History of Kinsalebeg

Events in History of Kinsalebeg

Storming of Pilltown Castle on 18th August 1646

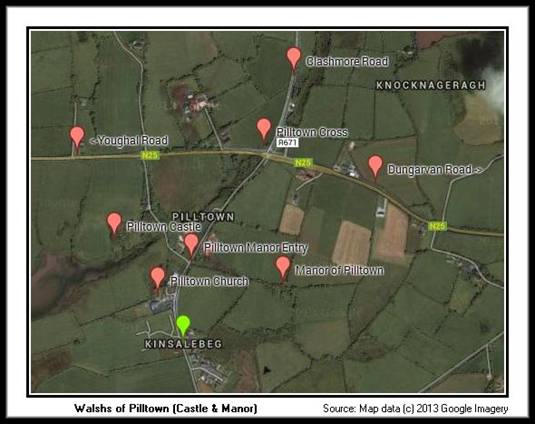

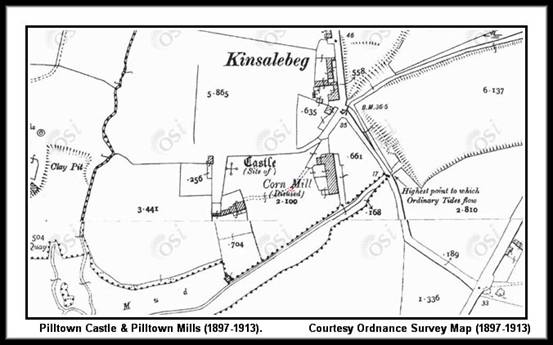

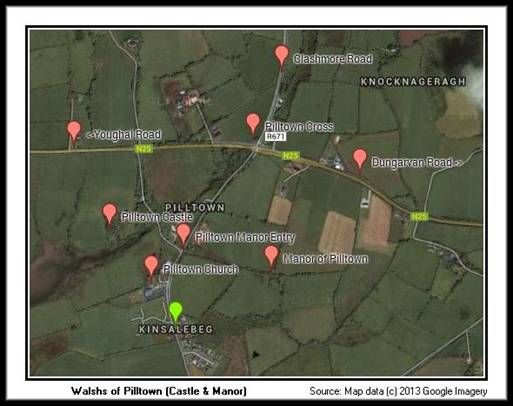

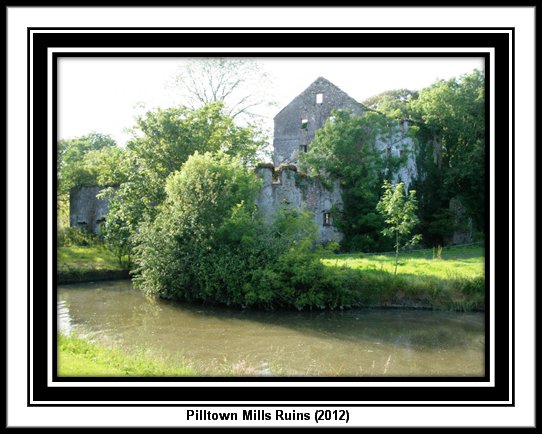

Pilltown Castle was located adjacent to the present day ruins of Pilltown Mills which is located close to Pilltown Church in the parish of Kinsalebeg Co. Waterford. The Blackwater River has a high tide inlet here which made it suitable for the industrial and indeed military activities which took place in that area over the centuries as it provided shipping access to the Blackwater River and Youghal Bay. Pilltown Castle was originally part of the large Munster estates of the Earls of Desmond or Geraldines which were confiscated after the failed Desmond rebellion of 1579. The castle and surrounding land came into possession of the Walshs of Pilltown when the Desmond estates were broken up after the rebellion.

Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior and his sons took leading roles in Irish rebel activities before and during the 1641 rebellion. The family were involved in numerous rebel actions mainly in the West Waterford area and Nicholas Walsh Jnr was the alleged author of the “forged commission” from Charles I which heralded the breakout of the rebellion in 1641. Pilltown Castle was in a key strategic location between West Waterford and Youghal and was the subject of numerous attacks during the 1641 rebellion. The occupancy of the castle switched between the Walsh led rebel side and the Lord Broghill led parliamentary side at different stages during the early part of the rebellion. Sir Nicholas Walsh Jnr was killed during the rebel capture of Dungarvan Castle in 1643 and was succeeded by his son Thomas Walsh.

