History of Kinsalebeg

The Great Famine

Introduction

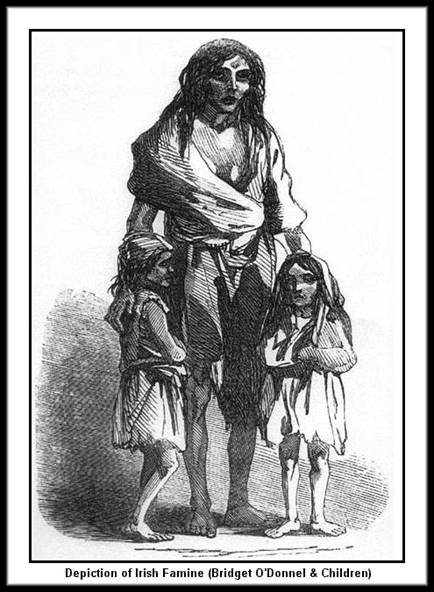

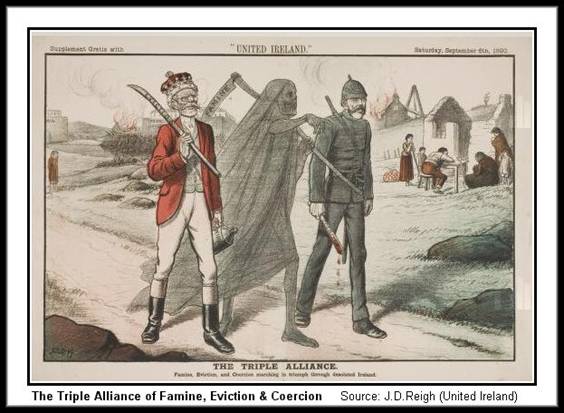

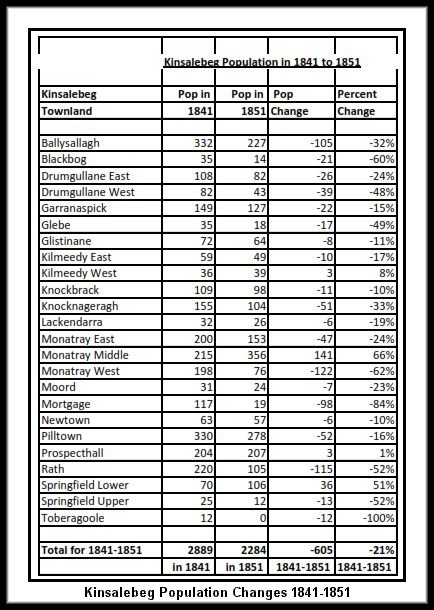

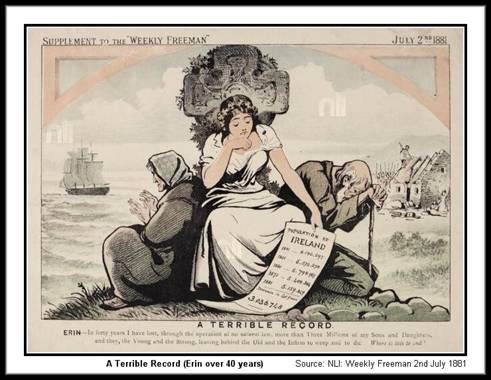

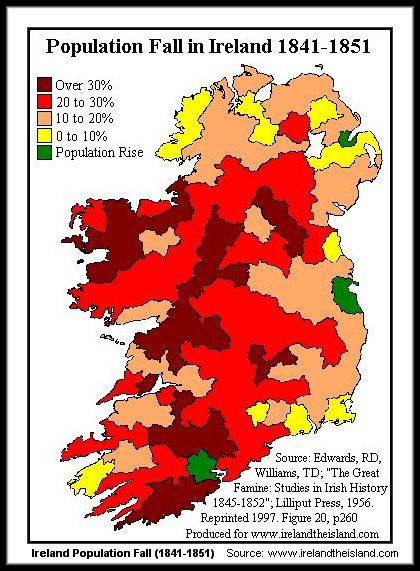

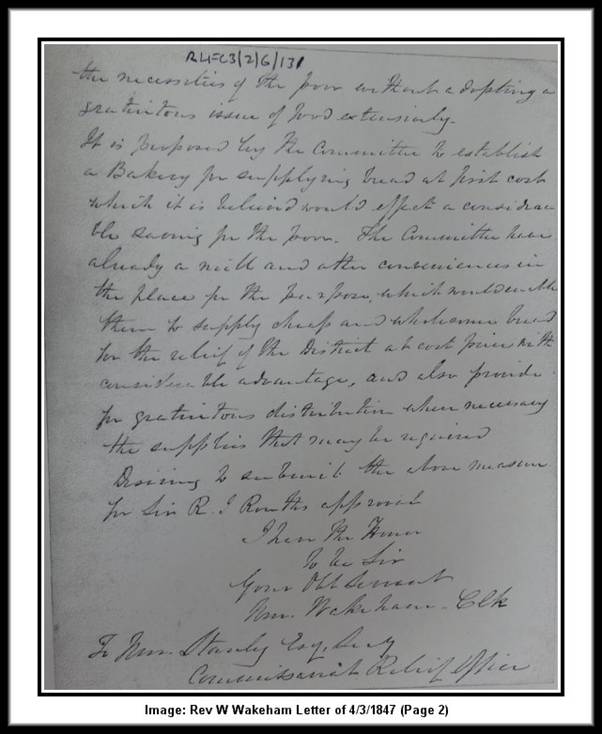

The cause and effects of The Great Famine in the 1845-1851 period in Ireland are well documented and we are not going to cover these details here. We will attempt to establish a picture of the situation in Kinsalebeg at that period in terms of population changes, famine relief efforts and details of some of the individuals and institutions involved at the time. It is very difficult to establish exactly the casualties and emigration figures for Kinsalebeg parish during the famine as there are very little detailed parish statistics available other than the overall population changes as recorded in the census of 1841 and 1851 - if we can rely on their accuracy. What is clear is that the population of 2889 people in Kinsalebeg in 1841 was the highest population ever recorded for Kinsalebeg before or since the famine. This population had decreased to 2284 people in 1851 – a decrease of 605 people or 21% in the ten year period caused by a combination of factors including famine deaths, emigration and population movements to workhouses or nearby towns. We will cover the 1845-51 famine period in greater detail below but we should firstly mention that whilst the 1845-51 famine was devastating it was not of course the first famine in Ireland and in reality there were very few decades in Ireland between 1500 and 1900 when there was not a famine of some description resulting from war, crop failures, pestilence, scorched earth policies or a combination of these. The following are details of just two of these famines in the 16th and 18th century respectively which were also devastating in their effect.

![]()

Famine of 1579-1590 Period

The Desmond rebellions in the decades before 1590 were a particularly devastating period in the history of Munster. Sir Warham St Leger had been involved in a bitter military campaign against the Desmond led Irish rebels for over a decade. He was then appointed provost-marshal of Munster in 1579 and proceeded to implement a scorched earth policy over the next three years. This resulted in a severe famine in Munster and, aside from the deaths in the fighting itself, Sir Warham St Leger estimated in April 1582 that in the previous six months alone 30,000 people had died of famine. The fighting, famine and plague continued until 1589 by which time it has been estimated that one third of the population of Munster had died. Historians and poets of the period give the same picture and it is apparent that it was possible to travel for miles outside the cities of Munster without meeting man, woman, child or beast. There are two well known accounts of the devastation resulting from the Desmond rebellions which are worth recounting. The first is a Gaelic account in the Annals of the Four Masters5:

“... the whole tract of country from Waterford to Lothra, and from Cnamhchoill to the county of Kilkenny, was suffered to remain one surface of weeds and waste... At this period it was commonly said, that the lowing of a cow, or the whistle of the ploughboy, could scarcely be heard from Dun-Caoin to Cashel in Munster”.

` A second account of this devastating period was given by the poet Edmund Spenser in 1596 in a pamphlet titled A View of the Present State of Ireland6. Spenser was well familiar with the area around Youghal and Kinsalebeg having spent a period in the company of his fellow colonist Sir Walter Raleigh in Youghal. A View of the Present State of Ireland was written by Spenser in 1596 and was in the form of a conversation between two individuals, presumably because Spenser was not brave enough to give his own views directly. It was not actually published until the middle of the following century due to the inflammatory tone of the article which basically outlined that Ireland would never be brought under control until its language, customs, culture and religion were obliterated by violence if necessary. However despite the vitriolic nature of Spenser’s diatribe against the Irish there is no reason to disbelieve his following picture of the state of Munster in 1596:

“In those late wars in Munster; for notwithstanding that the same was a most rich and plentiful country, full of corn and cattle, that you would have thought they could have been able to stand long, yet ere one year and a half they were brought to such wretchedness, as that any stony heart would have rued the same. Out of every corner of the wood and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked Anatomies [of] death, they spoke like ghosts, crying out of their graves; they did eat of the carrions, happy where they could find them, yea, and one another soon after, in so much as the very carcasses they spared not to scrape out of their graves; and if they found a plot of water-cresses or shamrocks, there they flocked as to a feast for the time, yet not able long to continue therewithal; that in a short space there were none almost left, and a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast”.

