History of Kinsalebeg

Ferrypoint

Preface

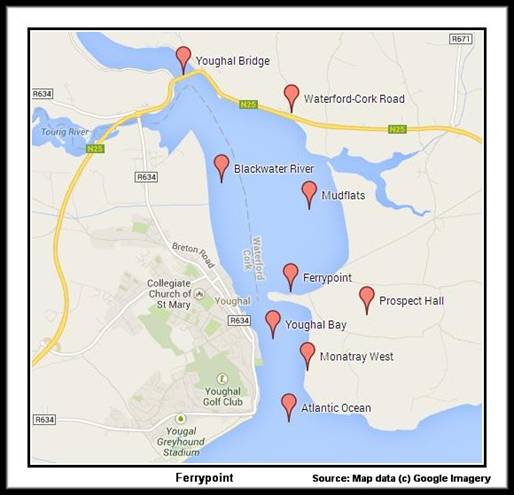

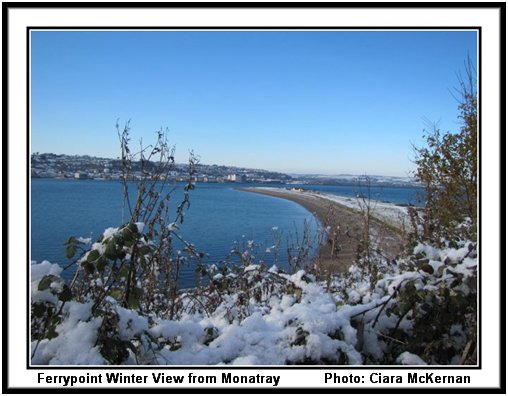

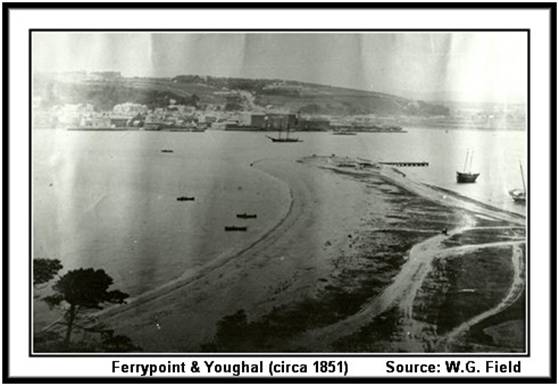

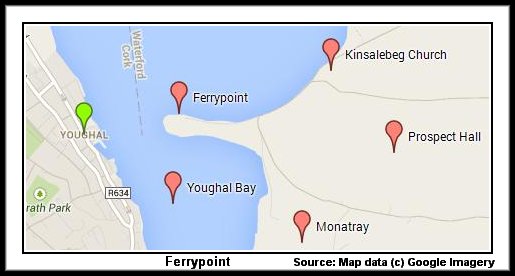

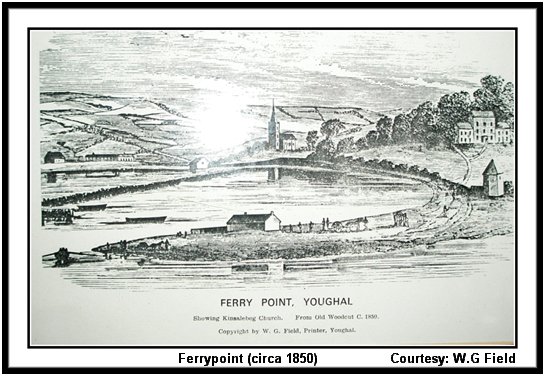

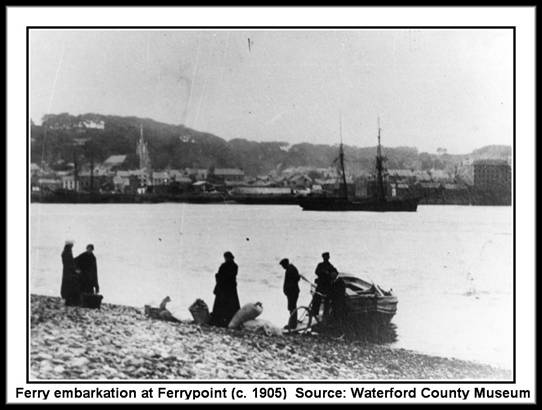

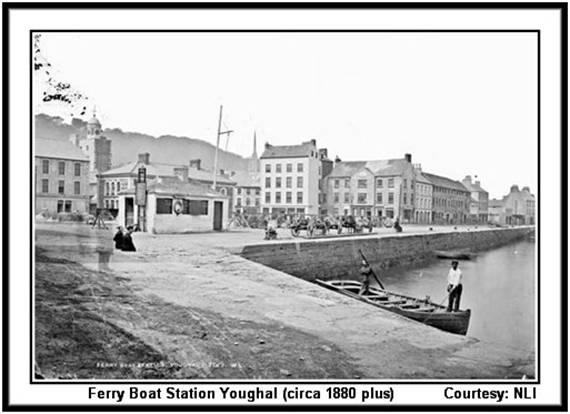

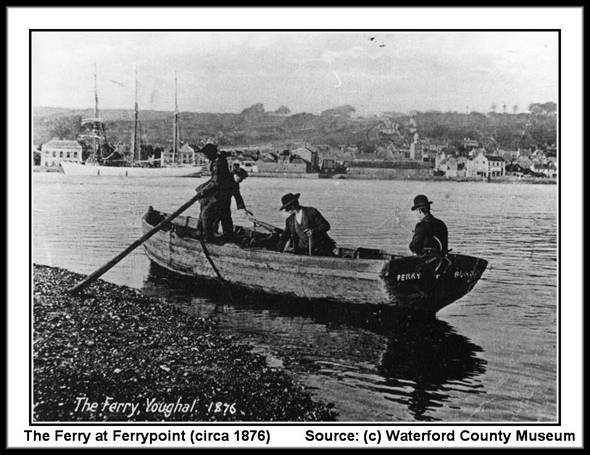

Ferrypoint is an unusual spit of land which extends out from Monatray into Youghal Bay. For around seven hundred years it was best known as the landing point for the Youghal to Ferrypoint ferry. When viewed from Monatray Hill, Ferrypoint looks like a finger pointing towards Youghal, in the neighbouring county of Cork, warning the inhabitants that we are “keeping an eye on you” and that any further indiscretions could have dire consequences! Ferrypoint is in effect a sand and shingle bar stretching out about 800 metres in the direction of Youghal with the Atlantic Ocean lapping the steep shingle beach on the southside and the River Blackwater to the north. The tip of Ferrypoint is a short four hundred metres from Youghal and through this narrow channel races the River Blackwater as it makes its entrance into Youghal Bay. It is across this narrow channel that the Youghal to Ferrypoint ferry journeyed on a daily basis for around seven hundred years from the 13th century to the 1960s. The ferry was the primary transport link between the southern parts of the counties of Waterford and Cork until the building of Youghal Bridge in the early 19th century. This is a dangerous stretch of water and has been the scene of many boating accidents down the years as we will outline later.

Ferrypoint itself is very exposed to the elements and suffered in severe weather conditions particularly when Atlantic storms raged in from the south accompanied by mountainous waves. The Hyde family lived in a cottage which was precariously located on the tip of Ferrypoint and surrounded on three sides by water. The Hyde house was seriously exposed to weather conditions and high tides. The Lehanes lived in a house overlooking Ferrypoint and after a stormy winter’s night we would look anxiously across Ferrypoint for signs of life. It would not have surprised us in the least to see the Hyde cottage floating around the bay with John & Cathy Hyde and family clinging precariously to the chimney but thankfully we were spared the excitement! To the north of Ferrypoint towards Pillpark and Youghal Bridge lies an area of mudflats which is a feeding area and full tide roost for many of the birds that winter around the bay. This is the seasonal home of many species of birds including the Little Egret, Black-Tailed Godwit, Wigeon, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Curlew, Redshank and other varieties of wading birds. There are also smaller numbers of wintering birds such as the Pintail, Gadwall, Sanderling, Spotted Redshank, Little Stint, Spoonbill, Shoveler, Curlew Sandpiper and Scaup. A number of scarce birds have been sighted in this area over the years including a Baird’s Sandpiper and a Ring-billed Gull.

Youghal Bay, and surrounding areas like Ferrypoint, Caliso Bay and Whiting Bay, are very popular fishing areas for a variety of fish including bass, pollack, mackerel, conger, dogfish, flounder, plaice and dabs. The Blackwater River is of one of the premier salmon fishing rivers in Ireland and the salmon fishing rights are largely controlled by the Duke of Devonshire who has the unusual right of apparently owning the rights to the river bed itself as well as the fishing rights on the river. Up to the 1950s there would often be up to thirty salmon yawls, using drift nets, fishing around Youghal Bay from Clashmore to the outer bay area and also further down the Waterford coast towards Ardmore. This industry went into severe decline from the 1950s onwards primarily due to diminishing salmon numbers. This form of salmon fishing was carried out in four man fishing boats known as yawls which were unique to this area. The boats dotted the Blackwater estuary and the bay from February to summer with their drift fishing nets bobbing in their wake. A number of Kinsalebeg families including the Moylans, Mahonys, Powers, Hydes, Roches, Lynches, Cashmans and Hartys were involved in yawl drift net salmon fishing over many generations in this area. Our own fishing experiences at Ferrypoint were largely confined to mackerel fishing during the summer months and the combination of fresh mackerel and early morning mushrooms was a tasty meal and the nearest we got to haute cuisine growing up in Monatray.

The central grassy area of Ferrypoint was the sea-level summer training base for Kinsalebeg footballers, hurlers and camogie players in the nineteen fifties and sixties. It was a picturesque location to play sport with the backdrop of the hill of Monatray to the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the south. On the northern side the Blackwater River completed the final mile of its journey from Youghal Bridge into the Atlantic Ocean and parallel to the river were the mudflats with their flocks of wintering birds. Across Youghal Bay to the west of Ferrypoint was the picturesque town of Youghal which played a large role in the history of Kinsalebeg. The gradual encroachment of the shingle beach brought an end to the sporting activities on Ferrypoint and indeed other former activities such as Macra na Feirme field days. Ferrypoint was generally not used for playing competitive GAA matches as the dimensions were too small but it did not prevent the playing of some competitive “friendly” training games between the locals. The surface was fairly diabolical with a mixture of stones, sand and a thick wiry type of grass that resisted the efforts of the strongest camán wielders. The Atlantic Ocean encroaching at high-tide on one side and the ever present Tráigín lake in the middle of Ferrypoint were awaiting traps for any wayward shots.

