yet unexplained, they both went ashore. A Fowey correspondent wired, in answer to an inquiry – “Rumour is confirmed; Lynx and Thrasher are ashore at Dodman Point. Some of the crew are injured, and outlook is very serious. Assistance is at hand”. As soon as telegraphic communication could be obtained the information was conveyed to the naval commander-in-chief at Devonport, but the details were of a meagre character. Directly Admiral Sir E. Fremantle was acquainted with the occurrence, he made preparations for sending assistance to the two stranded vessels. In the first place, a telegraph was sent to Falmouth giving instructions to the tugboat Aetna, which had towed down a lighter. The next orders were given at Devonport for the tug Trusty to proceed down the coast immediately; and the Spider, the instructional vessel attached to the Royal Navy Engineers’ College at Keyham, was also requisitioned together with the Traveller, an ocean tug. A working party from the Royal Navy barracks was also sent. All haste was made in the preparation at Keyham and Devonport. A correspondent at Movagissey telegraphed this afternoon – “The mishap to the two destroyers was very serious, indeed. Three men were killed, and two severely injured, both of the latter being landed at Gorran Haven. The crews were taken off by a Mevagissey fishing lugger, which went to their assistance. One vessel was almost broken in two, and the other seriously damaged”. From this it does not appear whether the accident was due to a collision, the boats being then run aground in order to save them from sinking, or whether they went ashore in the fog, as was first reported. Unusual steps have been taken to ensure a large attendance of naval medical officers at the spot, and this afternoon Dr. Clift, of Devonport Dockyard, with a surgery attendant, was despatched by a special tug to Gorran, taking with him a quantity of medical appliances, such as cotton wool and oil, presumably evidence at least that there were numerous cases of scalding. The cruiser Pelorus and the torpedo gunboat Sharpshooter are out on their trials, but a signal awaits them at the breakwater fort, directing them to proceed to a spot off Gorran with all despatch, and land their medical officers. Staff-Captain Osborne, of Devonport Dockyard, had also proceeded in a tug to Gorran, and, having regard to his wide experience, it is assumed in naval circles he will direct any salvage operations. The Curlew, gunboat, tender to the Cambridge, is held in readiness to tow lighters with provisions for the men engaged at the scene of operations, and the naval commander-in-chief has given orders that the whole of the available docks at Devonport and Keyham are to be pumped out, and that workmen are to stand by all night, with a view of docking either of the damaged craft should they be conveyed to Devonport during the night. It is understood that every effort will be made to bring both vessels to Devonport, and, as the sea is very calm and the fog has cleared, this operation should present no insurmountable difficulty.

In a later despatch the Press Association’s Plymouth correspondent says he received the following official communication, timed half-past eleven, from Admiral Sir Edmond Fremantle:- “The commander-in-chief deeply regrets that he has received information that the following men were killed or injured on board the Thrasher by the explosion of a steam-pipe: Killed – 16,866 leading stoker, second class, John Hannaford; 158300, Stoker William Nicholls; 148,774, Stoker Michael Kennedy. Injured:- Stoker James H Paul, Stoker Edward Lynch.” The commander-in-chief adds – “It is believed this disaster occurred while the Thrasher and Lynx were ashore off Dodman Point in a dense fog to-day. Both vessels have since been got afloat, the Thrasher having proceeded to Falmouth, and the Lynx, in which no one has been hurt, has returned to Devonport. The injured are receiving medical attention on shore, presumably at Mevagissey. “