![]()

Famine of 1740-1741 Period

The following is a description of the 1740-41 famine as outlined in “The History of the Great Irish Famine of 1847 with Notices of Earlier Irish Famines3”:

“Irish Famine 1740-41: But a terrible visitation was at the threshold of Celt and Saxon in Ireland; the Famine of 1740 and '41. There were several years of dearth, more or less severe between 1720 and 1740. "The years 1725, 1726, 1727, and 1728 presented scenes of wretchedness unparalleled in the annals of any civilized nation," says a writer in the Gentleman's Magazine. A pamphlet published in 1740 deplores the emigration which was going forward as the joint effect of bad harvests and want of tillage: "We have had," says the author, "twelve bad harvests with slight intermission." To find a parallel for the dreadful famine which commenced in 1740, we must go back to the close of the war with the Desmonds [1589]. Previous to 1740 the custom of placing potatoes in pits dug in the earth, was unknown in Ireland. When the stems were withered, the farmer put additional earth on the potatoes in the beds where they grew, in which condition they remained till towards Christmas, when they were dug out and stored. An intensely severe frost set in about the middle of December, 1739, whilst the potatoes were yet in this condition, or probably before they had got additional covering. There is a tradition in some parts of the South that this frost penetrated nine inches into the earth the first night it made its appearance. It was preceded by very severe weather. "In the beginning of November, 1739, the weather," says O'Halloran, "was very cold, the wind blowing from the north east, and this was succeeded by the severest frost known in the memory of man, which entirely destroyed the potatoes, the chief support of the poor." It is known to tradition as the "great frost," the "hard frost," the "black frost," etc. Besides the destruction of the potato crop it produced other surprising effects; all the great rivers of the country were so frozen over that they became so many highways for traffic; tents were erected upon the ice, and large assemblies congregated upon it for various purposes. The turnips were destroyed in most places, but the parsnips survived. The destruction of shrubs and trees was immense, the frost making havoc equally of the hardy furze and the lordly oak; it killed birds of almost every kind, it even killed the shrimps of Irishtown Strand, near Dublin, so that there was no supply of them at market for many years from that famous shrimp ground. Towards the end of the frost the wool fell off the sheep, and they died in great numbers.”

![]()

Great Irish Famine (1845-1852)

The causes of the Great Famine from 1845 onwards due to succeeding years of potato crop failure are well known and we are not going to cover these here. We are focusing mainly on the organisations and individuals involved in famine relief in the Kinsalebeg area during the famine together with some statistics on the resulting population changes in the parish.

Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee:

The Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee was formed in 1846 and for the following two years was driven by the Rev. William Wakeham, Church of Ireland curate of Kinsalebeg, who was secretary of the committee in this period. George Roch of Woodbine Hill was also actively involved and was chairman of the committee from 1846. Henry Downes Sheppard, who was married to Melian Roch daughter of the above George Roch, was treasurer of the committee. The Relief Committees came under the auspices of the Famine Relief Commission which was originally established in November 1845 in response to the failure of the potato crop and its primary function initially was to administer temporary relief to that provided by the Poor Relief (Ireland) Act of 1838. It was disbanded in August 1846 but reformed in February 1847 under the Temporary Relief Act. The revised remit of the Relief Commission, based in Dublin Castle, was to advise the government of the overall situation regarding the famine throughout Ireland and to generally oversee and co-ordinate the famine relief effort throughout the country including the distribution of Indian corn and meal. Local famine relief committees were set up around the country to implement famine relief locally. These were voluntary bodies consisting mainly of county officials, poor law guardians, local dignitaries and clergymen.

The main role of the local famine relief committees was to raise subscriptions from parishioners, to encourage local employment schemes and to distribute Indian corn from the distribution depots set up by the Relief Commission. They were also active in the feedback of information regarding the situation on the ground to the Famine Relief Commission. The Relief Commission encouraged local relief committees to publish their subscription list so as to “discourage” non-compliant landowners etc from avoiding payment or subscribing small amounts. We will see later where Lord Stuart got into difficulties in the local area for allegedly not paying a big enough subscription to the Clashmore Relief Committee even though he denied this. The main contact for the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee seemed to be Sir Randolph Routh of the Commissariat Department of the Army and his name comes up frequently in the correspondence of the Rev William Wakeham, secretary in Kinsalebeg. The Relief Commission was the main plank in the Irish famine relief program when Sir Robert Peel was the British Prime Minister. The role of public works and the poor law system assumed greater significance as time went on and the role of the Relief Commission was no longer central to the national famine relief effort. This was mainly as a result of the election of a Whig/Liberal government in Britain in July 1846 with Lord John Russell as British Prime Minister and a change in policy on the famine relief effort.

Society of Friends Auxiliary Committee:

The Society of Friends, more commonly known as Quakers, established a Central Relief Committee on 13th November 1846 to co-ordinate the Quaker famine relief effort around the country. The total Quaker community in Ireland at the time of the famine was around 3000 people and was equivalent to the population of Kinsalebeg at that time. However the influence of this relatively small Christian group on the famine relief effort in Ireland was considerable considering their size. The Quaker Central Relief Committee was responsible for the distribution of £198,326 in food and aid in Ireland between November 1846 and July 1852. The donations they raised were in the form of money, food, clothing and equipment with the bulk of the food donations coming from America in the form of Indian corn. In today’s terms £198,326 would be worth in the order of Euro 180 million which if we assume a Quaker population of 3000 in 1846 meant that the Irish Quakers contributed an average of 60,000 euro per head to the Irish famine relief effort.

The Quakers had a highly developed social conscience with a history of involvement in social issues including famine relief in earlier Irish famines of 1822 and 1830-1831. They were also highly experienced in fund-raising and co-ordinating committee activities resulting from their well established business, farming and entrepreneurial skills. The Pilltown Mills in Kinsalebeg was one such business run by the Quaker Fisher family over a period of the 18th & 19th centuries and the Fishers together with other local Quakers played a big role in famine relief in the West Waterford & East Cork area. The Quaker Central Relief Committee established four Auxiliary Committees in Waterford, Cork, Clonmel and Limerick. The Cork Auxiliary Committee incorporated the counties of Cork and Kerry (excluding baronies of Clanmaurice and Iraghticonnor) and also included the two Waterford baronies of Coshmore & Coshbride and Decies within Drum which incorporated Kinsalebeg. One of the Cork Auxiliary Committee members was Abraham Fisher of Pilltown & Youghal and the rest of the committee was made up of Thomas Harvey (Youghal), Abraham Beale, Ebenezer Pike, William Harvey, Joseph Harvey, Joshua Beale and Thomas Wright. Activities of the relief committee in Kinsalebeg included the provision of soup kitchens, corn and equipment in the form of boilers etc. The Society of Friends published a very detailed account of their famine relief activities in Ireland in 1852 in a publication titled “Transactions of The Society of Friends During The Famine in Ireland4 “ which was re-published by De Burca in 1996.

Dungarvan and Youghal Workhouses:

The workhouses of Dungarvan and Youghal were other institutions involved in famine relief of Kinsalebeg parishioners. Workhouses were essentially in house famine relief institutions in which the very poor were housed and fed in return for work of some nature such as road repairs. Once they entered the workhouse, people had to wear a uniform and were given a very basic diet. The main food they were given was stirabout which was similar to a weak oatmeal porridge. Families were split up once inside the workhouse with men, women and children generally staying in different parts of the building. The Irish hated the workhouses but the sheer magnitude of the famine forced hundreds of thousands of people to enter the workhouses to give themselves a chance of survival. It was in many cases choosing between the “devil and the deep blue sea” as the workhouses themselves were the source of much disease and death.

The location of Kinsalebeg with its proximity to Youghal meant that it came under the influence of both Dungarvan & Youghal workhouses at different periods. An 1838 Poor Law act had established 130 Poor Law Unions in Ireland which were in effect administrative units for implementing relief schemes for the destitute and the poor of the country. Each Poor Law Union was required to build a workhouse which was run by a Board of Guardians comprising of elected officials and local Justices of the Peace. The workhouses were financed by a Poor Rate which was a form of taxation which the Board of Guardians were entitled to impose in order to fund their operations. The Dungarvan Poor Law Union (DPLU) was set up in 1839 and it covered a population of around 60,000 people based on the population figures from the 1831 census. The electoral divisions within Dungarvan Union were comprised of Aglish (pop 4,762), Ardmore (7,407), Ballylaneen (3,835), Clashmore (3,386), Colligan (1,009), Dungarvan East & West (16,028), East Modeligo (592), Fews (1,247), Grange (1,874), Kilgobinet (2,364), Kilrossanty (3,119), Kinsalebeg (pop 3170), Seskinane (2,162), Stradbally (3,398) and Whitechurch (3,176). The operation of the workhouse in Dungaravan is covered in detail on the website of the Waterford County Museum7. In November 1848 it was decided to build a workhouse in Youghal and that Kinsalebeg, Grange and Ardmore would be come under the auspices of the Youghal Union.

![]()

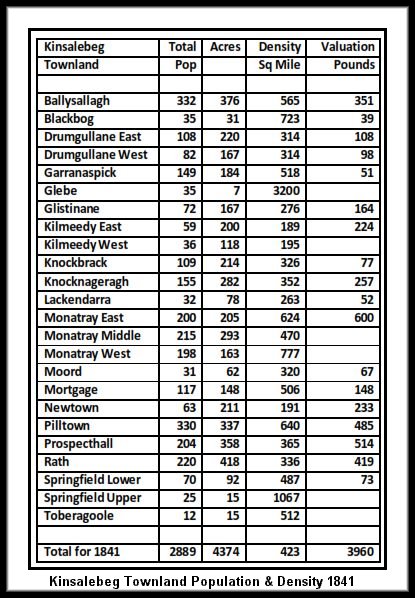

Population of Kinsalebeg in 1841

The following is an overview of the population in the Kinsalebeg area in 1841 preceding the Great Famine. This data is also replicated in the chapter on population changes in Kinsalebeg. We have tried to be consistent with the boundaries of Kinsalebeg from section to section as particular townlands were part of Kinsalebeg in some periods and appeared in nearby parishes in other periods. The period we are looking at covers 1841 to 1851 because these are the two years on which a census was done and it enables us to have a look at the population changes during the famine period.