At times Ferrypoint was used to play camogie matches involving the local Kinsalebeg team under the genial management of story-telling bachelor Barry Harty. Barry was well into pension age when he took up the mantle of manager of the camogie team but had not yet ruled out the possibility of ending his bachelor days. One of the camogie matches played on Ferrypoint in the 1960s was between Youghal and Kinsalebeg. The Youghal team travelled across via the ferry and were fully togged out when they arrived in Ferrypoint. This was just as well as changing facilities at Ferrypoint were still at the planning stage but it was nevertheless somewhat of a disappointment to the local lads! The Kinsalebeg camogie team was drawn from a number of families including the Barrons, Dalys, Hickeys, Lehanes, Connors, Healys, O’Neills, Lynches, Flynns, Hydes, Sewards, Hallahans, Hallorans and O’Briens. The Kinsalebeg team that togged out that evening against Youghal was a formidable physical outfit and had in its ranks a number of talented camogie players including Mary Barron, who later went on to play camogie for Cork, and Nonie Healy who played for Waterford. The physically imposing Kinsalebeg team was in stark contrast to the Youghal girls, who appeared to be of a more delicate disposition. Their pale skin and slight frames seemed altogether more suited to the cast of the Bolshoi Ballet than a local camogie derby. Barry Harty put a strong emphasis on winning the physical battle before getting involved in any kind of fancy camogie. His motto would have been very much in the line of “if its higher than a daisy and it is moving then hit it!” The match took a predictable route with the early fine touches of the Youghal girls being gradually worn down by the sheer physical intensity of the Kinsalebeg ladies. A suitably chastened Youghal team departed on the return ferry to Youghal that evening with both their egos and bodies badly bruised by the encounter.

In the 1960s Ferrypoint was a popular meeting place for people of all ages around Kinsalebeg. They would congregate there most evenings of the week and on Sunday afternoons. The focal point was the Lehane shop at Ferrypoint which was an enterprise largely conceived and driven by my mother Kitty. The shop supplied the usual mix of confectionery, minerals, ice-cream, cigarettes and tobacco. Teas & sandwiches were on the menu provided the living room was not occupied by listeners to the big match on the radio. It is doubtful if there was any high degree of profit from the enterprise as we were probably our own biggest customers. There is little doubt that the ice-cream was a loss leader as we were all at fault for being a tad too flaithiúil with the cutting of the 6 penny wafer. We operated a form of credit or “on tick” as it was called it for anyone who was caught short on any particular day. The customer’s name and amount owing was written on the wall beside the shop counter and as the years went on the accumulated hieroglyphics began to resemble an ancient Egyptian manuscript. The plug of tobacco was a major “on tick” item with the local salmon boat fishermen as their oil skin jackets and indeed their exposure to salt water was not conducive to carrying around cash.

The main activities were the games on Ferrypoint and of course the beach but most people came together just to talk and discuss the major issues of the week. These discussions would continue into the late evening in our house with the stragglers departing well after midnight. The evening discussions were usually wrapped up by Bobby Connery and my father Dan Lehane with a quick synopsis of the key international issues of the day and the high tare rates for beet going into Thurles during the inclement weather. Listening to GAA matches on the wet battery radio was another popular Sunday afternoon activity in the days before televised GAA matches. The living room of the house was regularly full and the overflow would sit on the wall outside the house where they listened through an open window to the match commentary of Michael O’Hehir. My father was an easy going individual and tended not to be fazed by anything – one of his expressions when things went wrong was “let there be little or no panic!” However the wet battery radio was the one thing which could put him on edge on the day of a big match from Thurles or Croke Park. He did not trust the technology and had a nagging concern that the transmission would break down with five minutes to go and the game on a knife edge. Thankfully the technology usually stood up and the listeners could proceed to the, often heated, post match analysis phase.

I won my first donkey derby on Ferrypoint riding Neddy, an eccentric animal belonging to Tommy Roche of Prospect Hall. The donkey derby features in the annual Field Day run by the ever energetic Kinsalebeg Macra na Feirme. I was very familiar with Neddy in his normal working day mode as I used to borrow him to pull a beet setting machine each spring. He was a very dainty and placid animal between the drills and his slow and steady pace was much better suited to beet setting than our own resident farm horse Paddy. Paddy in fairness was also a very placid animal but had a tendency to increase the pace as he approached the headland which resulted in erratic placing of the beet seedlings. However Neddy appeared to have little interest in sport and took a violent objection to attempts to sit on his back. Initial attempts to ride him bareback usually resulted in a bucking and kicking routine with inevitable painful results for the jockey and anyone in the vicinity of his hind legs. After an energetic working session, pulling a harrow around Tommy Roche’s acre, Neddy settled down sufficiently to enable me to get on board and head for the big race in Ferrypoint. We had a fair idea that the main competition would come from Shanahan’s black donkey, ridden by Pat Hickey, who had the advantage of altitude training on the top of Monatray. As expected we were running neck and neck with fifty yards to go but Neddy found another gear as we approached the finish line and pulled ahead. However the sight and sound of the cheering crowd near the finish threw him completely off balance. He wheeled away in a panic and neither God nor man would stop him from heading for the beach and the Atlantic Ocean. My concerns about drowning, due mainly to a chronic inability to swim, were cut short as Neddy deposited me in an embarassing heap on the strand before he headed off into the sunset with a final belligerent kick from the hind legs. Our pride was severely dented but we returned undaunted to Ferrypoint for the return grudge match the following year. In the interim Neddy had apparently overcome his agoraphobia and we duly won the race and the ten shillings that went with it. Anyway we will now have to cease our recollections from the more recent past and attempt to pull together an overview of Ferrypoint over the centuries.

![]()

Introduction

The focus of this historical summary is very much the old history of Ferrypoint. The history is made up primarily of a series of dated events and reports throughout the centuries. As much original material as could be located has been included, with some particularly lengthy newspaper reports being included in their entirety. We have included an extensive amount of material on specific incidents such as the ferry boat accidents as much of this has not been published since the events occurred. The history of Ferrypoint is obviously closely linked to that of its next door neighbour Youghal and in particular the operation of the ferry between the two locations.

![]()

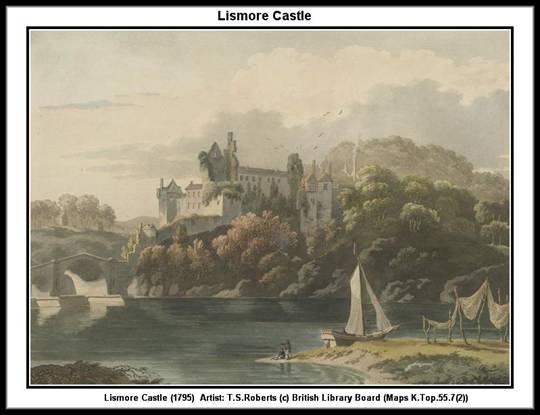

Change of direction of River Blackwater (830 AD)

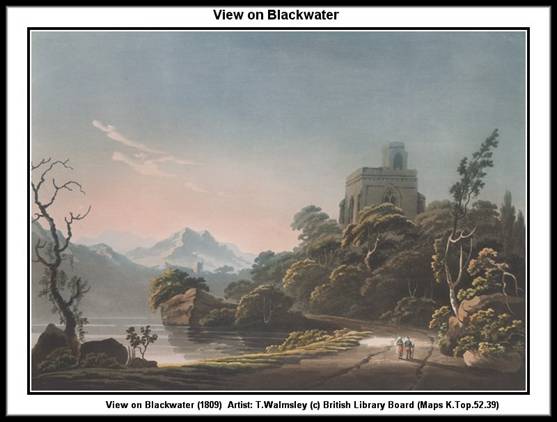

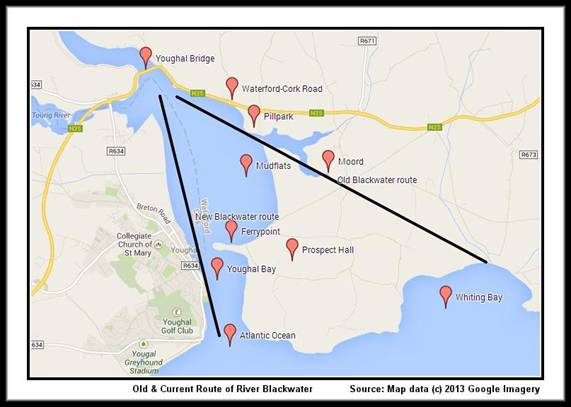

Date March 830 A.D: The River Blackwater is one of the major rivers of Ireland. The latter part of its journey to the sea from Fermoy to Youghal runs mainly through the county of Waterford. The last phase of this journey, from Lismore to Youghal, runs through one of the most scenic parts of Ireland. Both sides of the river from Lismore Castle to Youghal are steeped in history with castles, historic buildings, trees, gardens, the vestiges of large estates and a rich historic heritage. The River Blackwater initially flowed into Whiting Bay and not Youghal Bay. This of course made a tremendous difference to Youghal and was a key factor in the development of the town as a major trading centre from the 12th century onwards. Access to internal markets was crucial to seaport trading towns and the Blackwater provided this hinterland access for Youghal. In a similar fashion the Suir was crucial to Waterford City, the Lee to Cork City, the Liffey to Dublin and the Shannon to numerous towns. According to Keating1 a 17th century historian there was a violent storm in Ireland towards the end of March 830 A.D., which altered the exit of the Blackwater River from Whiting Bay to Ferrypoint. Keating described it as follows:

“there were such terrible shocks of thunder, and the lightning did such execution, that 1010 persons, men and women, were destroyed by it between Corcabaisginn and the sea-side” (2) “By this convulsion of nature the mouth of the Blackwater was changed. Instead of flowing north of the Ferry Point, through the valley that stretches from the creek of Pilltown to Whiting Bay, the river piercing the confining bank of shingle, rushed to meet the ocean through the low-lying ground now forming the harbour of Youghal, and straightaway converted a deep well-planted valley into the arm of the foaming sea. The embouchure at Whiting Bay (still called by the Irish Beal-Abhan, or the Mouth of the River) was gradually closed up, as the river deepened for itself a new and more direct channel by Eo-chaille, or Youghal.”