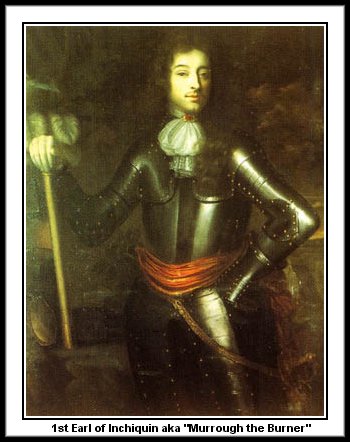

Pilltown Castle was in Irish Confederate rebel hands in 1646 and it again became the focus of attention for the Cromwell influenced Parliamentary forces. The castle came under siege from the Parliamentary forces on the 18th August 1646 and was defended by the Irish Confederates. The Parliamentary attack on Pilltown was led by the infamous Earl of Inchiquin together with his army of almost three thousand foot and horse mounted soldiers. The Earl of Inchiquin was the Irishman Murrough O’Brien who earned the nickname of “Murchadh na dTóiteán” or “Murrough the Burner” as a result of his “scorched earth” policy on the lands, houses and animals of anyone on the Confederate side of the rebellion.

Major General William Jephson was the second in command to the Earl of Inchiquin aka “Murrough the Burner” when the attack on Pilltown Castle took place in 1646. His description of the attack starts off with a description of the castle itself and it is one of the few records giving a picture of the layout of Pilltown Castle at the time. He describes it as “a very strong place”. The outer wall or earthworks was twenty foot high from the base of the surrounding moat to the top of the wall. Inside the outer earthworks there was a stone courtyard with a twelve foot wall and inside this was another courtyard also with a twelve foot wall. The castle entrance itself was inside this last wall. The Parliamentary forces eventually broke through the surrounding defensive structures with “the loss of some men and wounding of about twenty”. However having reached the inner castle walls the attacking army were initially unable to gain entry to the castle itself. They were subject to a barrage of stones from the top of the battlements which resulted in many injuries. The attacking forces eventually broke into the lower level of the castle but were unable to get up to the higher levels of the castle as Jephson outlines: “the rogues still defended it, and broke down the stone stairs to prevent our men from getting up to them.”

The Pilltown Confederate garrison stubbornly refused to surrender despite being overwhelmingly outnumbered by Inchiquin’s forces. Their refusal to surrender would have meant that they could expect no mercy if the castle was captured as this was the military convention at the time. The attacking army eventually decided that it was going to be virtually impossible to capture Pilltown Castle and they decided instead to destroy it. This would not have been a normal course of action at the time as castles were seen as valuable defences which would have been subsequently manned by the capturing forces. The attacking army were also enraged by the stubborn resistance and bravery of the Pilltown defenders. The attacking army put down gunpowder in the base of the castle and blew up the castle including all the occupants. The following is Jephson’s chilling account of the last stages of the attack on Pilltown Castle:

“We therefore, finding that without much mischief it was impossible to get them down, were forced to lay powder below, and blow them and the castle up together, which we did last night. My Lord President at his first summons thereof promised them fair quarter if they would surrender it before he discharged three pieces of ordnance against it, which they refusing, were by that means afterwards (the soldiers being also incensed) deprived of all their lives, it being taken by storm; only the women and children were turned out by the rebels of their own accord.”

There is no indication of the number of people killed in the massacre at Pilltown Castle on the 19th August 1646. According to Jephson everyone was killed except for some women and children who were sent out of the castle by the Confederates. Sir Percy Smyth of Youghal in a letter to Sir Philip Perceval on the 7th September 1646 stated that only seven people were spared in the massacre. He wrote that: “in which time we took Piltowne by storm, put all to the sword except seven persons”. It is reasonable to assume that the deaths on the Confederate side in the attack of Pilltown Castle were in the hundreds if not greater. Additional details on Pilltown Castle and the Walshs can be located under the Walshs of Pilltown chapter in the History of Kinsalebeg at www.kinsalebeg.com

![]()

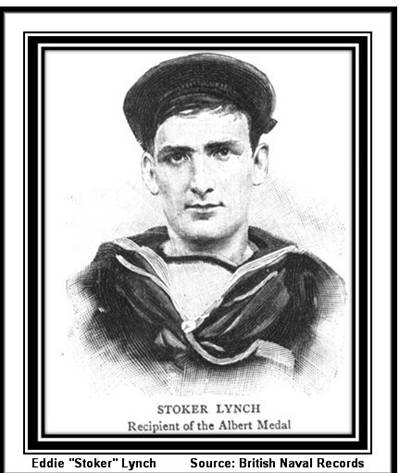

Naval Hero Stoker Lynch Awarded 1st Class Albert Medal

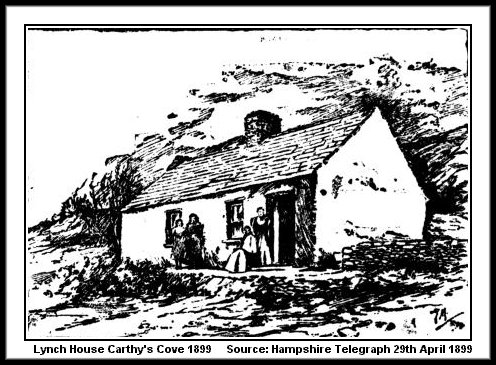

Edward “Stoker” Lynch of Carty’s Cove Monatray achieved legendary status in the Royal Navy for his bravery. His name is included in a list of the twenty five Most Notable Naval Personnel of the 19th century which was drawn up by the Royal Navy in recognition of notable achievements of naval personnel. The twenty five man list is predictably dominated by a mixture of Lords, Admirals, Vice Admirals, Lieutenant Generals, Commanders and Rear Admirals but embedded in the middle of the list we find the name of Stoker Lynch of Monatray. The bravery of Stoker Lynch became legendary in the British naval service and received widespread acclaim towards the end of the 19th century.