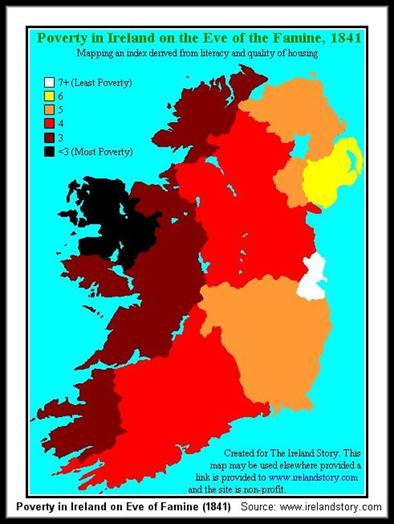

The population of Kinsalebeg was 2889 people in 1841. This was the highest population recorded for Kinsalebeg at any time in its history and compares with a population of less than 500 in 2006. The population density of Kinsalebeg in 1841 was approximately 423 people per square mile. This is an extremely high population density even for that period when the population of Ireland was at its highest. The average rural population density (ie excluding cities and large towns) for the whole of Ireland in 1841 was around 236 people per square mile and this was the approximate average rural population density for Munster also. The average rural population density in Waterford at the time was around 240 people per square mile which is slightly above the national average. The population density of the Barony of Decies within Drum, within which Kinsalebeg is located, was 289 people per square mile in 1841 which is over 20% higher than the average rural population in Waterford and the rest of Ireland.

Comparing the above rural population density figures with those of Kinsalebeg in 1841 indicates that the rural population density of Kinsalebeg was considerably higher than averages for Waterford and the rest of Ireland. Any townland population density of over 400 persons per square mile would have been considered over populated at the time and Kinsalebeg had alone had around twelve townlands with a population density in excess of 400 and indeed the average for the parish as a whole was 423 which in itself was a very high population density. It is estimated that there were just over 200 rural townlands in Waterford with population densities in excess of 400 persons per square mile in 1841 and of these around fifty or 25% were in the Barony of Decies within Drum where Kinsalebeg was situated. In addition about twelve or 25% of these Decies within Drum over populated townlands were in Kinsalebeg. Kinsalebeg appeared to be a popular place to live in 1841.

![]()

Kinsalebeg Townland Population Summary in 1841

The following table is a summary of the population statistics for each townland of Kinsalebeg in 1841. The “Total pop” column is the total population of each townland of Kinsalebeg in 1841, “Acres” is the total rounded acreage of each townland and “Density Sq Mile” is the density of population per square mile for that townland. The “Valuation Pounds” is not really relevant here and is just the rounded rateable valuation for that townland in 1841. Some of the density figures such as those for Glebe (3200) and Springfield Upper (1067) are not included in the overall averages as they refer to small areas (15 acres or less). The individual figures for acres and valuation have been rounded up for convenience so totals at bottom are slightly different. The overall population of the parish was 2889 spread over 4374 acres giving an average population density of 423 people per square mile or just over 1.5 persons per acre.

If we look at the above table we see that within Kinsalebeg itself there are townlands with much higher densities than the Kinsalebeg average of 423 people per square mile. Monatray West had a population density of 777 per square mile, Pilltown was 640 per square mile, Ballysallagh was 565 per square mile, Garranaspick was 518 per square mile and Springfield Upper had a density of 1066 per square mile. These figures indicate very high population densities particularly in areas close to the sea like Monatray West, Ballysallagh and Shanacoole where fishing was intensive in addition to agriculture. Pilltown was also a high density population area and could be viewed as the “industrial centre” of Kinsalebeg with its involvement in milling etc. Some nearby parishes such as Ringnagonagh, Clashmore and Aglish also had high population densities in 1841 with Ringnagonagh the only parish of this group with a higher population density than Kinsalebeg. The population in Grange, Ardmore and Ballymacart was also quite high at that time but was spread over a relatively large area so the density was not so high.

Summary of rural population density per square mile in 1841:

- Average in rural Ireland including Ulster: 236 people per square mile

- Average in rural Munster: 237 people per square mile

- Average in rural Waterford: 240 people per square mile

- Average in Decies within Drum barony: 288 people per square mile

- Average in Kinsalebeg parish: 423 people per square mile

- Average in Ballysallagh townland: 565 people per square mile

- Average in Pilltown townland: 640 people per square mile

- Average in Monatray West townland: 777 people per square mile

- Average in Ballyheeny parish: 322 people per square mile

![]()

Population Changes in Kinsalebeg during the Famine (1841-1851)

The population of Kinsalebeg decreased from 2889 to 2284 between 1841 and 1851 according to the available census information for 1841 and 1851. This was a decrease of 605 inhabitants or approximately 21% over the ten years. This was the lowest decrease in nearby parishes with Clashmore decreasing by 25% (2414 to 1820), Ballyheeny decreasing by 22% (1720 to 1335), Ardmore decreasing by 29% (4044 to 2886), Grange decreasing by 32% (1587 to 1077), Glenwilliam decreasing by 40% (1079 to 647) and Grallagh decreasing by 39% (1284 to 789). Templemichael parish had the largest decrease of the nearby rural parishes with a 45% population decrease (2994 to 1645). The average population decrease in the rural parishes surrounding Kinsalebeg was just over 30% and Kinsalebeg at 21% was the lowest decrease of all the parishes in the vicinity.

The population fluctuations in Kinsalebeg between 1841 and 1851 vary significantly from townland to townland as we can see from the table below. Springfield Lower actually shows a population increase of 51% (70 to 106) and at the other end of the scale Mortgage shows a decrease of 84% (117 to 19). Monatray Middle actually shows a population increase of 66% but we believe this is a mistake in the census as Monatray West shows a decrease of 62%. It would appear that some of the census figures for the Monatary West jury finished up in the Monatray Middle and possibly East townlands so it may be better to treat the whole of Monatray as one entity for comparison purposes.

The Kinsalebeg population decrease was roughly in line with the population decrease in the rural areas of Waterford which decreased by 20% (172,971 to 138,754) between 1841 and 1851. The population of Waterford City actually increased by 9% in this period (23,216 to 25,297) and the overall population of the whole county of Waterford decreased by 16% (196,187 to 164,051) which compares with the 32 county average of a 20% population decrease (8,175,233 to 6,552,115). The 1841 to 1851 decade covers the main part of the famine period even though the famine and population decline really went on for a number of years after 1851. The population decreases in Kinsalebeg and surrounding areas and indeed in the whole of Ireland are only partially accounted for by famine deaths. There was a significant amount of emigration during this period and there was also population movement of people to local towns and workhouses particularly Dungarvan and Youghal.

It is virtually impossible to estimate the famine mortality rate in Kinsalebeg or indeed any other part of the country. The first thing to come under the microscope would be the accuracy of both the 1841 and 1851 census figures. If we assume the census figures are accurate then we would have to factor in what would have been the likely natural increase/decrease in the population of Kinsalebeg outside of the famine completely – all indications were that the population was increasing in the period leading up to the famine. The next factor would be to calculate what the level of emigration was in the period 1841-1851 and we have no accurate way of calculating this. We do know however that temporary or permanent emigration from West Waterford was well established before the famine particularly with the development of the fishing industry in Newfoundland, which involved in the main families from Waterford and south east area. The third factor would be an estimation of the number of people from Kinsalebeg who finished up in the workhouses in Youghal and Dungarvan and again there are little or no statistics for this.

The last contributory factor to population change in the period would be of course the actual natural deaths during the period. Joel Mokyr2 in his 1983 analysis of the effect of the famine came up with some statistics on the likely mortality rates in that period. Using his figures we could estimate that the mortality rate in Kinsalebeg would have been on average around 25 deaths per 1000 of population during the famine period. If we round up the population of Kinsalebeg to 3000 at the start of the famine then this would give a figure of around 75 deaths in Kinsalebeg caused by the famine. These figures appear quite low but it is generally acknowledged that Mokyr’s figures are the most accurate estimates to date of actual mortality rates resulting from the famine. The comments of Rev William Wakeham, curate of Kinsalebeg, in a letter to the Famine Relief Commission in January 1847 indicates that up to that time Kinsalebeg:

“has been to the present time preserved from the calamity of deaths arising from starvation”.

According to Rev Wakeham this was in the main due to the very effective famine relief program being run by the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee. The population decline in Kinsalebeg continued unabated after the famine with a decline of 24.47% in the period 1851-1861 and a decline of 20.64% in the period 1861-1871 alone which was predominantly due to emigration from the area.

The Famine Relief Commission

The Relief Commission was set up by the Government in November 1845 under the responsibility of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Its primary function was to collate information nationally about food shortages resulting from potato crop failures, to monitor the level of distress of the poor and destitute, to provide relief and instructions to the local famine relief committees and to oversee the establishment of local food depots holding typically Indian corn and meal. The local relief committees could purchase food from these depots sometimes at cost price as the overall price of corn varied enormously during this period due to demand and shortages. Exporting of corn was a very attractive option during this period as prices were very good and it was an ongoing struggle to ensure that a sufficient quantity of corn was retained in Ireland for local consumption. Unfortunately, the exporting of corn from Ireland continued unabated during the famine period with consequent disastrous results. Indeed the bulk of the corn available from food depots for local distribution was the cheaper imported Indian corn. The head of the famine Relief Commission at Dublin Castle was Sir Randolph J. Routh whose title was Commissary-General and the secretary of the Relief Commission was Sir William Stanley and both of these are referenced in communications between the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee and the national Relief Commission in Dublin Castle.

