History of Kinsalebeg

Dowdalls of Pilltown Manor

Introduction

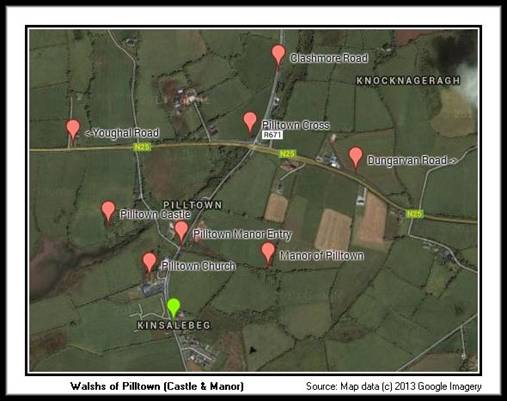

Captain Sir John Dowdall Senior was a leading English military leader who lived in Pilltown in the late 1500s and early 1600s. He was the first of the Dowdall family to settle in Pilltown and he lived in what was known at the time and subsequently as Pilltown Manor or the Manor of Pilltown. The Dowdalls were also leasing Pilltown Castle and around nine hundred acres of land in Pilltown. The Manor of Pilltown, Pilltown Castle and the associated land was the property of the Walshs of Pilltown around this period and the Dowdalls would have been leasing these properties from Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior. The Manor of Pilltown and the nearby Pilltown Castle were the primary Waterford residences of the Walshs of Pilltown over the centuries from the time of Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior but were being leased to the Dowdalls from around 1590 to 1620. There is no definitive date as to when Pilltown Manor and Pilltown Castle were built but the castle was in existence when the Desmond branch of the Geraldines (FitzGeralds) were rulers in this part of Munster before 1585 which was before the Walshs came to Pilltown. Pilltown Manor was also possibly in existence in some form before the arrival of the Walshs or Dowdalls but it would appear that some of the defensive structures around the manor were embellished by the Dowdalls during their tenure there. Before the Dowdalls took out a lease of Pilltown Manor from the Walsh family around 1590 it was apparently being leased by three other families over a period. According to Sir Richard Boyle’s notes in the Lismore papers the Manor of Pilltown was initially being leased to the Mannsfeyld [Mansfield] family followed by the Bluetts and finally the Reyly [Reilly] family before Sir John Dowdall took out a lease presumably from Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior.

![]()

Dowdalls in Manor of Pilltown

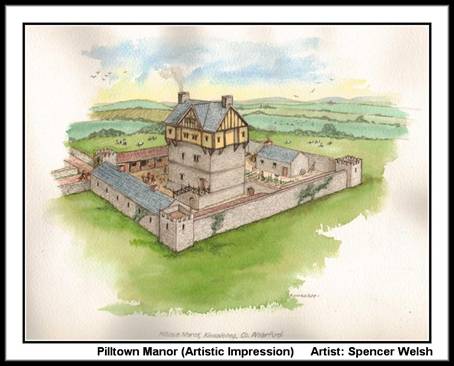

The Manor of Pilltown no longer exists and the main residence was demolished in the 20th century due to its dangerous state. The location of Pilltown Manor, opposite Pilltown Church, is shown in the above map. The piers to the entrance gate are still in existence at the junction of the side road which leads to the old Pilltown Mills. The side road is one hundred metres past Pilltown Church in the Pilltown Cross direction. Pilltown Manor appeared to have been quite a large structure with a defensive wall built around it along military lines. These defensive structures were most likely to have been added by Captain John Dowdall in view of what was an exceedingly dangerous and violent period in Irish history at the end of the 16th century. There is no doubt that Captain Dowdall had many enemies from his period as military commander of Youghal and it is unlikely that he was held in any great affection by the inhabitants of Kinsalebeg.

It would appear from Sir Richard Boyle’s notes in the Lismore Papers that the occupation or lease of Pilltown Manor before 1600 went from Mannsfeyld (Mansfield) to Bluett to Reyly (Reilly) and then to Sir John Dowdall Snr sometime possibly around 1590. Sir John Dowdall Jun then inherited the lease of Pilltown Manor which he subsequently passed on to Sir Richard Boyle Earl of Cork in 1620. The following drawing by Spencer Welsh is an artistic impression of how Pilltown Manor might have looked based on the outline dimensions of the ruins.