This violent storm was also responsible for breaking up the island of Inis Fidhe in Skull harbour into the three separate islands of Long Island, Castle Island and Hare Island. It should be noted that the Annals of Clonmacnoise give the apparent date of the storm as the 18th March 801 A.D. (“the horrible, great thunder, the day following the feast of St. Patrick”).

The Historical Annals of Youghal4 gives an overview of the original route of the River Blackwater as follows:

“From a careful geological examination of that portion of the barony of Decies-within-Drum, which lies between Clashmore and the sea, we have come to the following conclusions respecting the ancient course of the Blackwater: At the Broad of Clashmore, where the River Lickey now runs into the Blackwater, a branch of the latter diverged from the main body of the stream, and passing above D’Loughtane (The place of the Lakes) it kept the present bed of the Lickey for a few miles; then heading towards the south about Ballyheeny bridge, it passed its waters into the upper arm now by Ballynatray, Templemichael, and Rhincrew (beneath which it received the Teora), and met the subordinate branch at Pilltown; when the united waters discharged themselves through the lower, or south-eastern, arm of that creek into the ocean at Whiting Bay.”

“The valley between Piltown and Whiting bay, though now reclaimed and cultivated, presents all the marks of alluvial and lacustrine formation. Sand and concrete shells are turned up at low depths, and tradition preserves the memory of some primitive anchors with a single fluke having been found in it.”

“The ancient course of the river is very notable from Templars’ House at Rhincrew, whence the whole gorge or valley from Pilltown to Whiting Bay is seen at once, with the blue waters of the ocean in the distance. Another good prospect may be obtained from the summit of Cork Hill, at the entrance to the barracks. From this place, the Ferry Point is seen to stretch itself over towards the town, reminding us of the period when it actually reached across the present harbour, then a marshy plain. The harbour itself is a blind one. On approaching the town from the south side, by the present mail-coach road to Cork, the county of Waterford seems one with that of Cork, and the East Point appears united with Knoc-a-vauriagh (Knockaverry).”

![]()

Early References to the Ferry at Ferrypoint (1288-1349)

One of the earliest recorded references to the Youghal to Ferrypoint ferry related to the year 1288 when the lease cost of the ferry appeared in what was known as The Calendars of Inquisition Post Mortem11(CIPM). The CIPM details the results of investigations into the property of deceased people to establish what income and legal rights were due to the crown. The CIPM were generally related to the reign of particular monarchs so the Calendar of Inquisition Post Mortem 22 Edward III referred to inquisitions that took place in the 22nd year of the reign of Edward III which commenced in the year 1327 so the actual date was 1349. The early ferry reference appeared in the CIPM of King Edward I for the year 1288 (16th year of his reign) and concerned “the Manor of Inchecoyn [Inchiquin] and Ville de Yochil [Youghal]”. The ferry rights were at that point belonging to the Manor of Inchiquin for which they paid a lease of 40 shillings a year. Relevant abstracts from the CIPM were also recorded in The Historical Annals of Youghal4. The CIPM entry for 1288 which is as follows:

“The ferry of the water del Yochil, 40s yearly”.

Date 1321: Another early entry regarding the lease cost of the ferry appears in the Calendar of Inquisition Post Mortem11 (CIPM) 14 Edward II [Year 1321] and indicates that the lease cost was now 62 shillings and 2 pence per annum. The ferry rights at this point were apparently held jointly by the De Clares and the Friars Minor. Sir Gilbert de Clare had made some arrangement with Gilbert Jentyl presumably for the operation of the ferry. The De Clares owned the Manor of Inchiquin in this period and the manor comprised of land in the vicinity of the Castle of Inchiquin (near Killeagh) together with the town of Youghal and also most of the land of Kinsalebeg including Ferrypoint. We will see elsewhere the rather troublesome period of De Clare involvement in Kinsalebeg when they ran into a lot of inheritance difficulties mainly due to their absence from the area during their period of ownership. They were one of the earlier recorded “absentee landlords”. The entry in CIPM for the year 1321 and abstracted in The Historical Annals of Youghal4 was as follows:

“The Ferry is worth 62s. 2d yearly, out of which Gilbert Jentyl holds yearly during his life, from the grant in fee of Sr. Gilbert de Clare, 22s. 2d., and The Friars Minors hold the remainder through the favour of their owners.”

Date 1349: A third reference to the ferry from the year 1349 [CIPM11 22 Edward III] indicates that the ferry is worth 34 shillings and four pence a year. It also refers to twenty four burgesses in Kinsalebeg (Kynsall) which were part of the Manor of Inchiquin at this point – essentially this means that most if not all of Kinsalebeg was part of the Manor of Inchiquin in 1349. The year 1349 was a tragic year in the history of Kinsalebeg as this was in the time of the Black Death (1348-1350). Kinsalebeg was the only parish in Ireland where there were no recorded survivors of the Black Death and the whole parish was devastated. We will come back to this topic in later articles on the Black Death and Kinsalebeg land ownership during the De Clare and Badlesmere periods. It was during land ownership disputes in this period that facts arose confirming the devastation of Kinsalebeg in 1349. The following CIPM reference from “Inquisition held at Yoghill [Youghal] 22 Edward III [1349]” is also abstracted in The Historical Annals of Youghal4:

“Kynsall.[Kinsalebeg] John Haket holds free 1 car. [1 carucate] In le Rath [Rath], for 12s. 6d. yearly, with suit. John Gascoyng holds 1 car. in Tybergowe [Toberagoole] for 8s. and suit. There are also 24 Burgesses who hold 23 borough tenures, and yield yearly to the Lord of the manor of Inchecoyn [Inchiquin] 34s. 4d.They also hold 8 ac. [8 acres] in le Rothnes, at will, for 16d. The perquisites of the hundred are worth 12d. yearly, and the Ferry 34s. 4d. Yearly”.

Note: In the above entry “1 car.” means 1 carucate of land. This was the amount of land which could be ploughed by a team of eight oxen in a season. It was approximately 120 acres of land.

![]()

References to Ferry and Ferrypoint (1585-)

Date 18th July 1585: Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) confirms her grant of the lease of the ferry to the Corporation of Youghal at an annual rent of six shillings and eight pence. The following entry appears in The Ancient & Present State of the County & City of Cork10:

“Queen Elizabeth (1533-1603) on 18th July 1585 confirms her charter of 3rd July 1559 and also confirms that the passage, or ferry-boat, is by this charter, granted to the Corporation, at the rent of 6s. 8d. per annum. “

18th Jan 1610: The following entry in the Council Book of Corporation of Youghal9 for 1610 outlines those entitled to use the ferry and what passage costs were involved. Political perks were already well established even four hundred years ago as aldermen and town burgesses and their horses, families and staff were entitled to travel free of charge as long as they paid four pence each Christmas to the ferryman for the privilege. They were also allowed free passage of their Christmas cattle (beeves) and corn, which presumably were being shipped from the lush farmland of Kinsalebeg and its hinterland!

“... For the ferry-boat, we find that every Alderman and Burgess is to pay every Christmas 4d., in consideration that every such Ald. and Burg. shall have free passage for himself, his horse, and his people, so as said horse shall not be set to hire to any stranger or townsman.

We find that every Ald. and Burg. is to have free passage for their Christmas beeves, and for the Christmas corn; Date also that every freeman is to pay to the ferryman 3d. every Christmas, in consideration afsd.

We find that every inhabitant is to pay 2d. every Christmas for the former considerations.

We find that every freeman is to pay out of every horse or cow for his passage one white groat, toties quoties (ie as often as it happens).

We find for every household of corn, 1d., for every 2 bags of corn, 1d., so as they shall be brought to the ferry by Town inhabitants. “

Note: The white groat is a coin struck during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) and its value varied but in general terms three white groats were worth about four old pence.