The local famine relief committees were typically set up at parish level and typically involved local landlords, clergy, magistrates, business leaders, constabulary and Poor Law guardians. The chairman of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee was George Roch and the secretary was Rev William Wakeham who was the Church of Ireland curate of Kinsalebeg at that time. The treasurer was H D Sheppard up to March 1847 but William Wakeham appears to have taken over the role of treasurer in April 1847 as indicated in his last letter to the Relief Commission. The local famine relief committees raised funds by subscriptions in the local area and the list of subscribers had to be published and was also generally forwarded to Dublin Castle. The Relief Commission generally subscribed additional funds to the local relief committees of up to half the amount of money raised locally. We include in this chapter some of the correspondence between the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee and the national Relief Commission in Dublin Castle.

Famine Relief Commission Papers 1845-1847

The following are details of Famine Relief papers containing correspondence between the Famine Relief Committee in Dublin and Kinsalebeg in the 1845-1847 period:

Location: National Archives Dublin

File Reference: RLFC 3/2/29/12

Description: Reverend William Wakeham was curate of Kinsalebeg and secretary of the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee in the 1845-1847 period. This particular famine relief file in the National Archives contains ten items which are mainly correspondence between Rev William Wakeham of Kinsalebeg and the Famine Relief Committee which was set up to coordinate famine relief nationally. It includes requests for instructions on how to apply for government assistance and describing the work being done by the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee. It also includes a certified list of subscribers to the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee with a note attached stating “The Kinsalebeg committee has not been returned by Lord Stuart de Decies”. Lord Stuart was Lieutenant of Waterford at that time. Rev Wakeham acknowledges that the grant of £153 would be paid if the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee agreed to abide by the government’s rules governing the distribution of relief. He argues however that the committee should be permitted to sell food at a subsidised rate, which they had been doing up to this point, and he forwards a copy of the committee resolutions which supported this position. In a subsequent letter Rev Wakeham forwards a further certified list of subscribers to the relief committee. He also requested a soup boiler as one of those in use by the Kinsalebeg committee was in poor condition. He also confirms that the £20 received from the Quaker Society of Friends association and all other contributions received by the committee were cash donations.

Note re Lord Stuart de Decies: Henry Villiers-Stuart of nearby Dromana had caused controversy in both Ireland and the British Parliament in 1826 when he was elected to the British Parliament in the cause of Catholic Emancipation. Henry Villiers-Stuart lost his seat as MP at the general election of 1830 but was appointed as Lieutenant of the City and County of Waterford in 1831 and was still in this position at the time of the famine. The position of Lieutenant of a county was based on the English model and was introduced into Ireland in place of the old Irish position of county governor. The governorship of County Waterford had previously belonged to Dromana in 1766. In 1839 he was created a baron of the United Kingdom, as Lord Stuart de Decies, but was still Lieutenant of Waterford at the time of the famine.

![]()

Famine Relief & Rev William Wakeham

Rev William Wakeham was a Church of Ireland curate at Kinsalebeg in the period 1840 to 1847 and was Secretary of Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee up to 1847. George Roch of Woodbine Hill was Chairman of the Famine Relief Committee at this time and the Church of Ireland overall played a significant role in the whole area of famine relief in Kinsalebeg. The role of famine relief was carried out without regard for the religion of the needy, which to a great extent was among the Catholic parishioners. It should also be said that the Quaker community in Kinsalebe, led by the Fisher family of Pilltown, also played a big role in famine relief in this period.

William Wakeham played a major part in minimising the effects of the famine in the Kinsalebeg area. He was a tireless worker in the whole area of famine relief with his involvement in fund raising and provision of food to the hungry and destitute in the parish during a very difficult period. We have outlined elsewhere that there was quite a large population of just under 3000 people in Kinsalebeg parish at this time so the whole area of famine relief was a major undertaking. William Wakeham died at the age of 32 in June 1847 as a result of a fever and his table tomb stone in the northwest corner of the graveyard of Kinsalebeg Church near Ferrypoint bore the inscription:

“Sacred to the memory the Rev. William Wakeham. For 7 years Curate of Kinsalebeg who died June AD 1847. He fell victim to disease brought on by his exertions in relieving the wants of the suffering poor of the parish during the memorable pestilence of the Famine. In the 33rd year of his age”

He was undoubtedly one of the heroes of Kinsalebeg over the centuries and one of the many Kinsalebeg people whose memory should not be forgotten. The following outlines some correspondence between Rev William Wakeham and the Irish Famine Relief Commission in Dublin Castle in the period 1846 to 1847. The letters give an overall picture of some of the issues at the time and some details as to how famine relief operated in Kinsalebeg.

Date 16th Dec 1846: The following is a letter from Rev William Wakeham to Mr Stanley Secretary of Irish Relief Commission in Dublin Castle in December 1846:

“Kinsalebeg

Youghal

16th Dec 1846

Sir,

As Secretary of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee I beg leave to apply for the necessary instructions for making application for government assistance in aid of the funds collected for the relief of the destitute poor of Kinsalebeg District Co. of Waterford. I beg leave to add that for last seasons relief this district was joined to the subdistrict of Clashmore from which it has been with the sanction of the Lord Lieutenant of the County, of late departed, and a committee appointed, of which his Lordship has approved.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your most obedient servant

Wm Wakeham Secy

To Mr. Stanley Esq. Secy Irish Relief Commission”.

Date: 4th January 1847: The following is a letter from Rev William Wakeham to Mr Stanley Secretary of Irish Relief Commission in Dublin Castle in January 1847. Included with the letter was a list of subscribers to the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief fund. It also indicates that in the previous week about two tons of barley meal and Indian corn was distributed to about 250 families in Kinsalebeg. It indicates that due to the presumably high cost of corn in the market they were giving corn and meal at prices up to 20% lower than cost prices to those in a position to pay. It also indicates that food was being given at no cost to those not in a position to pay either by infirmity or destitution or because the workhouse in Dungarvan was full:

“Kinsalebeg

Youghal

4th January 1847

Sir,

As Secretary of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee I beg leave to submit this accompanying list of subscriptions received by the Treasurer and to solicit a grant of the funds planned by Government at the disposal of the Commissary General Sir Randol Routh.

I beg leave to state the mode and extent of relief adopted and carried out by the Committee for the information of Sir Randol Routh.

The subscription list was opened in the month of September last and the Committee has since by a weekly distribution of Barley meal & Indian corn in quantities of from ½ stone to 2 ½ stone according to the number in family & necessity of cases afforded such aid to the really destitute poor on the Relief lists.

The Reduction below cost prices has been according to the state of the markets at 1/8th and 1/6th or 1/5th. Quantity distributed in this week is about two tons of meal amongst 250 families.

I should further beg to state it is to be expected that as the workhouse of the District of Dungarvan is reported full that gratuitous aid will have to be afforded to the infirm and those incapable of labour in return. Such relief it is proposed to give by issuing tickets for soup in those cases with gratuities of meal.

I have the Honour to be Sir

Your Obedient Servant

Wm. Wakeham

Curate of Kinsalebeg

To Sir Stanley Esq.”

Subscription list to Kinsalebeg Famine Relief fund (1847):

Attached to the above letter was a note to the Treasurer of the Kinsalebeg Relief District Committee listing the contributors to the famine relief fund. The note was dated 25th March 1847 and was signed by George Roch Chairman [of Kinsalebeg Relief Committee] and Rev Wm. Wakeham Clk Secy [Secretary] Curate of Kinsalebeg. The note was accompanied by the following list of subscribers and we assume this was the list sent with the letter of 4th January above:

List of subscribers to the Kinsalebeg Relief Fund.