![]()

Dowdall as Military Commander in Youghal

Captain Sir John Dowdall Senior was born about 1545 in Shirwell Devonshire. He became a soldier in the army of Queen Elizabeth I in Ireland and in total had over forty years military service in Ireland in the period from around 1560 until his death in Pilltown Co Waterford in 1606. He received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth I for his Irish military achievements in this period. Captain Dowdall was for a period military commander in Youghal and was allegedly responsible for the death of the Franciscan priest Fr O’Neilan OSF in Youghal on 28th March 1580. It was thought that the original order may have come from Lord Arthur Grey who was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1580. In some records the name of the martyred Franciscan priest is given as Daniel O’Duillian and the year of his death is given variously as 1569 and 1580. The year 1580 however coincides more accurately with the period Captain Dowdall was based in Youghal and also with the date Lord Arthur Grey took up his appointment as Lord Deputy. Captain Dowdall apparently decided that Fr O’Neilan should be killed as a warning to members of the Catholic religious community in the area. The following description of the death and subsequent martyrdom of Fr O’Neilan (O’Duillian) was written by Fr Mooney in his 1627 overview of the Franciscans in Ireland published in “De Provincia Hiberniae Ordinis Sancti Francisci Tractatus”:

“For, when one Captain Dudal [Dowdall] with his troop were torturing him, by order of Lord Arthur Grey, the viceroy, first they took him to the gate which is called Trinity Gate, and tied his hands behind his back, and, having fastened heavy stones to his feet, thrice pulled him up with ropes from the earth to the top of the tower, and left him hanging there for a space. At length, after many insults and tortures, he was hung with his head down and his feet in the air, at the mill near the monastery; and hanging there a long time, while he lived he never uttered an impatient word, but, like a good Christian, incessantly repeated prayers, now aloud, now in a low voice. At length the soldiers were ordered to shoot at him, as though he were a target; but yet, that his suffering might be longer and more cruel, they might not aim at his head or heart, but as much as they pleased at any other part of his body. After he had received many balls, one, with a cruel mercy, loaded his gun with two balls and shot him through the heart. Thus did he receive glorious crown of martyrdom, the 22nd of April, in the year aforesaid.” Fr O’Neilan was subsequently declared to be a martyr.

![]()

Dowdall Military Campaigns in Munster

Captain Dowdall, together with Captain Zouche from Cork, was involved in the capture of Sir John Desmond and James Fitz-John of Strancally in Castlelyons in August 1581. Sir John Desmond aka Sir John Fitz-James was son of the Earl of Desmond and had been knighted in 1567. He was wounded during the capture and subsequently died on the journey back to Cork. He was nevertheless hung by his heels on the gibbet near the north gate in Cork and his head was sent for display at Dublin Castle. James Fitz-John of Strancally was also hanged and quartered in Cork after his capture. Captain Dowdall was the military commander when Enniskillen Castle was captured by the English in 1593. Enniskillen Castle was a key strategic target in the plans for the plantation of Ulster and even though it was recaptured at a later stage it was an important military victory at the time. He was also involved in the Battle of Belleek in 1593. After 1593 Captain Dowdall was mainly involved in military activities in the Munster area including action at Cahir Castle, Duncannon and he also gave military support to Sir Walter Raleigh at different stages during his tenure in Youghal. The following notes by the Rev. Alexander Grosart, in his 1886 review of the Lismore Papers, confirm the presence of Sir John Dowdall in Pilltown around 1591:

“Sir John Dowdall: His company of foot-bands garrisoned Youghal in 1588. In 1591 he was residing in the castle of Pilltown in co. of Waterford, on the Waterford side of Youghal harbour. In 1608-9 11 Jan. He wrote to Lord Salisbury from “Pilltown near Youghal” stating that he was “seventie years old” and asked for a pension or grant of land, as he had received no reward for his military services (H.M.S.P.O.).”

![]()

Dowdall Correspondence with Lord Burghley

Sir John Dowdall Senior wrote an interesting letter to Lord Burghley on the 9th March 1595. Lord Burghley, otherwise William Cecil, was chief advisor to Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign and Secretary of State for over seventeen years before 1572 at which point he became Lord High Treasurer. Dowdall’s observations were presumably based on his experiences around Pilltown and he gives a succinct image of the hardy Kinsalebeg men and women that lived in that period. John Dowdall described the letter to Lord Burghley as “my knowledge of the nature of the Irish nation” and it commences with the following description of the Irish as he saw them:

“they are a nation bred idly and in looseness of life, men full of agility and strength; they can endure hardness of diet, they care neither for good lodging, cold, nor wet, the most of them can swim, both men and women, they were fit to be made soldiers if they were faithful, but yet have always been rebellious, and hate to be governed by civil laws …”.