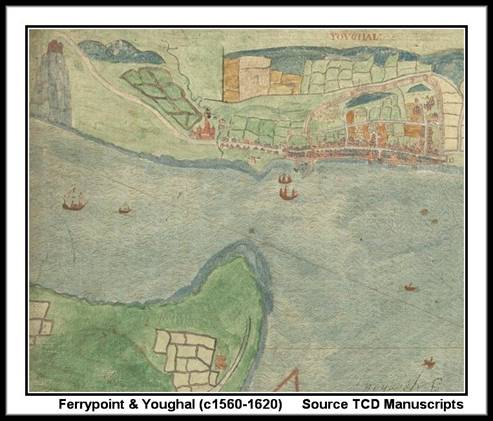

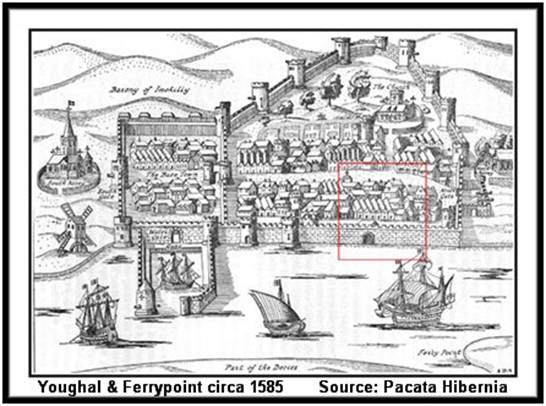

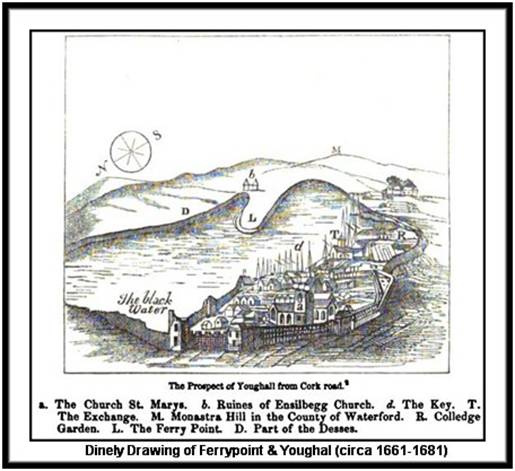

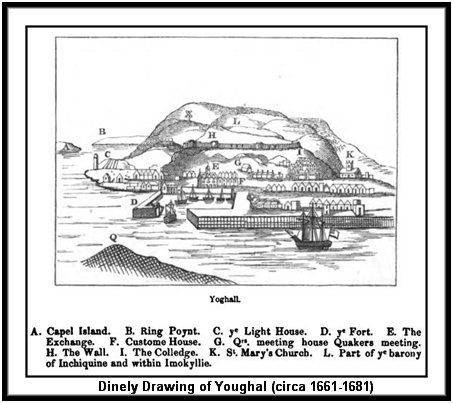

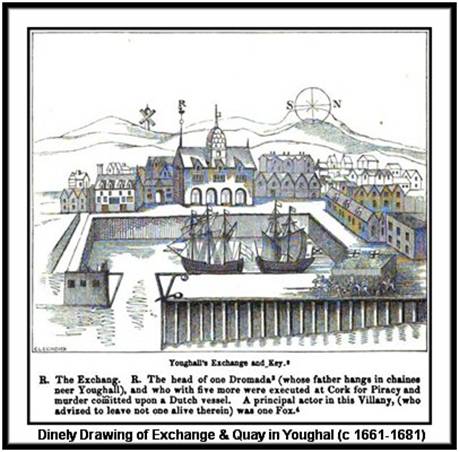

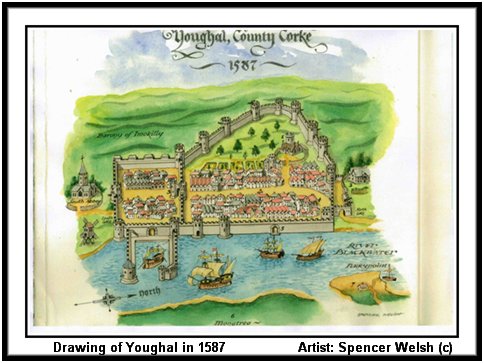

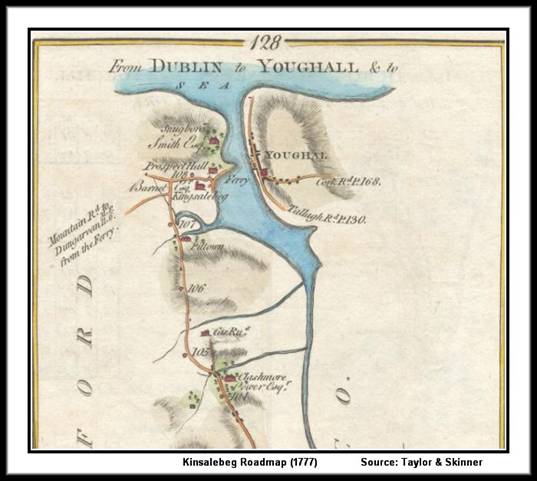

Date 1585 approximately: The earliest known maps of the Youghal/Ferrypoint area are from the Pacata Hibernia6 first published in 1633. These maps probably represent the area as it was around 1585. The image below shows the walls of the town with defensive towers. A couple of large cannons are shown pointing north on the right hand side of the map. On the left of the map is the South Abbey with a windmill just below it. On the bottom left can be seen a small inner harbour shown as Water Gate where ships could be unloaded onto the quays and into the town itself via the arched iron portcullis. The bottom of the diagram shows the Waterford side of the harbour with Ferry Point and Part of the Decies (Deeces).

Date 10th Jan 1611: The town corporation in Youghal had decreed that staff and family members of freemen of the town would be entitled to free travel on the ferry. Despite the above arrangement things did not always go smoothly as the following 1611 entry in The Council Book of Corporation of Youghal 9 outlines. James Kearnye was a councillor or freeman of Youghal and one of his employees had an unpleasant experience on a trip across the ferry to Ferrypoint. The employee was on his way to Ardmore to do a bit of “special business”. The employee understood that the trip would be free of charge as per the corporation rules. However the ferryman disagreed and took the passenger’s coat in lieu of payment. The passenger’s cap was taken in lieu of payment on the return trip from Ferrypoint to Youghal. Being in the middle of winter this no doubt caused some discomfort to Mr Kearnye’s employee. Mr Kearnye complained vehemently at the next council meeting in Youghal but nothing could be done about the matter as the ferryman had absconded to England, no doubt greatly pleased with his new coat and cap!

“Mr James Kearnye having complained, that notwithstanding he hath paid all offerings and duties accustomed to the ferry and passage, yet his man, sent over by him to Ardmore, about twelfth day last, about said Kearnye’s special business , had first his mantle, and upon his return his cap taken from him for his passage, contrary to the ancient custom of said passage. But in regard the lessee ferryman is now in England, this matter is to be forborn till his return”.

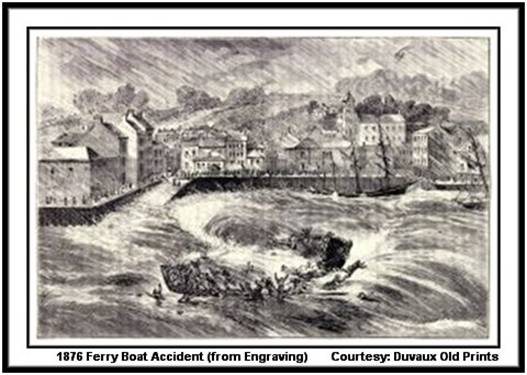

Date 14th September 1616: The diary of the Earl of Cork known as the Lismore Papers12 records a ferry boat accident between Youghal and Ferrypoint in 1616 when 30 people were apparently drowned. The entry was recorded by Richard Boyle, the then Earl of Cork, and indicates one of the many boat accidents that occurred over the centuries in the short but dangerous passage between Youghal and Ferrypoint. The River Blackwater meets the Atlantic Ocean here which results in dangerous currents and eddies, even on a relatively calm day. In windy or stormy weather the ferry journey often became extremely dangerous and resulted in many cancellations. The term “Holy Rood” refers to a cross or crucifix from the old English word “rood” meaning cross or from the Scottish term “haly ruid” meaning "holy cross". The 14th September was a day devoted to veneration of the cross in many religions and was known as “Holy Cross Day” in Anglican and Lutheran churches. The ferry accident therefore presumably took place on the day the entry was recorded in the diary on the 14th September 1616. The Lismore Diary entry was as follows:

“Holy Rood day the ferry boat of yoghall was caste awaie about xxx [30] persons drowned”

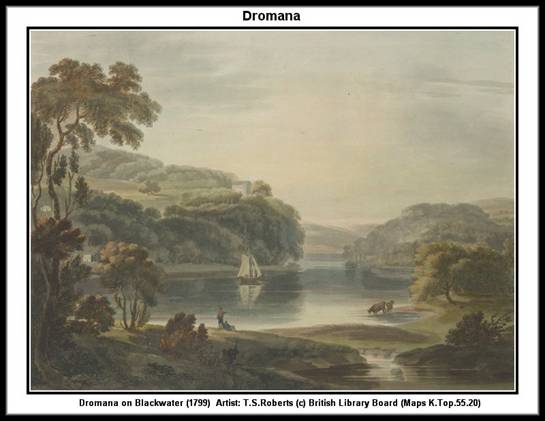

Date 6th April 1626: The following entry in The Historical Annals of Youghal4 notes correspondence between Mathew Bruning and Sir Thomas Wilson concerning the death of the Lord of the Decies namely John Og FitzGerald of Dromana in March 1626. The correspondence indicates that the last rebellion, the Desmond rebellions in the late 16th century, did not have much effect on the Dromana estate due to the influence of the Lord of the Decies. It refers to the Dromana estate as the Drum or the area “from the Ferry of Youghal to and beyond Dungarvan” even though the land of Kinsalebeg, including Ferrypoint, was in the ownership of the Walsh family of Pilltown in 1626. Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior of Pilltown had obtained this land after the breakup of the vast Desmond estates after the last rebellion. The entry states that in that area “hardly one plough stood still” during the last rebellion which implies that the Desmond wars did not really affect the area and life went on as normal, due to the powerful influence of the Lord of the Decies. The relatively peaceful period in the early part of the 17th century, between the Desmond rebellions and the Confederate wars, was soon to change with the rebellion of 1641. Amongst those in the vanguard of the Irish Confederate opposition to the English Parliamentarians in West Waterford in this rebellion were the fighting Walshs of Pilltown under the leadership of Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior, son of Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior, which is covered elsewhere in this history. The entry of 6th April 1626 in the annals was as follows:

“.... The beginning of March here (March 1626) died a worth gent., John FitzGerald, Lord of the Decies, Co. Waterford. A man nobly disposed unto the English, and of the greatest estate in that county. In the last rebellion, in all his country, called the Drum, from the Ferry of Youghal to and beyond Dungarvan, hardly one plough stood still.”

Date 27th June 1628: According to the following entry in The Council Book of Corporation of Youghal9 the lease of the ferry was in the hands of Gregorie Sugar in June 1626 at an annual lease cost of 12 shillings a year:

“That Gregorie Sugar shall have the ferry of Y. (Youghal) at 12li. yearly, to use all strangers, passengers, &c. with all respect, and for those that way to the market, taking from them but easy fees, and to that intent was his rent rebated.”

Date 27th April 1632: Youghal corporation introduced a law in 1632 to prevent porters at the various gates in Youghal from charging customs duty on the goods being brought across the ferry from Ferrypoint. Passengers with goods for the markets in Youghal were already being charged at Ferrypoint for their own transport and the carriage of their goods. A practice had developed whereby the porters on the gates in Youghal were putting an additional custom charge on goods coming across the ferry – it is not clear if this was an official custom charge or a perk for the porters. In any case the authorities felt that it was unfair that goods coming from Ferrypoint were often subject to both carriage charges and custom duties whereas the farmer coming in with a couple of pigs from Gortroe did not have to pay anything. The decision is recorded as follows in The Council Book of the Corporation of Youghal9 in 1632:

“Ordered, that no porter, &c., of the South gate, or any other Gate, shall take any manner of custom out of any goods transported or brought in the Ferry boat of Youghal to this town and market, but for the encouragement of those that come over the Ferry at Youghal, shall be custom free, and whosoever shall transgress shall forfeit 5s. and the porter discharged”.