Mrs Scott Smyth £30 0s 0d

His Grace the Duke of Devonshire £10 0s 0d

Peter Fisher £10 0s 0d

Declan Tracy £10 0s 0d

George Roch £5 5s 0d

The Rev H H Beamish £5 0s 0d

Mrs Jackson £5 0s 0d

Thos Feuge £5 0s 0d

Sir John Kennedy £5 0s 0d

John Green £5 0s 0d

The Rev William Wakeham £3 0s 0d

Thomas Ponsonby Carew £3 0s 0d

Charles De Valonei ? £3 0s 0d

The Rev. Michael Purcell P.P £3 0s 0d

Arthur Ussher £3 0s 0d

The Rev James Elliott £2 0s 0d

William Fudge £2 0s 0d

H.D Sheppard £2 0s 0d

Michael Kennedy £1 10s 0d

Thomas Kennedy £1 10s 0d

Richard Bayley £1 1s 0d

John Russell £1 0s 0d

Patrick Mulcahy £1 0s 0d

William Burns £1 0s 0d

Thomas Ahern £1 0s 0d

Robert Wynn £1 0s 0d

Malachy Carroll £1 0s 0d

------------

Page 1 Sub Total £121 6s 0d

Thomas Halloran £1 0s 0d

Richard Power £1 0s 0d

The Rev William Kirby R.C.C. £1 0s 0d

John Veal £1 0s 0d

Richard Power £1 0s 0d

Mrs Fitzgerald £1 0s 0d

Francis Kennedy £1 0s 0d

Alexander Kennedy £1 0s 0d

Robert Fitzgerald £1 0s 0d

John Macarthy £0 10s 0d

Thomas Keefe £0 10s 0d

William Connory £0 10s 0d

Laurence Connory £0 10s 0d

Robert Connory £0 10s 0d

Maurice Connory £0 10s 0d

Peter Donovan £0 10s 0d

John Thornton £0 10s 0d

Widow Morrisey £0 10s 0d

Patrick Connors £0 10s 0d

James Nugent £0 10s 0d

Bridget Brown £0 10s 0d

Matthew Whelan £0 10s 0d

William Mulcahy £0 10s 0d

Maurice Connory £0 10s 0d

James Curreen £0 10s 0d

John Connolly £0 10s 0d

William Curreen £0 10s 0d

Thomas Connolly £0 10s 0d

Widow Curreen £0 10s 0d

Stephen Connell £0 10s 0d

-------------

Page 2 Sub Total £141 6s 0d

Maurice Connolly £0 10s 0d

Joseph Croker £0 10s 0d

The Rev H H Beamish’s Children £0 10s 0d

Widow Kennedy £0 10s 0d

John Connors £0 10s 0d

Cornelius Connors £0 10s 0d

John Curreen £0 10s 0d

Richard Barrett £0 10s 0d

Patrick Kane £0 7s 5d

Edmund Farrell £0 7s 5d

Richard Burn £0 7s 5d

Maurice Mulcahy £0 7s 5d

John Barron £0 5s 0d

Thomas Thornton £0 5s 0d

Mayard ? Crotty £0 5s 0d

John Troy £0 5s 0d

Patrick Broderick £0 5s 0d

Thomas Brown £0 5s 0d

Patrick Hogan £0 5s 0d

Denis White £0 5s 0d

John Healy £0 5s 0d

James Curreen £0 5s 0d

Thomas Roche £0 5s 0d

John O’Brien £0 5s 0d

Widow Connory £0 5s 0d

Patrick Flynn £0 4s 0d

Patrick Brown £0 2s 5d

Patrick Flynn £0 2s 5d

William Bomster £0 2s 5d

Andrew Healy £0 2s 5d

------------

Page 3 Sub Total £151 0s 0d

The Rev William Hickey £1 0s 0d

James Kenak ? £0 2s 5d

Mrs Neale £0 2s 5d

Widow Keily £0 2s 5d

Peter Green £0 2s 0d

William Kelly £0 2s 0d

Thomas Foley £0 2s 0d

Thomas Hickey £0 2s 0d

Thomas Forster Jones £0 2s 0d

William Jackson £0 1s 0d

Thomas Salter £0 1s 0d

Patrick Terry £0 1s 0d

James Leahy £0 1s 0d

Michael Tobin £0 5s 0d

------------

Total £153 7s 5d

========

Signed H D Sheppard Treasurer

14th Jan 1847

We certify that all the subscriptions set forth in this list have been collected and paid to the Treasurer of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee and that there is not included in it, any sum contributed from funds applicable to Charitable purposes.

Signed Georg Roch Chairman of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee and

William Wakeham Hon. Secy. Curate of Kinsalebeg Youghal.”

Additional Subscriptions to the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee (1847):

Rev H H Beamish (Collected in London) £30 0s 0d

Mrs Neale £4 0s 0d

G.G. Downes Esq £1 1s 0d

Ensign James Nicol 13th Light Infantry £4 0s 0d

Sir John Kennedy 2nd donation £2 10s 0d

The Society of Friends £20 0s 0d

The Belfast Relief Association £10 0s 0d

Mr James Goodwin £2 10s 0d

Peter Fisher Esq 2nd donation £5 0s 0d

The Rev F Chalmers (Leamington) £2 0s 0d

Mrs Chalmers £5 0s 0d

Mrs Stephenson (Durham) £5 0s 0d

Mrs Hewett ? Counnington ? £2 0s 0d

Mrs Chevalier (Durham) £5 0s 0d

Rev R Ramsdem` £2 15s 5d

Rev T French (Oxford) £1 0s 0d

Rev T Ballard £1 0s 0d

Rev T Chevalier £5 0s 0d

Miss ? Marsh (Leamington) £5 0s 0d

-------------

Sub Total £113 10s 5d

========

We certify that the subscriptions set forth in the above list have been collected and paid.”

Date 12th January 1847: This letter was from Rev William Wakeham, secretary of Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee, to Mr Stanley, secretary of Commissary Relief Office at Dublin Castle. Rev William Wakeham was applying for additional aid to partially match the funds that had been locally raised in Kinsalebeg. He makes a significant statement to the effect that to date Kinsalebeg had largely been spared the widespread deaths of the famine as a result of the effective relief efforts in the parish:

“Kinsalebeg Youghal

12th Jan 1847

Sir,

I beg leave to acknowledge the Commissary General Sir Randolph Rouths communication of the 8th inst. [made this year?], to the effect that Sir R Routh had recommended his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant to grant a donation of one hundred and fifty three pounds for the Relief District of Kinsalebeg on condition that the [whole] Relief fund should be applied agreeable to the instructions and Treasury minutes referred to therein.

I beg leave to observe that as Secretary of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee in making application for a grant in aid of the funds collected in the District I stated for the information of Sir R Routh, the mode in which relief had been to this so afforded to the destitute poor from the funds collected, by the Committee.

It is under the Providence of God, that to such exertions and the measure of relief thus afforded this District has been to the present time preserved from the calamity of deaths arising from starvation. The Committee feel the strongest conviction of the necessity existing for the continuance of such a moderate system of relief in the extreme price of provisions at the present season, and that it is by being enabled to administer such relief the calamities of the suffering poor and by humanely affording small supplies of food in weekly distribution at a reduced rate to the really destitute, avert with the Blessing of the Almighty, the dreadful catastrophe of famine and its consequences in this district. Trusting the circumstances as stated in the case of Kinsalebeg Relief Districts shall meet the [approval ?] of Sir Randolph Routh and will not be denied authorise [thus] in conformity with a humane consideration and view of the instructions and Treasury minutes of which I have seen enclosed copies.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your Most Obedient Servant

Wm Wakeham Clk

Secy. Kinsalebeg Relief Committee

To Mr. Stanley Esq. Secy Commissary Relief Office Dublin Castle”

Date 21st January 1847: This is another letter from Rev. William Wakeham, secretary of the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee, to the Famine Relief Commission at Dublin Castle.

Kinsalebeg Youghal

21st January 1847

Sir,

I beg leave to acknowledge Sir Randolph J. Rouths communication of the 16th inst. [made this year?].

[To avoid?] any claim of unnecessarily trespassing on the attention of Sir R Routh or with [other objections?] than that of receiving his sanction for the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee continuing the mode of relief which in our experience has been found most effective and suited to the circumstances of the poor in this district. I beg leave to submit a reply that the Committee has been for months affording assistance to the cases requiring relief in the many communications for Sir R. Rouths information in my prior letters and subsequently referred to by a weekly distribution of meal in quantities ranging from ½ to 2½ stone according to the circumstance of the family and at a reduction from cost price of from 1/8th to 1/5th to meet the pressure of the poor according to the state of the Market. This mode of relief has been found simple in its application, and not liable to abuse under careful superintendence of the Committee. Its arrangement and [system?] are well understood by the Committee as are the benefits [of the?] relief. In the great number of cases requiring relief state of partial distribution has arisen, from such causes – a loan rate of [wages?] 10% men and 6% women per diem – the employments on public works on which the poor are independent is inadequate to support families being given in a population of [our mean] of four in a family and the exorbitant price for provisions at the present time. The Committee believe under such a state, that giving relief by a moderate reduction in the prices of small supplies of food is far more advantageous to their relief, and requires a less expenditure of the funds than the adoption of a more general gratuitous relief which otherwise might be necessary.

The Committee are offering gratuitous relief in cases of extreme distress [ ??] causes referred to in Sir R Rouths communications by distributing soup. I beg to add the resolutions passed in the Committee after I had submitted to Sir R Rouths communication.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your Obedient Servant

Wm. Wakeham Clk Secy

The above letter had what appears to be the draft of a response from the Famine Relief Commission at Dublin Castle. The draft response was written at the bottom of the letter and it indicates agreement with the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee as to the strategy that they have devised for famine relief in Kinsalebeg, particularly as it appears to be working very well. Draft response as follows:

“Copy of Contributions ?.

[Resolve?], that the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee in the application of the funds collected in the District for relief of the poor having acted on the system communicated by the Secretary to Sir R. Routh, considers it has found most effective and suitable for relieving the distress of poor and has prevented much aggravated suffering and calamity in the District.

[Resolve?], that the Committee respects fully [views?] to express their conviction of the inexpediency of changing from this mode of relief which experience has found so effective, hitherto, in which the prices of provisions remain as at present extremely high and the rate of wages for employment is inadequate for support of the poor.”

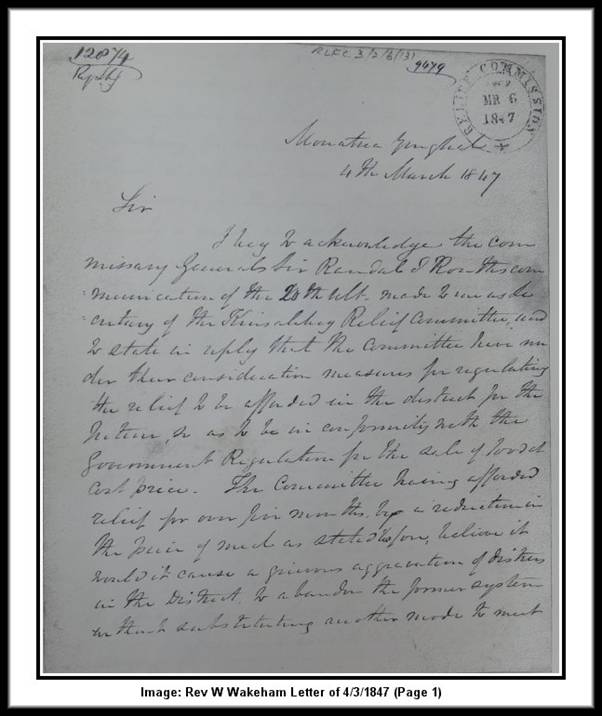

Date 4th March 1847: Another letter from Rev. William Wakeham, secretary of the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee, to Mr Stanley, secretary Commissary Relief Office at Dublin Castle. In the letter Rev Wakeham states that the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee were considering measures to ensure they were in compliance with instruction to relief committees from Dublin Castle Relief Commissary but they were unwilling to discontinue their existing successful relief methods without having a suitable alternative strategy in place. The officials in Dublin Castle appeared to be concerned that the actions of the relief committees would not affect the corn market. Kinsalebeg Relief Committee for example had established an effective and successful famine relief system whereby they were supplying small quantities of corn & meal on a weekly basis to around 250 needy families either at cost price or up to 20% below cost. In addition they were supplying free soup and meal to destitute Kinsalebeg parishioners who had no capacity to pay and were unable to work in lieu. The Relief Commission in Dublin Castle were concerned that a free-for-all system of relief would not be sustainable and would have a negative effect on the corn market. In the end it would appear that Kinsalebeg Relief Committee continued with their own successful system of famine relief whilst writing polite letters to Dublin Castle to keep them off their backs. Rev Wakeham threw in a small hand grenade at the end of the letter when he mentioned that Kinsalebeg had a mill available and were now in a position to supply bread at cost price to parishioners. This probably instilled a new fear in Dublin Castle that Kinsalebeg were now going to possibly disrupt the bread market as well as affecting the corn market. It would appear that the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee were working in co-operation with Abraham Fisher and his family at Pilltown Mills to provide as effective a system of famine relief as was available anywhere in the country. The following is a transcript of the letter from Rev William Wakeham to the Relief Committee dated 4th March 1846 and we also include a copy of the original letter.