The letter goes on to give a detailed overview of the current situation in Ireland as he sees it ranging from the “superstitious seducing priests” to “each school overseen by a Jesuit, whereby the youth of the whole kingdom are corrupted and poisoned with more gross superstition and disobedience than all the rest of the popish crew in all Europe”. He gives a detailed portrayal of the Earl of Tyrone Hugh O’Neill who together with Hugh Roe O’Donnell was at that time in open rebellion against English rule in what was known as the Nine Years War or Tyrone’s Rebellion. Dowdall describes Hugh O’Neill as “the arch traitor” and it is obvious from the letter that he viewed him as a formidable foe. Sir John Dowdall had at this point spent over thirty years fighting various rebellions in Ireland and had no doubt arrived at a point where he knew that whereas the English might win some battles they would never win the war. He had obviously seen at first hand that the Irish were no ordinary people and had qualities of fighting spirit and endurance that he grudgingly envied. John Dowdall died in Pilltown in 1606 and little did he know that in the very manor in which he had lived as well as in the nearby Pilltown Castle yet another rebellious Irish dynasty was in gestation in the form of the fighting Walshs of Pilltown. He would of course have been well known to Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior but would have had no inkling that the following generations of the Walsh family would have been so active on the rebel confederate side from the start of the 1641 rebellion onwards.

![]()

Dowdall Correspondence with Sir Robert Cecil

Captain Dowdall had extensive correspondence with Sir Robert Cecil and other leading English military and political leaders particularly during the Nine Years war period of 1594 to 1603. Robert Cecil 1st Earl of Salisbury was a son of William Cecil Lord Burghley who died in August 1598. He was made Secretary of State after the death of Sir Francis Walsingham in 1590 and became the leading English minister after the death of his father. He was Secretary of State during the reign of both Queen Elizabeth I and King James and he also acted as spymaster for King James. The Dowdall correspondence was primarily concerned with the overall situation in Ireland together with his ongoing efforts to be compensated for the cost of his military activities in Ireland. In September 1598 Queen Elizabeth referred a Captain Dowdall petition to the Lord Admiral and Sir Robert Cecil. At this point Captain Dowdall would have been in charge of Duncannon Fort in Waterford harbour and would therefore probably have been away from his family in Pilltown for extended periods. In Dowdall’s petition he stated that he had received letters from his family outlining the serious situation in the vicinity of their home which we assume was a reference to Pilltown Manor in Kinsalebeg. He stated that his family in Ireland consisted of between fifty and sixty people and we know from other correspondence that he had twenty four children so presumably most of these were living in Pilltown. Family members were reporting to him that:

“there had been sundry persons murdered near his house”.

He went on to state that:

“He has lost by the extortion of the country gentlemen, cess of the soldiers, beans for the army, and thefts of cattle by neighbours, to the value of £140 since his departure. His family stand in doubt for their lives, as the nights grow long, without his presence for their defence, therefore he purposes to take his journey thither. (He) is at present without entertainment from the Queen, and hopes his former service is not forgotten. (He) has drawn blood of the greatest part of the nations of that kingdom, and is maligned for it, and they would require it with the loss of his head. (He) prays to be commended to the Lord President of Munster, to be one of that Council, and to be freed of all country charges and exactions, paying the Queen compensation for such land as he holds, which is 12 plough land. In recompense he will bear the charges of himself, his men and horses - 6th Sept 1598.”

![]()

Dowdall Family Difficulties in Pilltown

It would appear from the above correspondence that the Dowdalls had a difficult time in Pilltown and they had to pay particular attention to defences around their house. The twelve plough lands which Captain Dowdall stated he held would approximate to about 1500 acres. This we assume included the land of the Manor of Pilltown and also the land in Ardmore area which Dowdall had taken from Sir Walter Raleigh. Further details of the land, mostly in the Kinsalebeg area, under lease to Sir John Dowdall are included in his 1604 will.

![]()

Dowdall Ejects Walter Raleigh from Ardmore

When Walter Raleigh ran into difficulties with his Irish estates in the 1590s Captain Sir John Dowdall took advantage of the situation and was responsible for taking over some of Raleigh’s interests even though he was supposed to be giving military support to Raleigh. In 1593 Sir John Dowdall ejected Walter Raleigh from his tenure of the manor, lordship, castle, town and lands of Ardmore on the basis that Raleigh had no title to the property. Raleigh claimed that Bishop Witherhead of Lismore had demised the manor of Ardmore and other Ardmore lands to him in 1591 but Dowdall refused to relinquish the land. John Dowdall remained in possession of Ardmore despite the efforts of Raleigh until 1604 when King James granted this manor to Sir Richard Boyle, later Earl of Cork.