Date 25th April 1636: The lease of the ferry from Youghal to Ferrypoint was given to a Mr Edward Stoutes in 1636 for a seven year period at an annual rent of twenty two pounds and ten shillings. This was a considerable amount of money in 1636 and in present day terms would have a value in excess of 100,000 pounds sterling. It gives an indication of the scale of the ferry operation in transporting goods and people at that time. The entry in The Council Book of Corporation of Youghal9 reads as follows:

“ The Ferry and Ferry boat of Youghal is demised to Mr Edward Stoutes, Ald., for seven years from 2 Feb last, for the yearly rent of 22li. 10s., said Ferry to be kept in good order and well furnished with men and sufficient boats. 5li. ster. is allowed to Patrick Polley in consideration of his expenses made in providing boats, by reason of a promise made unto him of the Ferry in Youghal, out of the Ferry boat rent.”

![]()

Irish Confederate Wars (1641-1649)

The period from 1641 to 1649 was another violent and tempestuous period in Irish history. Kinsalebeg was not immune from the hostilities and devastation brought about by the rebellion that took place. The period became known as the 1641-1649 Rebellion or the Irish Confederate Wars. It was complicated by a number of unusual alliances but we are primarily dealing with the war between the mainly Catholic Irish Confederates and the primarily Puritan or Protestant English Parliamentarians supported by the Scottish. The English Parliament had arisen against the monarchy of King Charles I and the king was dethroned. This resulted in some unusual alliances whereby some Protestant royalist supporters in Ireland fought on the side of the Irish Confederates in opposition to the Cromwell led English parliamentarians. The Irish Confederates were therefore, somewhat unusually, fighting on the same side as the King of England. The effect of the Irish Confederate Wars in Kinsalebeg and nearby areas is covered in greater detail in the history of the Walshs of Pilltown. The following overview is confined to events and commentary involving the Ferrypoint and Youghal in this period.

![]()

Siege of Youghal (1641)

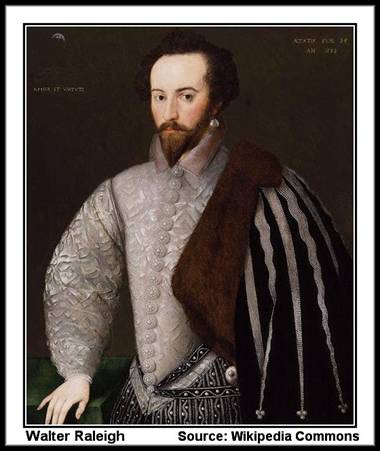

In 1641 Youghal was under siege from the Irish Confederate forces. The town was being defended by the 1st Earl of Cork Richard Boyle with approximately 1000 foot soldiers and 60 cavalry. In addition the townsmen themselves maintained another 15 companies with weaponry supplied by the Earl of Cork. Richard Boyle had purchased the 42,000 acre estate of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1602 for around 1500 pounds sterling, which was a very low price for the amount and quality of the land and associated property. The price was no doubt affected by the impoverished state of Sir Walter Raleigh’s finances and the debts which were owed by his estate. The land was mainly in the counties of Cork, Waterford and Tipperary and the estate was centred about their home base of Lismore Castle in County Waterford. The Boyles went on to increase the size of the estate and made large improvements after the neglected Raleigh years.

The Boyles would play a significant role in the Confederate Wars in support of the Cromwell led English Parliamentarians. They were initially supporters of the Royalists under King Charles but switched to Cromwell’s side after the king was overthrown. Indeed many years later they switched their support back again to the royalist side when the monarch was restored in England but that is a story for another day. However it shows that the Boyles were largely opportunist, whether in business or in war, and had ultimately no real allegiances aside from improving their own situation. Their vitriolic anti Catholic agenda was however a consistent position which they maintained throughout their lives. The Boyles were a large family but in the period under discussion we are largely concerned with four members of the family namely Richard Boyle 1st Earl of Cork and three of his sons Roger, Lewis and Charles Boyle. Roger Boyle was the most prominent of the sons and became the 1st Earl of Orrery and later Lord Broghill, by which name he is more commonly known. Lewis Boyle became Viscount Boyle of Kinalmeaky and was usually referred to as Kinalmeaky. The third son, Charles Boyle, became Viscount Dungarvan.

![]()

Earl of Cork describes situation in Youghal (1641)

Date 25th Feb 1641: The following extract is from a letter written by Lord Cork aka the Earl of Cork, Richard Boyle, to the Earl of Warwick in the early stages of the 1641 rebellion. The Earl of Warwick was an English colonial administrator and puritan who became commander of the British fleet in 1642. The “facts” in this type of correspondence have to be taken with a grain of salt as the contents are dictated by the requirements of the author at the time. In battle situations the number of the enemy killed or injured tends to be exaggerated and the losses minimised. The Earl of Cork, in this situation, was looking for additional help in the form of troops and finance so the tendency would be to paint a bleak picture of his current situation. He mentions that whereas his normal rental income was fifty pounds a day, a considerable amount of money in 1641, he was now reduced to the paltry income of fifty pence a week. In those days many of the large land owners had their own armies which in the main were made up of their own employees or tenants on their estates. They largely funded the cost of running the armies from their resources and relied on the relevant government or monarchy to refund, defray or supplement these costs. The situation in Youghal was undoubtedly very severe during the siege in 1641 and the hardship on the inhabitants was very severe. This letter outlines the stated position of Youghal and the Earl of Cork at the start of the rebellion on 25th Feb 1641 as outlined in The Historic Annals of Youghal4:

“Yesterday they [the rebels] took eight of my English tenants and hanged them up, and bound an English woman’s hands behind her, and buried her alive. My second son, Kynalmeaky [Viscount Boyle of Kinalmeaky] commands my new town of Bandon-bridge, where he hath found 500 foot and 100 horse, but no entertainment or pay. On 18th the enemies approached the Town walls, whereupon my son issued with only 60 horse and 200 foot, charged them in the van, they had a bitter fight. There are many of them wounded; he took 14 prisoners, whom he hanged by marshal law at the Town gates. ... I have, since the beginning of the Rebellion, at my own charge, kept 200 men here [Youghal] for securing the Town and Harbour; 100 horse and 100 foot at Lismore, which my son Broghill [Lord Broghill] commands, and daily kills of the Rebels and takes prisoners and preys of them. And I pay another 100 at Cappoquin, and whereas before, my revenue, besides my houses, demesnes, parks and other royalties did yield me 50li. per day rent, I have not now 50 pence a week coming in”.

![]()

Earl of Cork requests Vavasour assistance for Youghal (1642)

Date 12th January 1642: Richard Boyle, the Earl of Cork, sent a letter to Lord Goring on the 12th January 1642 requesting urgent assistance for the defence of Youghal which was under siege. Lord George Goring Earl of Norwich was married to Lettice Boyle, a daughter of the Earl of Cork. In earlier years Richard Boyle obtained a post for him as a colonel in the Dutch Army and Goring was later appointed governor of Portsmouth. Goring was a royalist supporter and in September of 1642 he was forced to surrender Portsmouth to the parliamentary forces. The following letter from the Earl of Cork to Goring outlines the desperate situation arising from the siege in Youghal and requests that Charles Vavasour and his army should be sent quickly to relieve the town. The letter from the Earl of Cork is recorded as follows in The Historical Annals of Youghal4:

“... And therefore, even upon the knees of my soul, I beg and beseech you to supplicate his majesty and the lords and commons of both houses of parliament, that this fruitful province of Munster (wherein are more cities and walled towns, and more brave harbours and havens than all the rest of the kingdom hath; and the English subjects that are herein, may not want of timely supply of men, money, and munition, be lost; nor the crown of England deprived of so choice a flower thereof; but that you will incessantly solicit the hastening over of the Lord Lieutenant with the army to Dublin, and Sir Charles Vavasor with his regiment to Yoghall [Youghal], with a liberal supply of arms and munition, whereof the province is in a manner utterly destitute. And therein, for God’s sake, let not the least delay be used, for if there be, all succours will come too late...”

![]()

Charles Vavasour’s Welcome from Ferrypoint (February 1642)

Date 25th February 1642: The above letter from Richard Boyle to Lord Goring resulted in the despatch of Sir Charles Vavasour with his troops to Youghal. Sir Charles Vavasour arrived in Youghal on 25th Feb 1642 with a regiment of 1000 men. When he came into the harbour he came under heavy fire from Ferrypoint where a battery of three heavy guns had been placed by the Irish Confederate forces. The guns had been brought from Waterford after the revolt in that city and were placed in Ferrypoint to “annoy the town” according to the description below in The Historical Annals of Youghal4. Vavasour and his troops eventually landed in Youghal to relieve the town after running the gauntlet of the heavy gunfire from Ferrypoint. Soon afterwards the Earl of Cork held a judicial session in the town where a number of the insurgent leaders were indicted for high treason. The 1st Earl of Cork died in September 1643, having lost the greater part of his estates during the 1641 rebellion. These estates were later recovered by his sons after the suppression of the rebellion.

“About this time Waterford revolted, and the Irish possessed themselves of the ordnance mounted on the fortifications. Three of the guns they transported to the ferry-point opposite Youghal, where they planted them in a battery to annoy the town. On the 25th February, Sir Charles Vavasour arrived in the harbour, with the long expected succours. He brought the King’s commission against the Rebels, and his own regiment of 1000 men, but neither money nor arms. Vavasour landed his men with no small difficulty, as the Irish battery on the Point continued playing on the boats, while the soldiers disembarked.“

![]()

Commission of Sir Nicholas Walsh of Pilltown (February 1642)

Date February 1642: The Historical Annals of Youghal4 describes the situation in the Ballyhoura Mountains in February 1642 when a battle was about to take place between the Irish Confederates and the English forces led by the President of Munster William St Leger. The Ballyhoura Mountains are situated on the borders of south-east Limerick and north-east Cork. The report details personnel involved in the impending battle and refers to the infamous alleged “forged commission” of Sir Nicholas Walsh of Pilltown, which is covered in greater detail under the separate Walsh of Pilltown history. In summary Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior of Pilltown was reputed to have presented a sealed commission to the President of Munster William St Leger. The sealed commission was from King Charles of England and stated that the Irish Confederate leader, Lord Montgarret, was authorised by King Charles to raise four thousand troops on his behalf to fight on the Irish Confederate side. William St. Leger was fighting against the Irish Confederates but was loyal to the king so the commission put him in a quandary. The Boyle brothers Broghill, Kinalmeaky and Dungarvan were with St. Leger at the time he received the commission and immediately declared that it was a forgery and that he should ignore it. St Leger however decided that the commission was authentic and withdrew his forces from the impending battle. The decision apparently caused St. Leger much distress. He rapidly descended into some form of insanity and died within a few months of the event. The article eloquently stated that his decision to accept the authenticity of the commission “threw him into a disorder” which is a nice way of describing his condition.