Edward “Stoker” Lynch was the son of Thomas Lynch and Mary Nason from Carty’s Cove, Monatray East, Kinsalebeg, Co Waterford and he was born in 1873. He joined the British Navy on 7th February 1896 for a twelve year period of service. In 1897 Edward “Stoker” Lynch or Stoker Lynch as he was better known was serving as a stoker on HMS Thrasher which was a B-Class torpedo boat destroyer of the British Royal Navy. On 27th September 1897 HMS Thrasher was one of three Royal Navy torpedo-boat destroyers which left the Royal Navy base at Devonport, Plymouth on a training mission. The HMS Thrasher was accompanied in the training flotilla by the HMS Sunfish and the HMS Lynx. The primary purpose of the training mission was to enable stokers and other engine-room ratings to become familiar with the watertube boilers which were being fitted to new naval ships at that time.

The three ships left Devonport in good weather but a dense fog descended on the flotilla as they were cruising off the Cornish coast on Wednesday 29th Sept 1897 and the ships became separated. HMS Thrasher had no forewarning of the danger ahead of it in the dense fog and hit the infamous Dodman Rocks between Fowey and Falmouth at a reputed speed of 12 knots causing serious damage to the ship. She was closely followed onto the rocks by the HMS Lynx which managed to escape serious damage and was subsequently able to make her return to Devonport under her own steam. The third ship in the flotilla, HMS Sunfish, managed to avoid the rocks and was unscathed. The notoriously dangerous Dodman Rocks were the scene of many shipping accidents down through the centuries and this part of the coast was a graveyard for many ships.

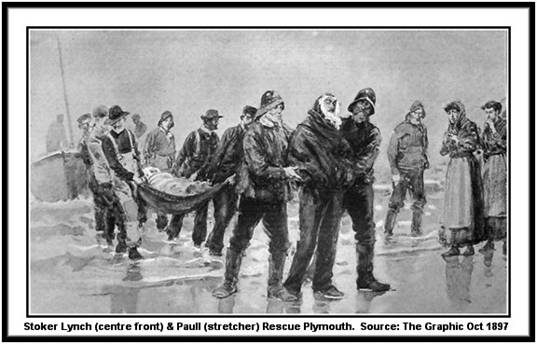

HMS Thrasher was extensively damaged in the accident and her back was broken on impact. Soon after the impact the main steampipe burst in a number of places causing a virtual inferno in the stokerhold where six stokers were on duty at the time including Stoker Lynch. The chief stoker, Frederick Lang from Plymouth, was exiting the stokehold when the steampipe burst and he escaped without injury. Three stokers, including another Irishman Michael Kennedy from Ballylongford Co Kerry, were killed instantly by the scalding highly pressurised steam escaping from the burst pipes. The badly injured Stoker Lynch managed to clamber out of the stokehold inferno and reached the safety of the deck. The starboard hatchway exit from the stokehold was impassable due to the physical damage received in the accident. Stoker Lynch was forced to make his exit from the stokehold through the port hatchway which was adjacent to a break in the steampipe with scalding steam emitting. When he reached the deck Stoker Lynch realised that his colleague Stoker James Paull, from Teignmouth in Devon, had not managed to escape and he could hear Paull’s cries from the stokehold. Stoker Lynch immediately went back down the treacherous port hatchway into the steaming inferno in an attempt to save his colleague. He would have been well aware that he was unlikely to survive a second time in the cauldron of the stokehold and his shipping colleagues made strenuous efforts to prevent him returning to the death trap. Stoker Lynch managed to grab hold of James Paull, a big man by all accounts, and then dragged him up the gangway ladder through the scalding steam jets and on to the safety of the upper deck. Stoker Lynch received the bulk of his serious injuries in the rescue of James Paull.

The two badly injured stokers, Stoker Lynch and James Paull, were subsequently brought ashore at Gorran Haven in Plymouth where they received further treatment for their injuries at the house of the coastguard of Gorran. Stoker Lynch managed to walk ashore at Gorran Haven despite his injuries and according to the rescuers he was more concerned about the serious condition of his colleague Paull than his own serious injuries. Stoker James Paull unfortunately died of his injuries shortly after his arrival in Gorran. The death of James Paull had a profound effect on Stoker Lynch who was devastated at the death of his colleague. Edward Stoker Lynch spent a considerable period in the Royal Naval Hospital at Plymouth getting treatment for the injuries he received in September 1897. On two or three occasions he was reported to be close to death but he rallied in a remarkable manner according to reports. He was discharged from the Royal Naval Hospital of Plymouth just before Christmas 1898 and was allowed home to Monatray, Co Waterford.