![]()

Financial Difficulties of Sir John Dowdall

John Dowdall seemed to have considerable problems in recouping the costs of his military activities in Ireland and was in constant communication with the authorities to obtain payment for his services. The cost of his various military campaigns was no doubt expensive and in addition John Dowdall apparently had twenty four children to support. In July 1598 the Lord Deputy Sir William Russell wrote a letter on Dowdall’s behalf to Sir Robert Cecil Secretary of State requesting recovery of payments for services of Dowdall as governor of Duncannon. Sir John Dowdall himself wrote to Sir Robert Cecil in Jan 1600 requesting payment for his services in Ireland over a period. The letter is interesting as it gives a good overview of the running of an army in 1600, conditions on the ground and the opinions and attitudes of those in charge. The letter is detailed in the Carew Manuscripts of the period 1589-1600 with spellings as per the original:

Date 2nd January 1600: Sir John Dowdall Snr to Secretary of State Sir Robert Cecil:

“At my last being at Court, I was a suitor for 1800li, laid out to support the men committed to my charge. After seven months’ detraction I was despatched to Duncannon with a promise from you and the rest of my Lords that I should be paid, and commanded to leave an agent to follow my suit. My agent has prevailed little. By disbursing that money I have engaged my whole estate. I must again repair in person to renew my suit. Since I saw you I have paid 400li, which I owed for victualling my soldiers.

Take this much from me, which I have gathered by experience these twenty years and upward. This nation is proud, beggarly, and treacherous, without faith or humanity, where they may overcome by tyranny. They are best to be commanded when they are poor, as may well appear by the tranquillity many years after they were plagued by the Desmondes’ wars, Boltinglasse’s, the wars of Connoght, and the revolt of a great many of them in Leynister; by which peace they grew as wealthy that for these 400 years past they were never so rich. Thereupon a rebellion was plotted at Lyfford, the Holy Cross, and such like superstitious places, by sundry seminary priests, as McCrast, Father Archer, and many the like sent by the Pope and the King of Spain. They were assisted generally by the townsmen and the nobility and gentry of both kinds, and were permitted by our State to grow to a head.

This nation is very apt in corrupting with bribes; if not a deputy or president, then some one that is greatest with him. The smoke of rebellion was first seen in the forerunner of the rebellion, magweyre, next in Tyrone, and “sequelarly” in his confederates in all parts of the kingdom. At first they doubted their ability to maintain wars, and in the beginning 10,000 men would have vanquished them whooly. They are maintained with powder, munition, and implements of war from Spain, Scotland, and the towns, and most of all from her Majesty’s army. They grow strong by the faction between the Deputy and Sir John Norris, and proud by Sir John Norris his temporising and forbearance of wars. They were encouraged by the disgrace of the Governor of Connoght, enabled by the overthrow at Blackwater;- proud, for that no resistance was made by the President to withstand so small an incursion as was made in Munster; and again proud, for that so worthy a man undertook the wars and made so short an abode. They are greatly strengthened for that they hear of a faction in the English Court.

Why are the forces so weak and poor? One cause is the electing of captains rather by favour than desert, for many are inclined to dicing, wenching, and the like, and do not regard the wants of their soldiers. Another cause is, for that the soldiers do rather mediate the disarmed companies that came out of Brittayne and Picardy, desiring a scalde rapier before a good sword, a pike without curettes or burgennettm a hagbutteyre without a murreon, which hath not been accustomed in this country but of late. The captains and soldiers generally follow this course, which is a course fitter to take blows than make a good stand. Many of the captains and gentlemen are worthy men, but most of them are fitter for the wars of the Low Countries and Brittayne, where they were quartered upon good villages, than here, or waste towns, bog, or wood, after long marches. Some captains have by their purse and credit held their companies strong, but have neither been repaid nor rewarded, and have fallen into great poverty. Other captains, therefore, rather than spare a penny, will suffer their soldiers to starve, as is daily seen in this kingdom.

Another reason is, that supplies come so short, and so long after they are due, verifying the old proverb, “Whiles the grass grows the horse starves”. The victuals are many times corrupted, as is thought, by the provant-masters, that go to the heap for cheap. And so with the purveyors of the apparel – often a suit valued at 40s proves not worth half, yet is the soldier constrained to take it, some six or nine months after it is due, at the charge of the captain for transporting from place to place. Most part of the army, therefore, seem beggarly ghosts, fitter for their graves than to fight a prince’s battle. The report hereof so works in men’s minds that they had as life go to the gallows as to the Irish wars. The captains and soldiers “are constrained, upon their charges, with long attendance, to fetch by convoy their weekly lendings sometimes 30 or 40 miles”. Monthly musters are made by view of a commissary, and [the captain] is chequed “for insufficiency or not appearing”. If any soldiers die or run away before the end of the half-year’s musters, and others enter in their places, the captain is chequed for so many suits, “and so the soldiers entertained must starve for want of apparel, except the captain bear the loss of it.” These are accounted husbandry and gains for her Majesty!