Monatrea Youghal

4th March 1847

Sir,

I beg to acknowledge the Commissary General Sir Randolph Rouths communication of the 20th ult. Made to me as secretary of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee and I state in reply that the Committee have under their consideration measures for regulating the relief to be afforded in the district for the future, so as to be in conformity with the Government Regulations for the sale of food at cost price. The Committee having afforded relief for over [?] months, by a reduction in price of such as [ ?}, believe it would cause a grievous aggravation of distress in the District to abandon the former system without substituting another mode to meet the necessities of the poor without adopting a gratuitous issue of food extensively.

It is proposed by the Committee to establish a bakery for supplying bread at Irish cost which it is believed would effect a considerable saving for the poor. The Committee have already a mill and other conveniences in place for the purpose, which would enable them to supply cheap and wholesome bread for the relief of the District at cost price with considerable advantage, and also provide for gratuitous distribution when necessary the supplies that may be required.

Desiring to submit the above measures for Sir R. J. Rouths approval.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your Obedient Servant

Wm. Wakeham Clk

To Mr. Stanley Esq. Secy, Commissary Relief Office”

The above two images are the two pages of Rev William Wakeham’s letter of 4th March 1847 to Mr Stanley & Sir Randolph Routh of the Famine Relief Commission in Dublin Castle. The text of the letter is included before the images as the original letter has deteriorated over the centuries.

Date March 1847: The Rev. William Wakeham, secretary of Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committtee, writes to Mr Stanley, secretary Famine Commissary Office, Dublin Castle. Rev Wakeham confirms that the list of subscriptions to Kinsalebeg Relief Committee has been forwarded to Sir Randolph Routh. He outlines that one of the soup boilers in Kinsalebeg has developed a fault and requests that a replacement be forwarded by carrier to Youghal from the supply of boilers recently sent to Cork.

Monatrea Youghal

? March 1847

Sir,

I beg to acknowledge the [point?] circular of Sir Rd. Routh addressed to Relief Committees [this year?] and according to the suggestion lost no time in forwarding a list of subscriptions for Sir R.J. Rouths recommendation to his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant of a grant in aid.

I beg leave to state that since the answers to the issues of the Relief Commissioners were forwarded, an accident has occurred to one of the boilers [in case?] which could be repaired only in a way for temporary use until another boiler should be supplied, and that it is to be apprehended from this increased work is now necessary to supply the destitute poor, that it may not hold out for any time as there appears [presently?] a leakage from it. As it appears from the circular that boilers have been sent to Cork for the use of Committees I would beg to suggest an order directing one for the use of this district which can be forwarded to Youghal in the most direct way as there exists constant appointments by carriers between the towns. I am daily fearing lest this [source] of relief for the District shall have to be suspended. On the part of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee I beg to offer their grateful acknowledgements in closing this correspondence with Sir R.J. Routh for the courtesy and attention received in the communications from the Commissary General.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your Obedient Servant

Wm. Wakeham Secy.

Kinsalebeg Committee

To Mr Stanley Esq. Commissary Office

Date 17th April 1847: The Rev. William Wakeham, treasurer of Kinsalebeg Relief Committee, writes another letter to Mr. Stanley, secretary of Relief Commission Office at Dublin Castle. In it he confirms that a donation of £20 from the Society of Friends [Quakers] was paid in cash as were all other subscriptions to the relief fund. The letter was obviously a reply to a query from Dublin Castle as to the makeup of a £20 donation from the Society of Friends to the Kinsalebeg Famine Relief Committee but it is not clear why Dublin Castle were enquiring about this specific donation over any other – was it some concern over a Quaker involvement in the famine relief program or was it in some way concerned with the known financial problems of the best know local Quaker family namely the Fishers of Pilltown. Peter Fisher of Pilltown had also made a £10 donation and followed this up with a second subscription of £5 as can be seen from the subscription list. The Fishers of Pilltown, as we have noted elsewhere, made a massive contribution to not only the famine relief program in Kinsalebeg but to a range of other charitable causes even at a time when they had their own financial problems. Abraham Fisher was involved in the Cork Quaker Auxiliary Committee which was another famine relief committee operating in Kinsalebeg at the time.

It is interesting to note that Rev William Wakeham signed himself as treasurer rather than secretary of the Kinsalebeg Relief Committee which he had been up to that point. It is possible that he was both treasurer and secretary at the same time and signed as treasurer in view of the financial nature of the correspondence. This letter was the last known correspondence from Rev. Wm Wakeham to the Relief Commission in Dublin Castle. He died in Kinsalebeg two months later and must have been a grievous loss to the famine relief effort in Kinsalebeg to which he had made an extraordinary and selfless contribution in the years previously.

Monatrea Youghal

17th April 1847

Sir,

In reply to your letter of 15th inst. making an enquiry for Sir R. Rouths information as to a grant of £20 from the Society of Friends in aid of the District of Kinsalebeg Co. Waterford. I beg to state the contribution as all of those returned in the subscription list from this District, was made in money.

I have the Honour

To be Sir

Your Obedient Servant

Wm. Wakeham, curate of Kinsalebeg

Treasurer of Relief Committee for Kinsalebeg

To Mr Stanley Esq. Secy

![]()

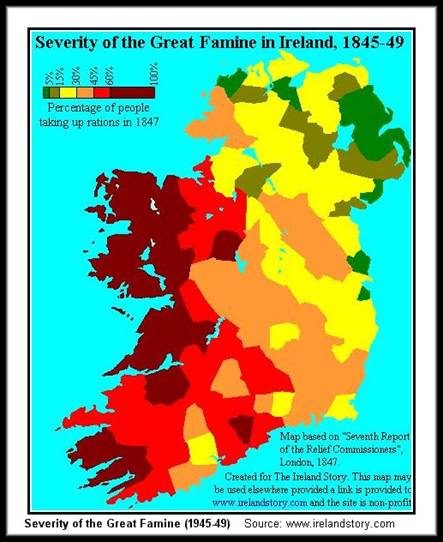

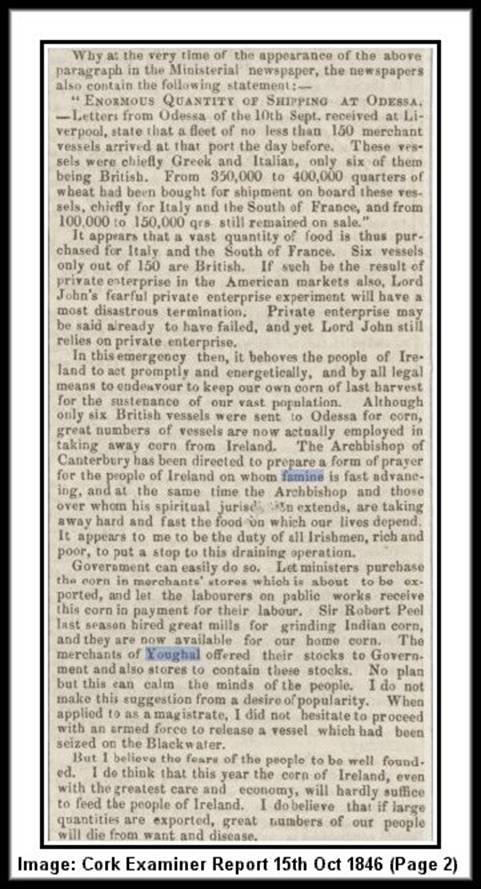

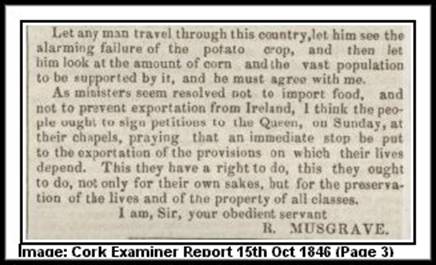

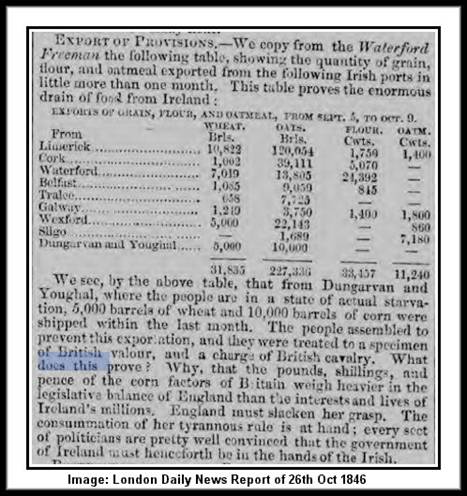

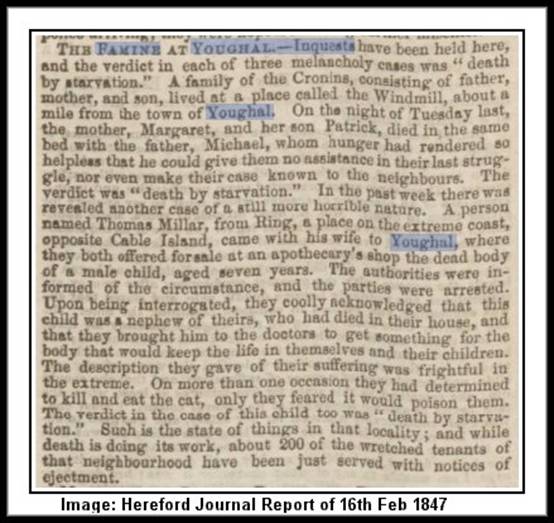

Newspaper Reports Concerning the Famine

Food Riots in Youghal area (September 1846):