The question as to whether the commission from King Charles, which Nicholas Walsh presented to St Leger, was genuine or forged caused much argument on all sides both at the time and subsequently. On the balance of evidence it appears that King Charles was indeed trying to muster support from the Irish Catholics and had issued commissions to that effect. However when evidence of this became prematurely public King Charles was forced to deny it and this led to the accusation that the commission was forged by Sir Nicholas Walsh in his castle at Pilltown. The “dirty tricks” department of the English monarchy was apparently up and running in 1641 and with Cromwell in the other corner it would be unreasonable to expect high standards in governance. The subject of the “forged commission”, and indeed other commissions, is covered in detail under the Walsh of Pilltown history. The following is the text of the February 1642 entry as outlined in The Historical Annals of Youghal4:

“Early in February the Lord President, Sir William St. Leger, posted himself at the pass of Redshard in the Ballyhowra [Ballyhoura] mountains, hoping to provoke a battle with the Irish army. He had with him 300 horse and 900 foot, and was assisted by the Earl of Cork’s three sons, the Lords Dungarvan, Broghill, and Kynalmeaky, the Earl’s son-in-law, Lord Barrymore, Sir Hardress Waller, Sir Edward Denny, Sir John Browne, Major Searle and Captain Kingsmill. The Irish general, Lord Montgarret, sent a trumpeter demanding a parley; and Walsh, a lawyer, who resided at Pilltown, opposite Youghal, submitted to the President [William St Leger] a large parchment, in which appeared a formal commission, with the broad seal attached, authorizing Lord Muskerry to raise 4000 men for the King’s service. St. Ledger peruses the document, and, believing it to be genuine, he agreed to articles, 10th Feb., by which he bound himself to retire to some convenient place, and disperse his forces, until further directions from His Majesty. By his discovery of the cheat, when it was too late, preyed so heavily on his mind, that it threw him into a disorder, of which he died a few months after at his house, Doneraile.”

![]()

Youghal Support of Kinsalebeg farmers (October 1642)

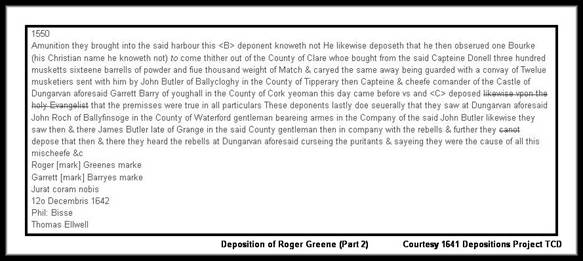

Date December 1642: A witness statement or deposition was taken in December 1642 from a Roger Greene of Ballyhambles which appears to be in the parish of Kilwatermoy in the barony of Coshmore and Coshbride. We include it here because this is the first recorded instance of a party of people from Youghal crossing the ferry to Ferrypoint to assist the farmers of Kinsalebeg with the harvest! The 1641 Depositions18 were witness statements taken mainly from Protestants, but some Catholics, at the time of the 1641 rebellion. These witness statements of depositions recorded such things as the loss of goods and damage to property as a result of rebel activities and as such were intended to be used as kind of insurance claims for losses incurred. They also outlined the alleged crimes committed by Irish insurgents or rebels as they were called. It was the intention that the statements would be used later in the trials of alleged offenders and in many cases they were used in military “trials” which resulted in the hanging and imprisonment of alleged rebels. They describe military activities, assaults, strippings, burnings, robbery, hangings, rape and murder together with a litany of other serious offences. The names of those who were alleged to have committed the crimes are named in the statements. In some cases literally dozens of names were given which was a testimony to both the eyesight and the memories of the witnesses. Many of the alleged crimes were carried out under the cover of darkness which would have further added to the difficulty in identifying members of the raiding parties. The veracity of these witness statements has been the subject of much historical debate and suffice to say it is unlikely that they would be accepted as evidence in any modern court of law. However they are an important and unique source of information on the 1641 rebellion regardless of the veracity of the content. There is no doubt that these were difficult times and the death and destruction on all sides of the conflict was enormous. The famous family of fighting Walshs of Pilltown in Kinsalebeg were regularly mentioned in witness statements as being leaders in many of the rebel attacks in the West Waterford and East Cork area.

The witness statement of Roger Green describes a journey across the ferry from Youghal to Ferrypoint taken by himself and eleven other people in October 1642. The twelve Youghal area residents were sent to Ferrypoint by Sergeant Major Matthew Appleyard, who was Governor of Youghal at the time, in order “to reape & bind some of the rebells corne” on the Kinsalebeg side of the harbour. We can assume that this was not a meitheal from our Youghal neighbours to help out with the harvest in Kinsalebeg and was an attempt to plunder corn for their own use in a besieged Youghal. In any case the Irish rebels on the Kinsalebeg side of the harbour did not take too kindly to the offer of assistance and promptly captured the whole working party. They were locked up in Dungarvan Castle which was under control of the rebels at that time having been captured by Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior and his colleagues earlier in the year. It was during this attack on Dungarvan that Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior was killed. The raiding party from Youghal were very lucky that they were treated so lightly in the circumstances. There is little doubt that if a rebel raiding party from Kinsalebeg made an incursion into Youghal in this period they would have found themselves hanging from the Clock Gate if caught.

Roger Green gives his description of events which he said occurred during his imprisonment in Dungarvan Castle. He describes the arrival in Dungarvan of ships from France and Spain with arms and ammunition for the Irish Confederates. Roger Green and Garret Barry of Youghal went on to list the names of Irish Confederate leaders who they alleged they saw in Dungarvan during their incarceration. These included John Butler of Ballycloghy Co Tipperary, John Roch of Ballyfinsoge Co Waterford and James Butler of Grange Co Waterford. The following are the transcribed details of the Roger Greene witness statement with some minor alterations and some explanations in brackets to make it more readable but by and large we have left the original spellings as they were transcribed. It is difficult to read but we are including the transcription and the original deposition here as they give a fairly authentic reproduction of the original witness statement as outlined by Roger Greene:

“The examination of Roger Greene late of Ballyhambles Parish of Killotomoy [Kilwatermoy] barony of Cosemore and Cosebridy [Coshmore and Coshbride] and within the County of Waterford husbandman taken before us upon oath of the holy Evangelist by vertue of a Comission beareing date at Dublin the 5th day of March last concerneing the losses and sufferinges of his Maiesties subiects brittish and protestants within the Province of Munster &c deposeth & saith:”

“That on or aboute the first day of October last this deponent [Roger Greene] together with the number of eleven men & women vizt Alexander Crase, Garrett Bary, Rich West, William Watt, William O Hea [ ] Ann Merryvile the wife of John Merryvile Ursula Gullyferr & others were sent by directions from Sarjeant major Apleyard Governor of the Towne of youghall ouer the ferry of youghall aforesaid into the county of Waterford to reape & bind some of the rebells corne namely William O Shighane for one, whoe noe sooner fell to woorke aboute the reapeing of the said Corne but the enemy consisting of the number of forty horse & three score foote or therabouts came and assaulted this deponent & the rest & being apprehended by them they caryed them prisoners to Dungarvan a place of the enemyes randezvous & being then comitted a long time then & there they observed two barques come in to Dungarvan aforesaid one wherof came out of Spayne laden with armes and amunition comanded by one Captian John Donnell a native of this kingdome, & thother laden with salte powder and armes newly come out of ffrance but what quantity of armes & other Amunition they brought into the said harbour this deponent knoweth not. He likewise deposeth that he then observed one Bourke (his Christian name he knoweth not) to come thither out of the County of Clare whoe bought from the said Capteine Donell three hundred musketts sixteene barrells of powder and five thousand weight of Match & caryed the same away being guarded with a convoy of Twelve musketiers sent with him by John Butler of Ballycloghy in the County of Tipperary then Capteine & cheefe comander of the Castle of Dungarvan aforesaid. Garrett Barry of youghall in the County of Cork yeoman this day came before us and deposed likewise upon the holy Evangelist that the premisses were true in all particulars. These deponents lastly doe severally [say] that they saw at Dungarvan aforesaid John Roch of Ballyfinsoge in the County of Waterford gentleman beareing armes in the Company of the said John Butler likewise they saw then & there James Butler late of Grange in the said County gentleman then in company with the rebells & further they canot depose that then & there they heard the rebells at Dungarvan aforesaid curseing the puritants & sayeing they were the cause of all this mischeefe &c.

Roger [mark] Greenes marke

Garrett [mark] Barryes marke

Jurat coram nobis

12o Decembris 1642

Phil: Bisse

Thomas Ellwell”

The following is the image of the above 1641 deposition in its original form – the two images are part of the same deposition. The sections of text which were deleted, altered or crossed out were altered at the time or shortly afterwards:

![]()

William Penn and the Siege of Youghal (1645)

Date July 1645: The following details of the involvement of William Penn and Ferrypoint in the siege of Youghal during the 1641-1649 rebellion are largely taken from William Penn’s Memorials2. William Penn Senior was father of the William Penn Junior who in later years was to become the Quaker founder of the state of Pennsylvania in the USA. Charles II signed over the area of Pennsylvania to the Penn family in 1681 in lieu of a 16,000 pounds debt he owed to William Penn Senior. William Penn Junior spent a number of years in Shanagarry near Youghal from 1666 onwards looking after the estates that his father had received from Cromwell. He became a Quaker during the period he spent in Shanagarry much to the annoyance of his father. William Penn Senior, who later became Admiral Penn, was 23 years of age in 1644 when he was given command of the 300 ton Fellowship with 110 men and 28 guns. The ship was one of the Irish Guard fleet, under the command of Admiral Richard Swanley, which was responsible for protecting both sides of the Irish sea from the naval forces of the then King of England Charles 1. In 1645 Penn was put in command of the 539 ton Entrance ship which was equipped with 38 guns. At this stage William Penn was effectively a vice-admiral in Swanley’s fleet.