In November 1897 Queen Victoria announced that she had authorised the Lords of the Admiralty to grant Stoker Lynch, of the torpedo boat destroyer Thrasher, the Albert Medal 1st Class for “outstanding bravery displayed in rescuing a comrade”. The Albert Medal 1st Class was the highest honour available at that time for bravery in life saving on land or sea. Stoker Lynch was the first naval seaman or person of the “lower deck”, as it was described at the time, to receive the 1st Class Albert Medal.

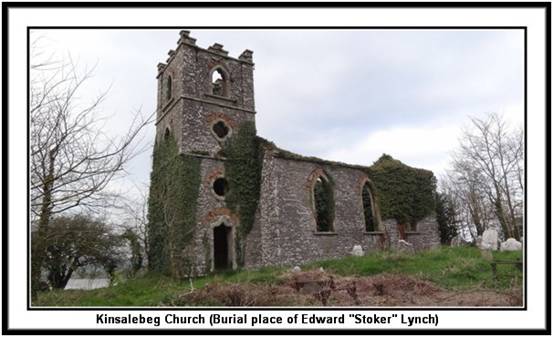

When Stoker Lynch finally returned to his home in Carty’s Cove, Monatray East around Christmas 1898 he was apparently suffering from consumption brough on by his injuries. He did not get much time to enjoy life in Monatray after his discharge from the Royal Naval Hospital as he died less than two months later on 1st February 1899 at the age of twenty six. He was buried with full naval honours at Kinsalebeg Church on 3rd February 1899. Thirty coastguards from the surrounding area formed a guard of honour and fired three volleys over his grave. The location of the grave of Edward “Stoker” Lynch in Kinsalebeg Church is no longer known but his memory should not be forgotten.

![]()

Sir Nicholas Walsh of Pilltown (1540-1615): Knight, Legislator & Politician

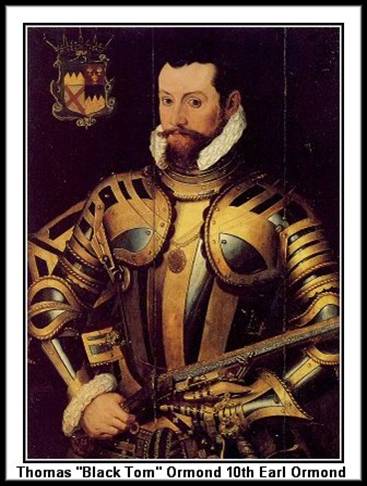

The Walshs of Pilltown were an influential West Waterford family from the 16th to the 18th century. Their history essentially starts with Nicholas Walsh who was born in Waterford City around 1540 and ends with the death of Colonel Robert Walsh who died in Bath in 1788. The intervening 250 years spanned some of the most turbulent periods in Irish history and the Walsh family were hugely involved in many aspects of this history. Nicholas Walsh was a son of James Walsh, a former Mayor of Waterford, and early in his life he was entrusted to the care of Thomas “Black Tom” Butler 10th Earl of Ormond. This association with the Earl of Ormond was to be a major influence in the life of Nicholas Walsh as the Ormond and Desmond dynasties dominated the political and military landscape in Munster in this period.

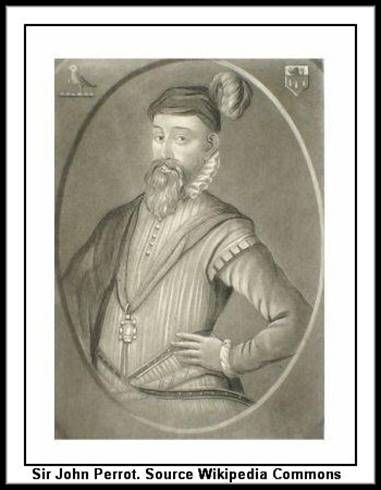

The young Nicholas Walsh also came under the influence of Nicholas White of Waterford, who later became a senior judge, and who influenced the decision of Nicholas Walsh to enter the legal profession. Nicholas Walsh obtained his legal education at King’s Inns in Dublin and Lincoln’s Inn London (1561) before returning to Waterford. He made rapid progress in the legal world and held the position of recorder of Waterford for many years. He was appointed second justice in Munster on the 14th December 1570 and in this capacity was a major support to Sir John Perrot who was President of Munster at that time. The following decades were dominated by various Desmond rebellions and Nicholas Walsh supported Perrot and the Earl of Ormond in their ongoing attempts to overthrow the Desmond dynasty. The Desmonds (FitzGeralds/Geraldines) were a permanent thorn in the side of the English authorities and their bitter rivalry with the Ormonds (Butlers) was the source of centuries of conflict. A major confrontation took place at the Battle of Affane in 1565 at which the Earl of Ormond inflicted a serious defeat on the Earl of Desmond who was then imprisoned.