Date 23rd September 1846: The following reports and letters appeared in the Examiner and recounts events surrounding the food riots in Youghal in September 1846:

Title: Food Riots in Youghal. Destruction of the Bakers’ Shops [From Our Reporter].

Article: “After the termination of the meeting held in this town on Monday last, our reporter was surprised to see a large concourse of persons, exclusively of the labouring classes, hurrying from one street to another, apparently in a most excited manner. On making inquiry, it was ascertained that this demonstration was made in order to prevent the merchants and manufacturers from exporting the corn or provisions of the town, for which purpose upwards of a dozen ships were lying in the harbour. After visiting several of the corn stores with the apparent intention of intimidating the proprietors, the mob proceeded down to the quay, where they speedily compelled some Carmen, who were loading the vessels with corn for exportation, to desist and return to the stores; on coming back, they met another carman who however, did not remain to receive the injunctions of the mob, but immediately turned the horse’s head, and commenced a speedy retreat amidst the cheers and jeers of the multitude. Not satisfied with their success in these instances, they turned towards another portion of the quay, where they succeeded in a similar manner. Up to four o’clock their proceedings were confined to preventing the exportation of provisions; and by the respectable portion of the inhabitants, it was anticipated that no actual violence would be the result; but unfortunately their expectations were frustrated. The mob, elated probably by the success of their first attempt, commenced at a later period of the day to demolish the flour and bread shops, which was only partially prevented by the interference of the Military. I understand, in consequence of the extent to which these outrages were carried, that Mr. Kelly, J.P., arrived in this City on yesterday, for the purpose of consulting with the General of the district, and obtaining a large reinforcement of military.”

“The following letters have been received from highly respectable and intelligent correspondents. They give a frightful detail of the extremities to which hunger and misery will drive even a “patient people,” and are entitled to the serious consideration of the government and the landlords.”

“From a Correspondent Youghal Monday Night: After the meeting, and, I presume, the departure of your reporter, the town presented an awful scene. Most of the bread shops were broken into by the multitude, and plundered. There were military of all sorts parading the streets, from the dense and bustling state of which one would imagine that the town was in actual state of siege. At this late hour (ten o’clock) soldiers are parading and drums beating, but no further accident has occurred. God help the country !”

“From another correspondent Youghal Tuesday, 12 o’clock: It would be impossible to convey any idea of the alarming state of this town since yesterday’s meeting. The people were dissatisfied at the proceedings there, as not a single resolution except the last, which was proposed by Mr. Barry, was at all capable of being carried into effect for a month or six weeks, while the people are at this moment driven to frenzy and despair for food. Like men maddened with hunger, they ran through the streets – they rushed into the bread-shops, and flung the loaves amongst the famish[ed] crowd. The military were called out – cavalry, infantry and police – but half the shops were plundered before they arrived. On this morning (Tuesday) an immense number of people from the adjoining parishes came in, with hunger depicted on their faces. The military are now marching through the town, and the unfortunate people are at this moment, while I write, in hundreds tearing the bread out of the shops. The town is in the most dreadful state of excitement – the shops closed – business suspended – groups assembling in a few places, not knowing what the result will be; and unless the Relief Committee act promptly in getting a supply of food, and giving employment until the Public Works are in operation, God only knows what a starving people will do. Mr John, whose exertions on behalf of the people are unceasing, as I have been told, convened a meeting of the Relief Committee, and it is expected that they will expend the £400 which they have at present on hands, in giving immediate employment. If not, the result will be, I fear, appalling. There are gangs stationed at either end of the town to prevent corn from coming to market – the portcullis of the bridge is raised – and the town has more the appearance of a siege than of business. I trust the Relief Committee will now see the necessity of acting promptly and decisively, and expend this money – for hunger will admit of no delay. A famishing people acknowledge no laws, even in those days of enlightenment.”

“From another correspondent Youghal, Sept. 22: Anything to equal the state of excitement here I never knew – the people are frantic – they have already (at 12 o’clock) plundered almost every bread shop in the town.”

“From another correspondent Youghal, Sept. 21, 1846: This moment my shop was broken into and all the bread therein taken away – there were several other shops treated in a like manner. The mob were chiefly from that part of the country called the Barony. Yours in haste, John O’Brien. P.S. While I was trying to keep them out they treated me very badly and tore all my clothes.”

“ The following we received this morning: Youghal, Tuesday Night:- Since I wrote to-day, placards have been issued by the Relief Committee stating that they will now employ the people, and sell food at a reduced price. Time for them. When they are obliged to do it.”

Attack on Lord Stuart de Decies (September 1846):

Date 25th September 1846: The report outlined below in the Examiner, dated 25th September 1846, outlines an attack on the Eton educated Lord Stuart in Clashmore in September 1846. Lord Stuart de Decies or Henry-Villiers Stuart of Dromana had shocked both the British Parliament and the Irish ruling classes when he was elected MP to the British Parliament in 1826 after fighting a campaign in support of Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation. He lost the seat in the 1830 general election and was appointed Lieutenant of Waterford in 1831 and was still Lord Lieutenant of Waterford at the time of the famine – hence the anger of the people in the Clashmore area who felt that he should be doing more to alleviate the distress resulting from the famine. The position of lieutenant of a county was based on the English model and was introduced into Ireland as a replacement for the old Irish position of governor of a county. Henry-Villiers Stuart was created a baron in 1839 and given the title of Lord Stuart de Decies. The title became extinct on his death in 1874 as there was some uncertainty about the legitimacy of his marriage as a result of which his son Henry-Villiers-Stuart did not succeed to the title. The Examiner report on the Clashmore incident was as follows and as noted elsewhere it is important to bear in mind that most newspaper articles in earlier centuries were coming from a particular viewpoint and genuine unbiased reports were not usually available. The famine reports in particular do not always reflect the absolute desperation of a starving population.

Title: Disgraceful Attack on Lord Stuart De Decies

Article: [From a correspondent]. “On Wednesday last the adjourned Road Sessions was held at Clashmore, for the barony of Decies within Drum, in the county of Waterford; and the Magistrates, having finished the business about five o’clock, left the Court-house to proceed to their respective residences, when a large mob of about at least 3000 persons commenced throwing stones at Lord Stuart De Decies, the Lieutenant of the county. The Dragons charged them, under volley of stones, and must have wounded several of the rioters. One man had his ear and the side of his face cut off. Lord Huntingdon, Sir Richard Musgrave, Thomas J. Fitzgerald, Simon Bagge, and Richard Power Ronayne, Esqs,. Magistrates, rushed among the mob, and did all they could to stop the throwing of stones, and but for their interference, the Dragons would have fired, as they could not stand the stone throwing, particularly from the Church-yard. Nothing could equal the fury of the mob against his Lordship, and Sir Henry W. Barron, who fortunately was not at the sessions. Several of the Dragoons were severely hurt. We are happy to say his Lordship escaped unhurt – but for the Dragoons he would certainly have been murdered. It is most extraordinary why his Lordship should have been selected for such a murderous attack, for he is a kind and very indulgent landlord, and sets his ground for the value of the occupiers, and has 60 men employed at Ballyheeney (close to the scene of attack), draining, at which they earn one shilling and six-pence a day, besides employing about 300 men on other parts of his estate. He was also most anxious, with the other magistrates, to pass all works, to give employment, and intended to drain every acre of wet land on his estate. There is but one feeling prevailing among all well disposed persons, that this was a most disgraceful and undeserved attack on a good resident landlord and magistrate, who is daily doing acts of kindness for the poor.”