On the 5th July 1645 Admiral William Penn was instructed by Lord Inchiquin (aka Murrough O’Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin, “Murrough the Burner”) to assist in the relief of the town of Youghal. Youghal was at that point under siege by the Confederate Irish rebel forces, led by Castlehaven (aka James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven), who had some heavy artillery and forces on the Ferrypoint side of the harbour. Penn’s fleet set sail from Kinsale to Youghal on 8th July 1645 with a hundred soldiers on board and arrived in Youghal later that day. Captain Boyle, who was a commander in Youghal, came on board Penn’s ship and briefed him of the poor situation in the town. On the morning of the 9th July Penn went ashore in Youghal and met up with Sir Percy Smith, the deputy governor of the town. Smith instructed him to place the merchant-ship Nicholas in the bay at the south end of the town and the Duncannon frigate at the north end of the town. When Penn was returning to his barge after the visit to Percy Smith an unfortunate accident took place according to Penn. When Penn answered the governor’s five gun salute with a three gun salute from his own barge there was an accident in firing the last gun. According to Penn:

“at the firing of the last gun, the piece not being well sponged, took fire, as one of our men was ramming home the cartridge, and so unhappily blew off one of his hands.”

On the 16th July 1645 the Irish rebel forces under Castlehaven were seen to be planting additional long range guns in the hill of Monatray on the east side of the harbour. Penn’s forces attempted to fire on the rebel gun fort but the guns were out of their range. During the night of 17th July Castlehaven had placed three additional guns on Ferrypoint and commenced to fire on the Duncannon when morning broke. According to Penn:

“17th.- By break of day, the enemy had made a fort of cannon-baskets on the east side, opposite to the town fort; and having drawn down three guns into their work, shot at the Duncannon frigate, she at them again; but by an un-expected accident (as we after were informed) the powder of their store took fire; which being blown up, she immediately sunk, and being but little more water than she drew, her stern was above water, when her bilge lay on the ground. All those which were afore the mast suffered, in number 18, with one woman; she, with two of the 18, being, as was reported, in the powder-room, when the powder took fire. Seven more of the company were very much scalded and bruised; but, God be praised !, we have hope of their recovery.”

Penn therefore lost 18 men in this encounter or seventeen men and one woman to be precise. It is unusual that a woman was among the 18 casualties of the sinking of the Duncannon as it was not common to have women manning guns or indeed to be present on war ships in those days. According to Penn the woman was in the powder-room with two men when the powder took fire. One wonders firstly why she was on the ship at the time and more critically what she was doing in the gunpowder room. Is it possible that she may have misinterpreted the Powder Room sign on the door of the gunpowder room? What may have been intended as an innocuous trip to powder the nose and have a quick smoke ended up in a horrible tragedy as the ship blew up with disastrous consequences. Penn’s description of the blowing up of the Duncannon is at variance with that of Castlehaven who claims he blew the ship up with cannon fire from Ferrypoint.

Later on the afternoon of the 17th Penn, together with Captain Philips, went ashore in Youghal to visit the deputy governor Percy Smith. While they were in Youghal two of the enemy Confederate forces boats were seen coming down the river apparently laden with provisions and ammunition for the Confederate forces on the Ferrypoint side. Penn ordered his barge to pursue the Confederate boats but they had to abandon the pursuit as they came under fire from the Ferrypoint. Penn, together with the governor Percy Smith, Lieut Colonel Loftus, Lieut Colonel Badnedge and with some others were watching these developments from the wall on the Youghal side of the harbour. Penn’s bad experiences in Youghal were set to continue however. Lieutenant Colonel Loftus and Lieutenant Colonel Badnedge, together with two other soldiers, were killed by artillery fire from Ferrypoint. Penn described the incident as “the enemy made a most unhappy shot from the other side of the water”. The only two to escape the attack were William Penn himself and the governor Percy Smith who both made a hasty retreat “with the stones which flew thick about our ears”. The following was Penn’s account of the latest set of events:

“the enemy made a most unhappy shot from their fort on the other side of the water, which killed the two lieut.-colonels, and two soldiers; five others were carried away, supposed to be dead, but were presently found indifferent well, having no great hurt. Only the governor and myself escaped untouched, but with the stones which flew thick about our ears; for which deliverance God make me for ever thankful! We quit the fort, and went into a house hard by. I requested Sir Percy Smith to despatch a messenger with this sad news to my Lord of Inchiquin, as also for some other officers in the room of those gentlemen that were slain; which he did the same night.”

William Penn was lucky to survive events of the 17th July 1645, particularly with the accurate gunfire from the Confederate forces on Ferrypoint. It was in stark contrast to the wild shooting seen on the Ferrypoint in the 1960’s when we participated in Gaelic football, hurling and camogie matches! William Penn’s bad day on 17th July was not at an end however. The men injured on the ill-fated Duncannon were brought aboard the Entrance and Penn ordered the Duncannon’s captain and gunner together with carpenters from the Nicholas to go back on board the Duncannon to salvage the sails, rigging and guns. Those familiar with Youghal Bay will be aware that the water is not very deep in some locations so part of the Duncannon was still visible above water. However the ship was listing to the port side and the guns on that side were underwater. The Duncannon’s crew refused Penn’s orders to go back on board the ship. They maintained that they had lost everything already and did not wish to lose their lives as well from enemy gunfire coming from the Ferrypoint side of the harbour. The following morning Penn sent in his barge to assist the Duncannon crew in the salvage operation. The Duncannon crew still refused to cooperate and Penn eventually had to order six of his own gunners to salvage what they could from the stricken Duncannon. They eventually retrieved a couple of the best guns and some ammunition.

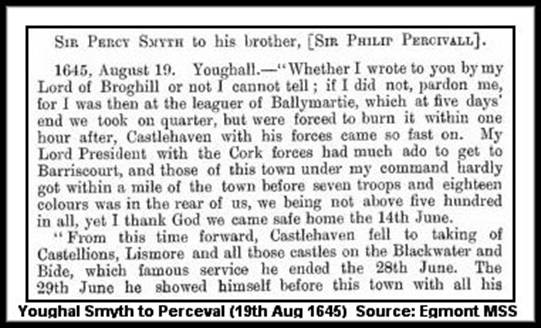

The following August 1645 entry in the Earl of Egmont manuscripts20 details a letter from Sir Percy Smyth to his brother-in-law Sir Philip Perceval which describes the siege of Youghal and the attacks from Ferrypoint. Smyth and Perceval were married to sisters Isabella and Catherine Ussher, who were daughters of Arthur Ussher and Judith Newcomen. Percy Smyth of Ballynatray was Deputy Governor of Youghal at this time and the town was under siege from Confederate forces. Smyth outlines the attacks on Youghal from Castlehaven guns on Ferrypoint and the resulting sinking of the Duncannon as well as the deaths of three soldiers including officers Loftus and Budnedge. Penn had indicated that four soldiers had been killed.

On 19th July 1645 Penn became aware that the Confederate forces had placed another gun on the eastward point of the harbour’s mouth and were now firing on the ship Nicholas captained by Captain Bray which was anchored on the south side of Youghal harbour. The exact location of this gun is unsure but we assume the Confederate gun was placed somewhere between Ferrypoint and East Point on the hill of Monatray across from the mouth of Youghal harbour. The firing accuracy from the Waterford side of the harbour continued and Penn incurred additional casualties with two men killed and two injured on the Nicholas. This is Penn’s account of the event:

“19th – In the morning, by break of day, the enemy had planted a gun on the eastward point of the harbour’s mouth, and made divers shot therewith at Captain Bray, he at them again; but before he could get his anchors on board, two of his men were killed and two hurt by the rogues, who shot him between wind and water, and several times in the hull. At last, weighed, set sail, and, coming forth, anchored by us”.

Note: “Between wind and water” means that part of a ship's side or bottom which is frequently brought above water by the rolling of the ship, or fluctuation of the water's surface. Any damage in this area just below the waterline is obviously dangerous.

The siege of Youghal continued for a number of months with varying degrees of success on both sides. The Youghal garrison was able to get much needed supplies on a number of occasions by running the gauntlet of the Confederate forces guarding the harbour entrance. On the 7th August 1645 William Penn left Youghal and sailed for Cork. A few days later he was somewhat surprisingly relieved of command of his ship Entrance by the arrival of Captain John Crowther who also took over as vice-admiral of the fleet. William Penn did not remember fondly his visit to Youghal and it is unlikely he ever returned to take a holiday in Ferrypoint after the welcome he received from the rebel forces on that side of the harbour.

In September 1645 Lord Broghill had effectively relieved Youghal when he arrived with troops from England. Broghill was never shy in blowing his own trumpet and outlined the details to William Lenthall who was Speaker in the British House of Commons in 1645. Broghill stated that the siege was at an end due to his own actions and that the great guns, including any remaining on Ferrypoint, were now silenced. Some of his words to William Lenthall are recorded as follows in The Historic Annals of Youghal4:

“Youghal was relieved after three months’ siege by the forces brought over by Broghill. The enemy drew off 5 or 6 miles. The besieged, by a brave sally a fortnight ago, routed the enemy, seized 2 great guns they had planted at both sides of the harbour”.

![]()

Castlehaven and General Preston during Siege of Youghal

Castlehaven had at this stage, in the autumn of 1645, placed the main body of his army at Ballynatray, about four miles north of Youghal, and was operating a strategy of attempting to starve out the town with no great success. He maintained his gun positions at the mouth of the harbour and at Ferrypoint. This siege was not effective and whereas the Confederate forces had great success with relatively stationery targets they were apparently much less successful with moving supply ships coming into Youghal. Castlehaven was unwilling to invade Youghal again as he feared the strength of the garrison so a kind of stalemate existed. Castlehaven therefore lost a great opportunity to bring the Munster campaign to a successful end for the Confederate forces as the parliamentary forces were in a state of disarray at that point. In essence Castlehaven lived up to his reputation as being an erratic and somewhat inconsistent general - he had some great military successes particularly in Munster against Murrough O’Brien (Lord Inchiquin) and others but also had some failures of which Youghal was ultimately one.