In 1576 Nicholas Walsh was appointed to the position of Chief Justice of Munster by Queen Elizabeth I. Another Desmond rebellion broke out in 1579 but Nicholas Walsh in his role as Chief Justice of the province was not directly involved in this conflict. The conflict ended when the Earl of Desmond was hunted down and killed in Tralee Co Kerry in November 1583 by the local Moriarty clan. This effectively ended the Desmond influence in Munster and resulted in the breakup of the massive Desmond estates. The various legal and governmental positions occupied by Nicholas Walsh put him in an ideal position to keep track of the confiscation and distribution of land. He himself obtained substantial land holdings and property in Kinsalebeg as a result of the re-distribution of the Desmond estates. He also obtained land in other parts of Waterford including Stradbally and Kilrossanty but Kinsalebeg became the centre of Walsh operations in West Waterford. Nicholas Walsh came into possession of the Castle of Ballykeeroge in 1587 and he was also granted the Castle of Pilltown and Pilltown Manor around this period. These strongholds became the operational bases for future generations of the Walshs of Pilltown.

The Waterford land owned by the Walshs of Pilltown was primarily in the parishes of Kinsalebeg (3307 acres), Ardmore (280 acres), Clashmore (300 acres), Stradbally (770 acres) and Killrossanty (996 acres). The total West Waterford land holdings of the Walshs of Pilltown were therefore close to six thousand acres. They also owned substantial amounts of land in other areas such as Clonmore in Kilkenny and the overall Walsh landholdings after the post Desmond rebellion land distribution were in excess of ten thousand acres. The land owned by Nicholas Walsh in the Kinsalebeg area included the townlands of Monatray (900 acres), Newtown (168 acres), Pilltown (190 acres), Rath (253 acres), Glistenane (148 acres), Kilmeedy (300 acres), Drumgullane (300 acres), Knockbrack (140 acres), Lackendarra (66 acres), Kilmaloo (300 acres), D’Loughtane (214 acres), Kilgabriel (328 acres) and Garranaspic (100 acres). The other West Waterford land spanned the parishes of Ardmore, Clashmore, Stradbally and Kilrossanty as outlined above. The Kinsalebeg land was bounded on the western side by Youghal Bay and the River Blackwater and the main landowner in that area in this period was Sir Walter Raleigh.

John Perrot, the former Governor of Munster, was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1584 in succession to Arthur Grey. Perrot recognised that Nicholas Walsh was a very capable official who had established a formidable reputation in Munster and would be an important ally in the period ahead. In 1585 he appointed Nicholas Walsh as Second Justice of The Queen’s Bench which was one of the most senior judicial positions in Ireland. Nicholas Walsh was also elected as an MP for Waterford in the Perrot led Irish Parliament of 1585 and when the parliament was convened Walsh was elected as Speaker of the Irish House of Commons. This Irish Parliament was not a success as the various political groupings could not agree on a common way forward and the parliament was dissolved in 1586. The recent rebellions had thrown up a number of diverse political and military groupings and these splits were still apparent in 1585. Nicholas Walsh made an impassioned speech in the Irish House of Commons on the day the Irish parliament was dissolved on 14th May 1586. He criticised all sides of the house for not making a greater effort to reconcile their differences. Nicholas Walsh was very much now of the view that the Irish should have greater control over their own affairs and the failure of the Irish Parliament was therefore a major setback. He persuaded Perrott to outline to Queen Elizabeth that Ireland needed much more control over its own affairs and that renewed efforts should be made to facilitate this aim. These requests however fell on deaf ears and the descendants of Nicholas Walsh in Pilltown were to take a much more direct military approach towards achieving home rule in the following decades.

Nicholas Walsh was appointed to the Irish Privy Council in 1587 which would be equivalent to the present day Irish Council of State. Sir John Perrot was replaced by Sir William FitzWilliam as Lord Deputy of Ireland and FitzWilliam was determined to remove the influence of Perrot from his new regime. John Perrot was convicted of treason and Nicholas Walsh was removed from his position in the Irish Privy Council. In this period Nicholas Walsh became increasingly involved as a judge in serious criminal cases which took place in what were known as the Courts of Assizes, including for example the assizes in Maryborough where he presided as a senior judge in 1693. William FitzWilliam became increasingly aware of the benefits of having Nicholas Walsh on his side due to his legal knowledge and his renowed ability as a negotiator. He persuaded Walsh to come back and act as a mediator in some of the major land disputes that were still ongoing in Munster after the recent rebellions. He also restored Nicholas Walsh to his position in the Irish Privy Council.