The soldiers are compelled to carry muskets, which are very heavy. They should have calivers of a musket length, which will shoot further than muskets; “for muskets were first devised to encounter the heavy armed, and for defence of towns and fortresses, and not to answer so light services as these; besides the charge of powder and lead, the weight of which, together with the musket, doth clog and weary the bearer.” Why is the Irish rebel so strong, so well armed, apparelled, victualled, and moneyed? He endures no wants; he makes booty upon all parts of the kingdom, and sells back for money. In this way the same cow has been taken and sold back again four times in half a year, by which they (the rebels) have all the money of the kingdom. There is no soldier with a good sword but some Gray merchants or townsman will buy it from him. The soldier, being poor, sells it for 10s or 12s. And if excellent good it is worth commonly among the rebels 3l. or 4l. A graven murreon, bought of a poor soldier for a noble or 10s. is worth among the rebels 3l. The soldiers likewise, through necessity and penury, sell their powder at 12d. a pound, and the Gray merchants or townsmen collect it and sell it again to the traitors at 3s.

It is not the sword only, but famine, that will make them fall, as in the Desmondes’ wars and those of Connaught. It may be said the good shall perish with the bad. I hold there are very few but have deserved, both at God’s hands and her Majesty’s such a reward. The enemy spares neither friend nor foe, and as long as there is any plough going, or breeding of cattle, he will be able to make wars, except against walled towns or fortresses. The army pays for what it takes; the enemy does not. It is reported that her Majesty will receive them to grace by a pacification, - a dangerous example, considering the uncivil disposition of the nation. Youghal 2 January 1599 [possibly 1600?].

Explanations: “Dicing and wenching” is a reference to the gambling and womanising of the soldiers.

![]()

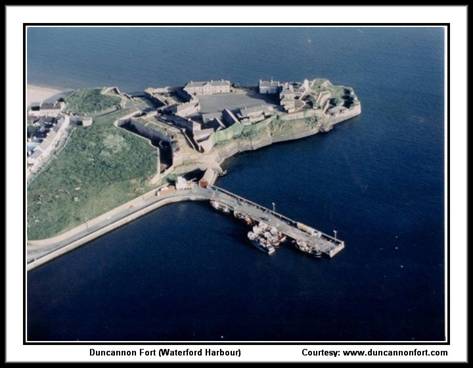

Commander Dowdall of Duncannon Fort

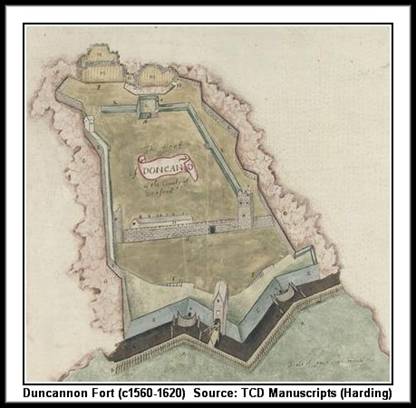

Captain Sir John Dowdall was appointed Constable or Commander of the highly strategic Duncannon Fort which guarded the entry to Waterford harbour from the Wexford side. Duncannon Fort was built in 1588 but according to legend a settlement existed there from the time of Fionn Mac Cumhaill. Due to its strategic position Duncannon Fort was centrally involved in many wars and sieges particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was captured by the Irish Confederate army under General Preston in 1645 during the Irish Confederate wars (1641-1652). It was also besieged during the unsuccessful Cromwell siege of Waterford in November 1649. In November 1590 it was reported by the Lord Deputy that Duncannon was in a weak defensive position and was manned by only twenty soldiers and an officer from Captain Dowdall’s army. A couple of years later in November 1592 Captain Dowdall wrote to Lord Burghley and informed him that he would finish the improvements to the Fort of Duncannon at a cost of four hundred pounds and would in addition supply a master gunner to help in the defence of the fort. The commandment of the Fort of Duncannon was eventually given to Captain Dowdall in September 1595 on instructions from Dublin Castle and the Earl of Ormonde. The Mayor of Waterford was instructed to supply Captain Dowdall with necessaries. He remained in command until 1601when he was succeeded as Constable of Duncannon Fort by Sir John Brockett. As events transpired Brockett ran into difficulties in August 1602 when he was accused of making counterfeit coin by Richard Dole who was a soldier in the fort. When his office was searched tools and other instruments were found. The matter was investigated and Brockett was accused of counterfeiting and melting down confiscated Spanish coin. He also had to explain the presence of “certain instruments“ in his office and also for an explanation as why did he imprison two goldsmiths in Duncannon Fort for no apparent reason. His son Lieutenant John Brockett was also implicated in the alleged counterfeiting. Sir George Carew President of Munster supported John Brockett in his defence but the whole matter was of great embarrassment to the establishment particularly as Sir John Brockett had only been knighted in August 1599. The allegations were never conclusively proven but Sir John Brockett’s position as Commander of Duncannon Fort was prematurely terminated by 1605.