Disturbances in Pilltown, Clashmore and Youghal (September 1846):

Date 29th September 1846: The following report in the Times of London in September 1846 describes the tense situation and disturbances in Youghal, Clashmore and Pilltown at that time. The report on Clashmore describes the attack on Lord Stuart De Decies (Henry Villiers Stuart of Dromana). We have covered this in an Examiner report elsewhere but this article throws up a few different points. It mentions that one of the causes of the riots in Clashmore was the grievances a number of people had with Lord Stuart. One of the grievances was his “small subscription of 5 pound only to the relief fund”. Lord Stuart wrote a letter to the Cork Constitution paper later defending his position and we have included this article elsewhere. The people of Clashmore had a point if the £5 donation was true as Lord Stuart was one of the bigger landlords in the area and he was definitely not stretching his resources by throwing in a fiver to the Clashmore Famine Relief Fund. However the official List of Subscribers to the Clashmore and Kinsalebeg Relief Fund indicates that Lord Stuart De Decies had in fact made a donation of £25 to the fund so the rumour about his £5 contribution seemed to be incorrect unless the subscription list was drawn up at a later stage when he had decided to increase his subscription. The Clashmore fund seemed to cover both Clashmore and Kinsalebeg, according to the subscription list, even though Kinsalebeg had their own separate fund as we have listed elsewhere. We will have to assume that the relative proportion of the combined Clashmore & Kinsalebeg relief fund was passed on to Kinsalebeg in due course. Other large contributors to the combined Clashmore and Kinsalebeg relief fund were Mrs Percy Scott Smyth with £30, the Duke of Devonshire with £20, the Earl of Huntingdon and George P Mansfield with £10 each. The contributors to the separate Kinsalebeg Relief fund included:- Mrs Scott Smyth of Ballynatray & Monatray who contributed £30, the Quakers (Society of Friends) contributed £20, Peter Fisher of Pilltown Mills contributed £15 in two subscriptions, Declan Tracy of Pilltown contributed £10 as did the Duke of Devonshire, George Roch contributed £5 5s, Rev H H Beamish Vicar of Kinsalebeg contributed £5 and also raised an additional £30 from fund raising in London. Even the impoverished curate of Kinsalebeg, Rev William Wakeham, contributed £3 whilst complete strangers to Kinsalebeg like Rev T Chevalier BD & Professor of Mathematics at Durham University and his wife contributed £10 between the two of them.

Lord Stuart’s popularity was not helped when he stated, from his position of chairman of the sessions in Clashmore, that 10 pence a day was ample wages for anyone. It was apparent from various reports during the famine period that people in general were not looking for food for nothing even though there was obviously a number who were unable to work due to infirmity or their poor health due to lack of food. Many of the demonstrations and disturbances were concerned with people looking for work which in turn would enable them to buy food – they were not looking for food for nothing despite the desperate hunger. Another key aspect of the demonstrations and the general anger of people at the time was the corn situation. People were naturally concerned that corn continued to be exported while the famine raged around them. They were also concerned that the price of corn was being increased to a level which they could no longer afford. Lord Stuart’s suggestion that 10 pence a day was sufficient wages was not helpful when the price of corn and other foodstuffs had increased substantially. Whereas baker shops were looted during some demonstrations the focus was generally on the issues around the famine such as lack of work, wages, food prices etc. The following is the full Times article:

“Title: Ireland (from our correspondent, Dublin September 25 [1846]

Article: Youghal, Thursday:-

“The town and its immediate vicinity have been comparatively quiet this day; 500 men are at work, many of them at labour quite useless; employment has, however, quieted the population for the present, but many of those at work have left their regular service with the farmers, and a good deal of harm will arise from a continuance of this practice. The funds of the relief committee will be exhausted in a few days; they, this day, sent off for a further supply of £350 worth of Indian meal. Mr. Knaresborough R.M. is still remaining in town.

The scene at the adjourned presentment sessions, for the barony of Decies within Drum, in the county of Waterford, held yesterday in Clashmore, about three miles from Youghal, was frightful; thousands were congregated there, most of them Lord Stuart’s tenants in Slieve Greine mountains. These wretched people have held small patches of the mountain at a mere nominal rent, are quite paupers, and have lost their entire supply of food; at best they are not of the most orderly or quietly disposed. Lord Stuart De Decies was in the chair. The Earl of Huntingdon, Sir R. Musgrave, Mr Richard Ronayne, of Laughtane, justice of the peace, Mr. Francis Kennedy, of Ballinamultina, justice of the peace, Rev. W. Mackessy, Rev. Henry Leech, and several other influential gentlemen, were present at the petty sessions house. The people were so dense it was almost impossible to get close to the court; many were clamorous and violent for food, which was supplied to not a few from the shops and houses of the village, but in such a small place, to so great an assemblage, it was no more than a drop in the ocean. The business of the sessions was despatched with a good deal of confusion; nearly every work asked for was granted, to the amount of thousands of pounds. As the proceedings were drawing to a close, it was apparent a bad spirit was abroad amongst the people. Several expressions of a violent nature were made respecting Lord Stuart’s small subscription of £5 only to the relief fund, and also as to his having stated from the chair that 10d. a day was ample wages, and that the work could not be commenced in less than 10 days.

The magistrates were going away as quickly as they could, after endeavouring to quiet and appease them as much as possible, for which purpose Sir Richard Musgrave appeared to be the most effective instrument, and a party of the 8th Hussars were stationed some short way off prepared to form an escort. When Lord Stuart, who was one of the last of the authorities to leave the session house, appeared amongst the crowd, their excitement grew to an intense pitch; menaces, threats, and opprobrious epithets were showered on him, which were succeeded by attempts at violence. With some difficulty he got into his carriage, when immediately his servant put the horse in a gallop, and flogged them most violently to keep them at the fullest speed. The mob followed in numbers, many of them by a short route, to stop his departure, and proceeded to extremities, which Sir Richard Musgrave perceiving, a party of the Hussars was despatched for his escort and protection; with difficulty they were enabled to keep them back, and his Lordship fled to Dromana at full speed. On the Hussars’ return, the mob gathered in the churchyard, which is much higher than the road, armed with stones, and with most violent yells and execrations against the military they immediately commenced an attack on them. A ringleader, named Power, from the parish of Grange, was very severely sabered, but was carried off by the populace, when their assaults were redoubled; several of the horsemen were severely hurt, and the force being small, they had to retreat for their lives to Lord Huntingdon’s farm yard, which was immediately barricaded. The crowd committed no violence on the inhabitants of Clashmore, and left the place by degrees as night approached.”

Disturbances at Pilltown Mills (September 1846):

Date 29th September 1846: The following is a continuation of the above report on the riots in Clashmore and outlines a seemingly separate disturbance in Pilltown on the same day when a mob marched on Fisher’s Mill and Ferrypoint. This protest was mainly about the shipping of corn from the Waterford side of the Blackwater River to the markets and merchants in Youghal primarily for export. Some of this corn would probably have been coming from Fishers Mill in Pilltown.

Article: “Thursday, a mob of thousands marched down to Mr Fisher’s mill at Pilltown, just opposite Youghal, on the county of Waterford side, vowing vengeance if Indian meal was not sold at 1s. per stone from the mill, and corn ground for 1d. per stone; they then proceeded, armed with sticks, stones, spades, hammers (such as are used in repairing roads), and other weapons, to the Ferrypoint, just opposite the centre of the town, and considerable apprehension was excited that they meant to attack it. The magistrates had the military in readiness immediately to repel them, but they contented themselves with threats of vengeance against the ferrymen and boatmen should they carry corn or provisions over to the Youghal merchants. The house of a farmer named Wynne was plundered; several other farmers were sworn not to take their corn over to Youghal, and again they marched down to the Ferrypoint to show themselves.”

Richard Harrison recounts a slightly different version of the above event in his book on Irish Quakers8. His version is as follows:

“One Fifth-day he [Peter Moor Fisher] was proceeding to Meeting [Quaker Monthly Meeting] with his family, when an agitated man rushed up to him to ask if he knew that a dangerous mob was marching towards the mill, and would kill him and nail his ears to the door, and asked, ‘Have you left the police in charge ?’ Peter replied ‘Yes’ to the first question and ‘No’ to the second question. ‘Do’st thou not know that it is our morning Meeting ? The mill is shut up as usual and all is left in the care of my Heavenly Father.’ The mob did indeed rush up to the mill but only to shout, ‘Three cheers for Mr. Fisher’.”

There is no doubt that Peter Moor Fisher was popular locally in Kinsalebeg and it is unlikely that he would have come to any harm from the assembled crowd. In any case he was not going to be diverted from the regular Quaker Monthly Meeting in Youghal and was quite happy to leave the security of Pilltown Mills in the hands of God!.

Youghal Reaction to Protest on Ferrypoint:

Date: 3rd October 1846: The Reading Mercury newspaper carried the above story about the thousands who protested in Pilltown and Ferrypoint but continued with the following item on how the authorities in Youghal responded to the threat of an attack from the protestors on Ferrypoint. The protestors eventually dispersed as they were not equipped to match the fire power displayed by the over reacting forces from the Youghal side of the harbour. The Reading Mercury article continued as follows:

“An express having gone off to the Admiral at Cove from the magistrates [of Youghal], informing him of the navigation of the river being impeded, and requiring the assistance of a steam-ship; the Myrmidon was immediately despatched, and having a fair wind, arrived off the harbour at about half tide (three o’clock p.m.). The commander got out all his boats, filled with artillery and marines, and pulled into the harbour, the launch, carrying a 9-pounder in her bow, coming in last; the steamer coming to an anchor about half-past four. This seasonable arrival seemed to deter the country boys, and they again returned to their houses”.

Famine Disturbances in Dungarvan (October 1846):

Date Friday 2nd October 1846: A report appeared in the Examiner concerning disturbances in Dungarvan during the famine. The disturbances are also described in the Waterford Freeman newspaper on the 5th November 1846.

Title: The Dungarvan Disturbances

Article: “[From the Correspondent of the Waterford Chronicle] Dungarvan, Monday Night:-

About 12 o’clock, the square and streets began partially to fill with people, and at half-past one, a body of labourers from Old Parish, Ardmore and Clashmore, to a number of something near seven hundred, entered the square and marched in procession down the Quay towards Mr. Flood’s store, when they cautioned him against shipping any corn. From thence they proceeded towards the square, but on their way to the Main-street they were invited by a baker, named Morgan, to partake of what bread he had in his shop. This they refused, and said they only wanted employment and a proper rate of wages. They then scattered through the streets and square, which were almost inaccessible, so crowded were they. In the meantime a few mounted police were passing to-and-fro amongst the people. Police from several stations were placed at the Court-house doors.