Nicholas Walsh of Pilltown was appointed Chief Justice of the Common Pleas on 15th November 1597. The Chief Justice was the most senior judge in the Court of Common Pleas and was therefore one of the highest judicial figures in Ireland at that time. The last Chief Justice of the Common Pleas was Lord Killanin aka Michael Morris who held the title from 1876 to 1887. Killanin was appointed Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1887 incorporating the functions of the Court of Common Pleas which was then discontinued. The year of 1597 was a big year for Nicholas Walsh as, in addition to his appointment as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, he was also knighted by Queen Elizabeth and became Sir Nicholas Walsh. He was officially referred to thereafter as Sir Nicholas Walsh of Pilltown and/or Ballykeeroge.

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 and was succeeded by King James I. The normally sure-footed Sir Nicholas Walsh put himself out in a limb by ordering the Mayor of Waterford to publicly proclaim the accession of James I to the throne as King of England in 1603. He believed that King James I would be sympathetic to Ireland and would be tolerant of religious differences. The Mayor of Waterford was obviously more sceptical of the motives of James I and refused Walsh’s request to proclaim the new king. The Mayor demanded that Catholics should be acknowledged and accepted by whoever succeeded Elizabeth and that King James I should implement his promises for religious tolerance in Ireland. The Mayor had the backing of the inhabitants of Waterford who had good reason to be sceptical of any election promises emanating from the English royal court. In addition they had doubts about Walsh’s real allegiances from his role and activities during the recent rebellions. It was becoming increasingly difficult for Sir Nicholas Walsh to maintain a diplomatic footing in both Irish and English camps. When the Mayor of Waterford refused to proclaim the king it fell on Walsh, as the official recorder in Waterford at the time, to proclaim King James I as the new king. It was not a good decision in the circumstances and Sir Nicholas Walsh was attacked by protesters in Waterford. He was lucky to come out of the city alive and he stated himself that he would have been killed except for the fact that he was related to many of the protesters. Sir Nicholas Walsh spent the remainder of the decade on the legal circuit in Munster and South Leinster until his resignation as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in 1612 due to age and failing health.

Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior of Pilltown had a long and distinguished life which was periodically steeped in controversy. His career was marked by a remarkable political ability to maintain relationships on all sides of the political and religious divide. Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior is sometimes confused in historical records with his son who was also Sir Nicholas Walsh. This is particularly true in stories concerning the alleged “forged commission” from King Charles I which was reputed to have been instrumental in triggering the 1641 rebellion in Waterford. These “forged commission” events happened over twenty five years after the death of Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior and were in fact events associated with his son Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior. The details of the “forged commission” are covered elsewhere in this history under the chapter on the Walshs of Pilltown Part 2.

Nicholas Walsh established a reputation for being an astute political figure with a capacity to resolve difficult political issues. He earned a reputation for being a diligent and hard working judge with a strongly held sense of justice and a determination to eliminate injustice. The close links between Nicholas Walsh and Thomas “Black Tom” Ormond, Earl of Ormond, was a major influence on his life. This relationship was beneficial to both parties and it continued throughout their lives until their deaths within a year of each other in 1614-1615. Any analysis of the life of Sir Nicholas Walsh has to bear in mind the violent and complex situation in Ireland during this period. It could be said that Nicholas Walsh took a pragmatic line in trying to balance the various political, religious and judicial issues of the time. He was strongly supportive of the monarchy and the rule of law as it existed in this period and he showed little sympathy with the various Irish rebellions during his life. As the years rolled on Nicholas Walsh found it extremely difficult to balance the sometimes conflicting roles of Justice of the Queen’s Bench, Irish, royalist, Protestant, closet Catholic, landowner, MP and Anglo-Norman sympathiser. Additionally many of his relatives supported the Irish rebel cause, many of them were Catholics and some of them had their land confiscated after the Desmond rebellions. Towards the end of his life Sir Nicholas Walsh grew extremely disillusioned with the effectiveness of English rule from London and campaigned strongly for more direct rule from Ireland. It would have been one of the great disappointments of his life that the Perrot led Irish House of Commons of 1585 failed due to the inability of the various political interests to come to a satisfactory working relationship. The descendants of Sir Nicholas Walsh Snr of Pilltown later decided that any form of political discussion with England was largely ineffectual and they plunged whole heartedly into rebellion as the only avenue for progressing Irish independence.

Nicholas Walsh Senior firstly married Catherine Comerford and their children included Nicholas Walsh Junior who went on to inherit his father’s estate. After the death of his first wife Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior secondly married Jacquet Colclough who was a daughter of Sir Anthony Colclough and Clare Agard of Tinterne Abbey in Wexford. Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior converted to the Catholic religion before his death in 1615 and was buried in the old French Church in Greyfriars Waterford. His Catholic conversion caused consternation in government and administration circles at a time when one’s religion was a key factor in the whole area of government appointments, status, property ownership etc. It is understood that “Black Tom” Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond who was supported by Nicholas Walsh in his battles with the Earl of Desmond in Munster, also converted to Catholicism before his death in 1614. It is generally acknowledged that many Catholics “converted” to the Protestant religion in this period as this was the only avenue open to them if they wished to attain judicial or political office or to retain their property. As a politician and chief justice in the late 1500s and early 1600s it was politically obligatory that Sir Nicholas Walsh Snr should be a Protestant as Catholics were very much persona non grata in this period. A more detailed overview of Sir Nicholas Walsh Senior is covered in the History of Kinsalebeg: Walshs of Pilltown Part 1 (www.kinsalebeg.com). Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior of Pilltown took over the leadership of the Walshs of Pilltown when his father died in 1615 and we cover the extraordinary life and times of Sir Nicholas Walsh Junior and his sons under the History of Kinsalebeg: Walshs of Pilltown Part 2 (www.kinsalebeg.com).