![]()

Sir John Dowdall Junior inherits Pilltown Lease

Captain Sir John Dowdall Senior died in Piltown Manor, Kinsalebeg Co Waterford in 1606 and his Pilltown property was inherited by his son, also Sir John Dowdall Junior. The following is an abstract of the will of Sir John Dowdall dated 20th Nov 1604:

“Dowdall, Sir John, of Pilltown alias Ballynafoile, Parish of Kinsalebeg, Co Waterford, knight, dat. 30 Nov. 1604, proved Prerogative 29 April 1613. To wife Lady Margaret Dowdall for her maintenance and better bringing up of my younger children, the castle and manor of Pilltown alias Ballynafoile, the Raphe, Burfoye, Newtowne, Garraneasky [Garranaspic], Glystenane [Glistenane], East and West Kilmaloss [Kilmaloo], Kilmeefe [Kilmeedy], Knocbrac [Knockbrack] and Drumgollane [Drumgullane] with the hill weyre. To dau. Susanna Dowdall £300. To dau. Dorothie Dowdall £250. To dau. Johane Dowdall £200. To dau. Philippa Dowdall £200. To dau-in-law Penelope Merrick £150. To son Charles Dowdall £100 and annuity £20. To son Anthonie Dowdall £100 and £7 p.a. To son-in-law Chidley Merrick £100 from Simon Merrick deceased. To brother Jerome £10. To sister Margaret ffisher [Fisher] £10. To eldest son John Dowdall all my lands and he to be executor. Overseers: my wife, John Woods of North Tawton, Tawton, Devon, Mr. Roger Collins of same and Mr. Thomas Sherren, Vicar of Kinsale Beg. Wits: John Sparke: Thos Shevrin (sic). Codicil (undated): due unto me from my brother Dawlin £10. My son-in-law John Allen oweth me £50.”

![]()

Pilltown Sub-Leased to Richard Boyle (1620)

Sir John Dowdall Jun, who had been knighted in 1618, sold the lease of Pilltown Manor to Richard Boyle Earl of Cork in 1620 for 1700 pounds – the actual assignment from Dowdall to Richard Boyle was dated 23rd June 1626. This transaction was a transfer of the leasehold of the property and the freehold remained with Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior. The Pilltown Manor lease from Dowdall to Boyle was in fact for two hundred pounds more than the fifteen hundred pounds Richard Boyle paid Sir Walter Raleigh for the purchase of entire 42,000 acres of the Raleigh estate in 1602 – highlighting the debt written position of the Raleigh estate. The only Irish property which Raleigh maintained an interest in was the Castle at Inchiquin, which Raleigh had leased for life to the long lived Countess of Desmond. Inchiquin Castle and lands were granted to Sir Walter Raleigh when the Desmond estate was confiscated after the Desmond Rebellion. Sir Walter Raleigh leased the castle back to The Countess of Desmond for life, no doubt with the expectation that this would be a relatively short lease period as the Countess Desmond was a very old woman at the time of the lease arrangement. However the Countess had no plans to depart this life anytime soon and was still alive in 1602 when Sir Walter Raleigh sold his Irish estates to Richard Boyle.

Sir Richard Boyle’s desire for property and land knew no bounds and compassion or chivalry were certainly traits that were not going to get in his way where land or property ownership was involved. He proceeded to institute eviction proceedings against the impoverished old Countess of Desmond who was not going to concede without a fight despite her age which at the time was by all accounts somewhere between 120 and 140 years of age! As the story goes the Countess set off for London in 1604 to present her case against eviction to the then King of England James I. She set sail for Bristol and then walked from Bristol to London accompanied by her 90 year old invalid daughter where her petition to be allowed to remain in the Castle of Inchiquin was presented to King James I. Unfortunately the old Countess died in Inchiquin later in 1604 at the extraordinary alleged age of 140 years (her age is disputed but is generally accepted to have been between 120 and 140 years of age!). She died when she apparently fell from either a cherry tree or nut tree in her garden in Inchiquin! In any case Sir Richard Boyle did not come out of the situation smelling of roses after his greedy campaign to evict the Countess from her home at such an advanced age.

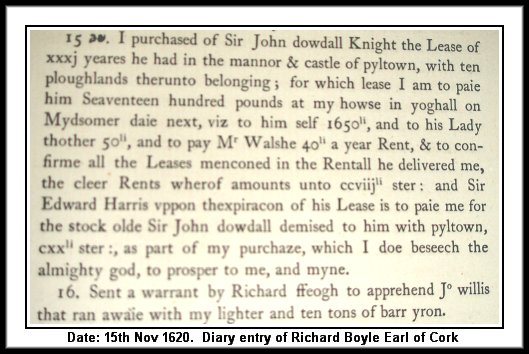

The following are notes from Richard Boyles relating to the purchase of the lease of the manor of Pilltown and lands from Sir John Dowdall Jun as recorded in the Lismore papers.