Eventually the Confederate supreme council lost patience with Castlehaven and they sent General Preston to Youghal in October 1645 to assist with the siege. Castlehaven had served as a commander of cavalry under General Thomas Preston in Leinster in 1641 and in many ways the combination of Castlehaven and Preston was a formidable military outfit which Padraig Linehan outlined in his book Confederate Catholics at War 1641-493. The combination never quite managed to get their act together in the siege of Youghal however. Preston was unhappy when he found out that he was to act under the command of Castlehaven and proceeded to camp at a distance from the town. Castlehaven, a notoriously touchy individual, was somewhat peeved that it was perceived by the ruling supreme council that he was unable to capture Youghal. In any case the Confederate forces failed to capture Youghal and the parliamentary forces remained in command of the town. This situation continued in the following years under the formidable influence of Lord Broghill and Cromwell. The following excerpts are taken from The Historic Annals of Youghal4 giving the status of the town on 29th October 1645:

“The Siege of Youghal: Youghal holdeth out very stoutly, considering the position they are in.” And also “About the beginning of this month Preston came with his forces and joined Castlehaven for besieging Youghal. They have placed ordnance on both sides of the harbour, six on the Passage point, and as many at this side at the nunnery. The town is very much straightened for provisions, for although they have not passing 1400 fighting men, yet they have at least 6000 women and children so that 100 barrels of wheat is but a pound of bread for a soul, considering how it may shrink in the baking and distributing.” And also “One thing, we have all manner of grain here exceeding plentiful; wheat at ten shillings per Barrell containing 5 Winchester bushels, oats at three, and barley at seven shillings. Without this, Youghal had been lost long since, our only misery is, we want wherewith to buy and pay for it. Since this, news came that Lo. Inchiquin hath not only relieved Youghal, but raised the siege and given the rebels great slaughter”.

![]()

Castlehaven overview of Munster campaign (1645)

In his memoirs5 Castlehaven gives some details of the Munster campaign and the siege of Youghal. The following details are taken from the above memoirs with the text in italics indicating actual quotations from the memoirs. In the period up to the spring of 1645 Inchiquin had overrun Munster and had shown little mercy to those he had conquered. Castlehaven states that:

”All this while my lord of Inchiquin over-run Munster, and coming to Cashel, the people retired to the Rock, where the cathedral church stands, and thought to defend it. But it was carried by storm, and the soldiers gave no quarter; so that, within and without the church, there was a great massacre, and amongst others more than twenty priests and religious men killed. Towards the spring the supreme council ordered me to go against Inchiquin, and to begin the field as early as I could. The enemy in this province had always been victorious, beating the confederates in every encounter, having never received any check”.

Castlehaven successfully attacked a number of towns and fortresses in the Munster area before his arrival in Youghal starting with Cappoquin on 5th April 1645. He states:

“Soon after, that is, about the fifth of April [1645], I marched to Caperquin [sic Cappoquin], my army consisting of about 5000 foot and 1000 horse, with some cannon”.

Cappoquin eventually surrendered. He also outlined his successes with attacks on Dromana, Mitchelstown, Fermoy, Mallow, Doneraile, Liscarrol and Castlelyons. Castlehaven eventually arrived in Youghal and he describes it as follows:

“from this castle [Coney-Castle] I marched to Youghall, and encamped loosely before it, thinking to distress the place; and towards the sea, near Crocker’s works, I sent Major-General Purcell with 1500 men, and some small pieces, to hinder succour that might come by sea. Whilst this was doing, I went with a party in the night, and two pieces of cannon, and passed the Black-water at Temple-Michael, and before day had my two guns planted at the ferry-point [Ferrypoint], over against Youghall, and within less than musquet shot of two parliament frigates: at the second shot one blew up, but some days after the enemy made a sally from Crocker’s works, and ill-treated Major-General Purcell, taking one of his guns.”

The above is the full account by Castlehaven of the attack on Youghal and is somewhat less detailed than Penn’s account of the same period. It was apparent that Castlehaven, together with Major-General Purcell, had made an attempt to capture the town but they were repulsed by the garrison at Youghal. They were subsequently reluctant to repeat the attempt. Castlehaven makes no reference to the arrival of General Preston in Youghal to assist him in the siege. It is interesting to compare the circumstances of the sinking of the Duncannon as described by Penn with that of Castlehaven. Penn maintained that the Duncannon was sunk as a result of an explosion in the powder room whereas Castlehaven insisted she was sunk as a result of gunfire from Ferrypoint. We will probably never know what really went on in the powder room of the Duncannon before the ship was sunk but it makes a great story! Castlehaven’s account of the Youghal siege concludes as follows:

“Soon after this there came a fleet of boats, and larger vessels, sent by my lord Inchiquin, from Cork, with supplies of men and provision, and succoured the town; on which I marched off, and trifled out the remainder of that campaign in destroying the harvest; only a party of my men attempted to plunder the great island, near Barry’s court; but being ill guided in passing, and the sea coming in sooner than they expected, their design failed”.

At the end of November 1645 Castlehaven retired his forces to Cappoquin for the winter and he himself then left for Kilkenny where peace discussions were taking place.

Notes re some key figures involved in the siege of Youghal in 1645:

Admiral Sir William Penn was commander in the Commonwealth Navy during the English Civil War 1642-1651. He was father of William Penn Jun who was born in October 1644 and became founder of Pennsylvania in later years.

Lord of Inchiquin, Chief Governor of Munster, otherwise Murrough O’Brien was Chief Commander of the Protestant parliamentary forces in Munster in 1645. He was nicknamed “Murrough the Burner” for his scorched earth military policy.

Lord Broghill otherwise Roger Boyle and later 1st Lord Orrery was Governor of Youghal in 1644-49. He was a major supporter of Cromwell and the Parliamentary forces in the 1641 rebellion.

Sir Percy Smith (Smyth), Knt was Lieutenant-Colonel, and Deputy Governor of Youghal in 1645.

Lord Castlehaven otherwise James Touchey 3rd Earl of Castlehaven was a commander of the royalist forces in the 1641 rebellion.

Duke of Ormonde otherwise James Butler was an Anglo-Irish statesman and soldier who led the fighting against the Irish Catholic Confederates from 1641 to 1647. He later became the leading commander of the Royalist forces and fought against the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.

![]()

Arrival of Cromwell in Youghal via Ferrypoint (1649)

Date August 1649: Oliver Cromwell was prominently involved on the Puritan parliamentary side of the civil war conflict between the British Parliament and King Charles I, which resulted in the execution of Charles on the 30th January 1649. The painting below is a depiction of Cromwell checking the coffin of Charles I as if to make sure he was really dead. Cromwell arrived in Ireland in August 1649 determined to subdue the rebellion and to destroy royalist support in Ireland which included the Catholic Irish as well as many of the mainly Protestant Anglo-Irish families. It was an unusual situation that the so called “Irish rebels” in this case were actually supporting the King of England. In the following months Cromwell led one of the bloodiest and most brutal campaigns ever to have taken place on Irish soil and to the present day Cromwell remains a figure of hate in Ireland. His campaign from Drogheda to Youghal was a trail of massacred garrisons, lootings, burnings, hangings and debauchery. The history of this bloody period is well recorded and we are not going to cover it here. His bloody campaign was temporarily halted at Waterford where his siege of the city was unsuccessful. He was eventually forced to abandon the attack on Waterford on 1st December 1649 and he moved on to Dungarvan which was captured with the help of Roger Boyle 1st Earl of Orrery also known as Lord Broghill. Cromwell and his army then set out for Youghal where they planned to spend the winter and where they received a great welcome. It was apparent from correspondence and discussions between Cromwell and Youghal/Broghill that there would be no resistance to Cromwell in Youghal. Indeed Cromwell had issued instructions to the mayor of Youghal as far back as May 1649 regarding the supply of provisions which he expected Youghal to deliver to him in Ross Co Kilkenny for the journey to Youghal. The Historic Annals of Youghal4 record the following letter received by the Duke of Ormond from the Lord Lieut.-General of Ireland (Cromwell) dated 11th May 1649:

“Ormond. – We taking into our consideration the absolute necessity of having a certain quantity of biscuit forthwith provided, for the use of his Majy. Army, and for the more speedy effecting thereof, have thought fit that the same be appointed to be done in several parts of the kingdom. We do therefore hereby require the Mayor of the town of Youghal to take present order, that there be four thousand weight of biscuit made in that town, for the aforesaid use, and that the same be sent by water to Ross, in such safe way as it may be fit for a present march, and that to be done at farthest by the last of this present May. And for satisfaction of the said quantity of biscuit, and all charges about the same, it is to be by you defalked out of the applotments and public dues now or hereafter to be raised in that town. Whereof the Commissioners and Receivers and all others therein concerned are to take notice. Given at our Castle of Kilkenny, this second day of May, 1649.”

The journey of Cromwell’s army from Dungarvan took them through Kinsalebeg. Cromwell decided to send some of his army to cross the River Blackwater at Templemichael while himself, and the bulk of the army, headed for Ferrypoint in order to cross by ferry to Youghal. The arrival in Youghal is described as follows in Ronayne’s History of the Earls of Desmond and Earl of Cork19:

“He arrived before Youghal in August, 1649 [December 1649]; part of his army crossed at Templemichael, the main body under himself came to the Ferry Point. He sent a message over to the mayor to provide at once boats for the transport of his army.”

Local Kinsalebeg folklore has it that he destroyed the church in Pilltown on his way through but there are no records to confirm this. It is interesting to note the “Ruines of Ensilbegg [Kinsalebeg] Church” on Thomas Dineley’s map of the Youghal area in 1661 (shown elsewhere). It is unlikely that Cromwell would have destroyed what was at that time a Church of Ireland church at Kinsalebeg even though the extreme Puritanism of Cromwell meant that he did not always look favourably on what he considered to be a too liberal wing of Protestantism. His views on various sections of the Protestant religion did not however come close to his absolute hatred of Roman Catholics whom he considered to be heretics. If a Catholic church did exist in Pilltown in 1649 then there may be some substance to the folklore that it was destroyed by Cromwell on his way to Youghal.