![]()

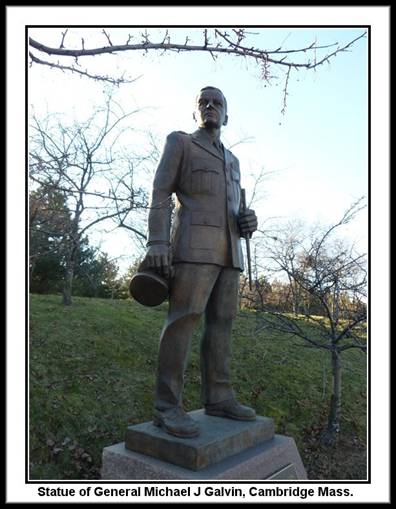

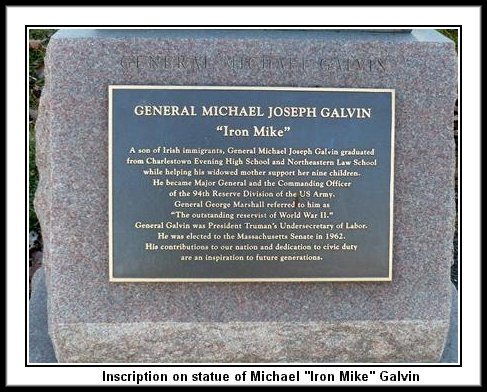

General Michael “Iron Mike” Joseph Galvin (1907-1963) of Monatray & Boston

When President John F. Kennedy needed military advice during the Berlin Wall crisis in 1961 one of military advisers he turned to was General Michael Joseph Galvin. Michael “Iron Mike” Galvin was a Kinsalebeg man or more precisely was the son of a Monatray woman, Bridget Hallahan. He had a distinquished life as an attorney and also in the military. He received numerous military awards including D-Day awards for bravery in Normandy and at the Battle of Bastogne after which he was awarded the Silver Star, 2 Bronze Stars, the Legion of Merit and the French Croix de Guerre. After WWII he was a military advisor and Major General of the Officers Reserve Corp (ORC) and was one of President Kennedy’s key military advisors. He was requested by Kennedy to fly to Berlin in 1961 to establish the exact military position on the ground in Germany. This was an extremely dangerous time in world politics with the volatile Russian leader Kruschev involved in military brinkmanship with the West. This resulted in a series of confrontations and threats that had all the ingredients of another full scale world war. Michael Galvin had in fact served under two earlier American presidents at this time having previously been a consultant to both the U.S. National Security Council and the Defence Department from 1953-1958 during the term of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He had also served as Under-Secretary of Labour from 1949-53 under President Harry S. Truman. Mike Galvin was elected to public office for the first time at the age of 55 when he was elected as a senator for the State of Massachusetts. His public service career was cut short when he died in 1963 at the age of 56 years.

The following is a background to the immediate ancestors of Michael Joseph Galvin commencing with his mother Bridget. Bridget Hallahan was a daughter of Patrick Hallahan and Catherine Walsh of Monatray in the parish of Kinsalebeg, Co Waterford. Patrick Hallahan and Catherine Walsh were married in Youghal R.C. church on 24th January 1867. Patrick Hallahan of Monatray was a son of farmer William Hallahan and Bridget Griffin of Monatray. The ancestral Hallahan home was the still beautiful thatched cottage which is located on the road to Caliso Bay. The cottage is located on the right hand side of the road approximately thirty yards after the final sharp bend in the road before the road reaches its final destination at the beach in Caliso Bay. Catherine Walsh was a daughter of farmer William Walsh and Ellen Condon from Pillmore, Youghal, Co Cork. Bridget Hallahan was one of nine children born to Patrick and Catherine Hallahan in Monatray and eight of the children were alive at the time of the 1911 census. The children were born in the following sequence: Michael was born on 30th November 1867, Bridget was born on 10th April 1869, Mary was born on 5th October 1870, Catherine aka Kate was born on 5th September 1874, Margaret was born on 12th June 1876, Elizabeth aka Eliza was born circa 1877, William was born on 4th January 1881 and Anne was born on 28th October 1883.