Date 1st January 1620: “I ow to Sir John Dowdall for the purchase of the lease of xxxi years in the mannor of piltown: 1700li. Paid heer of 50li. Paid also 1650li, in all 1700 li ster.”

Date 23rd January 1620: “Sir John Dowdall perfected to me my assurance of the castle town & Lands of piltown etc, and refused to accept the 650li I tendered him, but made choice rather to be paid that some, and thither thowsand pounds all entirely (for the the purchaze of Sir Anthony Awchers lands in the County of Lymerick) on St Thomas daye next: for payment of the whole that day being 1650li, I gave him my own bond, and a clause of Reentry.”

Date 29th January 1620: “I paid Sir John Dowdall lxxxij li. X3 ster: in gold for the forbearance of 1650li, that i was to paie him for Piltown on St Thomas day next, in regard he should forbear yt 6 moneths from that daye for ten in the C.th to be also then paid with the princepall.”

Date: 15th November 1620: The following entry in the Lismore papers diary of Richard Boyle the Earl of Cork confirms his purchase of the lease of Pilltown from Sir John Dowdall in 1620 for 1650 pounds sterling. Dowdall would have been leasing the land from the Walshs of Pilltown who owned most of Kinsalebeg at that time and this transaction was a transfer of the lease from Dowdall to Boyle. The diary entry confirms that Mr Walshe was to be paid forty pounds sterling a year in rent as part of the arrangement and we assume that this was a reference to Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior. It would appear that the Earl of Cork was quite happy to refer to Sir John Dowdall Knight by his full title but seemed unable to bring himself to refer to Sir Nicholas Walsh Knight in the same manner. Relationships between the Boyles and Walshs had deteriorated after the death of Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior and of course the two families finished up on opposite sides of the 1641 rebellion. This particular diary entry indicates that the lease included Pilltown Castle as well as Pilltown Manor and about a thousand acres of land. This is one of the few occasions where Pilltown Castle was mentioned in any lease arrangement. The next entry in the diary dated the 16th November 1620, the day after the above lease, the Earl of Cork obviously ran into a problem when a certain Joseph Willis apparently stole a boat belonging to him with ten tons of iron on board.

Date: 7th April 1622: ”I received from Sir John Dowdall, the deeds of Monodross rout 8 acres in the mannor of piltown, from Mannsfeyld to Bluett, from Bluett to Reyly, from Reyly to ould John Dowdall, which yong Sir John conveighed to me, and my heires forever.”

Date: 23rd June 1626: An indenture or assignment or lease between Sir John Dowdall Jun, Richard Boyle (Earl of Cork) was drawn up in June 1626 according to manuscript MS 43, 785/2 of the Lismore Papers in the National Library. This document is very difficult to read which is not surprising considering it is almost four hundred years old but it essentially details the transfer of the lease of land and property in the Pilltown area from Sir John Dowdall Junior to the Earl of Cork. It references Sir Nicholas Walsh who would have been the actual owner of the estate at that time. It refers to the land & property in Pilltown as being the Manor of Pilltown and the lands in the parish of Kingsale [Kinsalebeg] County Waterford. It would appear that the land involved was more than just Pilltown as it refers to Pilltown, Glistinane, Rath, Knockbrack, Monatray, Ballysallagh, Kilmalloo and other townlands. It also refers to the presence of “the mill of Pilltown” which seems to confirm the existence of a mill in Pilltown as far back as the early 1600s.

The Lismore Papers also outline that in 1622 Sir John Dowdall Junior was to pay Sir Anthony Awcher (Ager or Aucher) 2800li for the purchase of Castletown in Limerick. Sir John Dowdall Jun died in 1641 when he was ambushed on his way to the defence of Newcastlewest in the 1641-1649 rebellion. At that time the Dowdalls were in possession of Kilfinny Castle in Limerick and Lady Dowdall organised the defence of the castle against four separate rebel attacks before eventually being forced to surrender. Castletown was later to come into the ownership of the Wallers when Elizabeth Dowdall, widow of Sir John Dowdall Jun, married Sir Hardress Waller a Cromwellian soldier who was born around 1604 in Castletown Limerick. Hardress Waller was one of the judges at trial of King Charles I and Waller was later convicted of regicide. He was sentenced to be executed but managed to escape execution and died in prison. Sir Hardress Waller (c. 1604-1666) and Elizabeth Dowdall had four daughters Elizabeth, Anne, Mary and Bridget. Their eldest daughter Elizabeth Waller (c. 1636-1708) married firstly Sir Maurice Fenton (c. 1622-1664) of Mitchelstown and secondly Sir William Petty (c. 1623-1687) who was an English economist, scientist and philosopher. Sir William Petty became very well known in Ireland when he served under Oliver Cromwell as physician-general in 1652. At that time he was Professor of Anatomy in Brasenose College, Oxford and was also a Professor of Music in London. He took a career break in 1652 to embark on a most unlikely journey as part of Cromwell’s army to Ireland – no doubt his medical experience was of great benefit but it is unlikely that he had many opportunities to be involved in music sessions on his travels. In Ireland he was involved in the surveying of land that was confiscated after the 1641-1649 rebellion and distributed mainly to Cromwell’s soldiers. He was responsible for the Civil Survey in 1655 to 1656 which was a major mapping exercise of land in Ireland and was used as an important source of information for the confiscation and re-distribution of land during the Cromwellian settlements. The Civil Survey or the Down Survey as it is more commonly known is still used as an important source of information regarding land ownership in the 17th century and the maps produced as a result of the survey were probably the most advanced maps of any country produced up to that point. As an award for his services he received 30,000 acres of land around Kenmare in Kerry. Sir William Petty returned to England and went on to become an MP in England and was knighted in 1661. He was a founder member of The Royal Society and the focus of his work after his knighthood was economics and the social sciences. He came back to Ireland in 1666 and produced many reports on how to improve Ireland’s economy. He helped found the Dublin Society and returned to London in 1685, where he died two years later in 1687. Elizabeth Petty nee Waller or Lady Petty, the daughter of Sir Hardress Waller and Elizabeth Dowdall (widow of Sir John Dowdall of Pilltown Manor) and wife of Sir William Petty, was made the first Baroness Shelburne in 1688 the year after her husband’s death. Her eldest son Charles Petty (c. 1673-1696) was elevated to the peerage as Baron Shelburne on the same day as his mother became Baroness Shelburne. The other children of Sir William Petty and Elizabeth Waller were John Petty (c. 1669-167), Anne Petty (c. 1671-1737) and Henry Petty (1675-1751) Earl of Shelburne. A granddaughter of Sir William Petty, namely Anne Petty daughter of Henry Petty Earl of Shelburne, was later to marry Francis Squire Bernard of Castle Bernard in Bandon Co Cork. Francis Squire Bernard was a major landowner in Kinsalebeg in the 18th century as outlined elsewhere in this history.

It would appear from Sir Richard Boyle’s notes in the Lismore Papers that the occupation or lease of Pilltown Manor before 1600 went from Mannsfeyld [Mansfield] to Bluett to Reyly [Reilly] and then to Sir John Dowdall Snr sometime possibly around 1590. Sir John Dowdall Jun then inherited the lease of Pilltown Manor lease until he sold the lease to Sir Richard Boyle Earl of Cork in 1620. The Earl of Cork appeared to be still leasing Pilltown Manor and other lands in the Kinsalebeg area from the Walsh family at the time of the Civil List around 1654. According to a 1641 deposition from a William Beale of Kinsalebeg, the nearby Castle of Pilltown was besieged in Jan 1641 or Jan 1642 by Sir Nicholas Walsh, his son James, various others and three or four hundred armed men. The siege went on until April (1641 or 1642). It would appear therefore that the Walshs were not in control of Pilltown Castle itself at that point and were trying to reclaim it. William Beale, a yeoman, who was employed by Sir Philip Percival according to his own statement, was obviously in Pilltown Castle at the time of the rebel attack in 1641/1642 but it is not clear if he was the main resident. Sir Philip Percival had over 100,000 acres of land in Ireland in 1641 and may well have had control of the castle but there is no clear indication of this. From this period onwards any references to Pilltown Manor and Pilltown Castle seemed to be in connection with the Walshs of Pilltown. The Walshs eventually sold most of their extensive Kinsalebeg land and property holdings including Pilltown to Francis Bernard of Bandon and the Earl of Grandison in the 1720s. In the 19th century the house and land that constituted the former Manor of Pilltown came into the ownership of the Kennedy family. At the time of Griffiths Valuation around 1850 the house and land of the former Pilltown Manor was being leased by Declan Tracy from the representatives of the Sir J. Kennedy. At the time of the 1901/1911 census the house and farm was owned by Maurice Doyle whose son Willie Doyle became the first Captain of the Kinsalebeg Volunteers in 1913. The house was demolished in the 1950s but at that time it was very much a skeleton of the original elaborate defensive structure that had existed in earlier centuries.

![]()

Follow

Follow