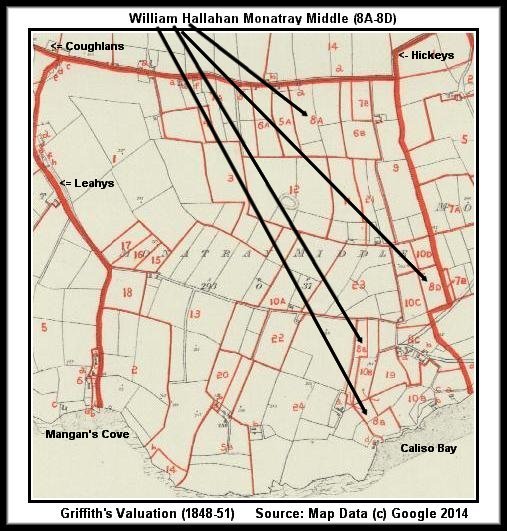

William Hallahan, father of Patrick Hallahan and grandfather of Bridget Hallahan, was a farmer in Monatray Middle, Kinsalebeg, Co Waterford. At the time of Griffith’s Valuation (1848-1851) William Hallahan was leasing a house, offices and land from Mrs Mary Anne Jackson. The total amount of land being leased was approximately twenty acres which was spread over four areas in Monatray Middle as per the following map with Map reference 8A (7 acres, 3 roods, 33 perches), 8B (4a, 0r, 12p), 8C (5a, 0r, 35p) and 8D (3a, 0r, 39p). Maurice Hallahan was also sub-leasing a house to Mary Clancy. Patrick Hallahan inherited the lease of his father’s land around 1893 and in 1899 he was leasing just over twenty acres from the representatives of Philip Jackson Welsh. At the time of the 1901 census Patrick & Catherine Hallahan were living in Monatray Middle with five of their children namely Michael, Mary, Eliza, William and Annie. The family lived in the ancestral Hallahan thatched cottage overlooking the scenic Caliso Bay. Bridget Hallahan was the first of the Hallahan siblings to emigrate to the USA around 1890 and she settled in the Charlestown area of Boston where she worked as a housekeeper and cook. She was followed to Charlestown in later years by Margaret, Catherine (Kate) and Eliza. Kate Hallahan emigrated from Queenstown on 27th September 1901 on the ship New England and resided initially with her sister Bridget Galvin nee Hallahan at 51 Austin Street in Charlestown Boston. Four of the children remained in Ireland namely Michael, Mary, William and the youngest daughter Anne aka Annie. Michael, the eldest in the family, never married and Mary also did not marry. Anne Hallahan married Cornelius Walsh of Drishane near Killeagh Co Cork and they had a number of children. One of their daughters, Mary Kate Walsh, married William Kearney from Conna and their descendants still reside in the area. William Hallahan, the second son of Patrick & Bridget Hallahan, married Mary Clarke who was a daughter of Declan Clarke and Julia Clancy. William Hallahan was an outstanding Gaelic footballer in a period when Kinsalebeg and subsequently Kinsalebeg & Clashmore Gaelic football teams were very successful on the playing fields of Waterford. Kinsalebeg had played in the first ever senior football final in Waterford when they were beaten by Ballysaggart in 1885 but came back to win their first senior football county final in 1886 when they beat Kilrossanty in the final. They went on to win another senior football county title in 1890 when they beat Dungarvan in the county final and then lost the 1891 county final to Shandon Rovers of Dungarvan. Next door neighbours Clashmore also had a very successful period at the turn of the century when they won the senior football championship on five successive years in Waterford in the period from 1903 to 1907. The Hallahan family of Monatray produced a number of great Gaelic footballers down the years but William Hallahan was probably the best known of all of them. He was known as William “Whitehead” Hallahan due to his light coloured blond hair and his exploits as a high-fielding Gaelic footballer were legendary in Kinsalebeg. William “Whitehead” Hallahan and Mary Clarke had no children and he had a long life until his death in the 1960s.

Bridget Hallahan married James Galvin in St Mary’s R.C Church at Bunker Hill Charlestown on the 30th June 1898 and they initially lived in 62 Union Street. James Galvin was born on 24th February 1868 in Clonakilty, Co Cork and emigrated to Boston on the 15th May 1886 at eighteen years of age. They went on to raise ten children and their first child Mary Catherine aka Mae was born on 30th December 1898; John was born on the 21st March 1900; Ellen aka Babe was born on the 5th March 1902; William aka Bill after his grandfather was born on the 30th January 1904; James was born on the 17th November 1905 but unfortunately died of pneumonia at five years of age. Their 6th child Michael Joseph was born on the 7th September 1907 and the family moved to 51 Austin Street shortly afterwards where Margaret aka Peg was born on the 26th April 1909. The family moved to 30 Chapman Street where Anne aka Annie was born on the 19th November 1910. James Galvin was a freight handler with the railroad at this point.

Michael Joseph Galvin as outlined above was born on 7th September 1907 in Boston. He had a distinguished legal, military and political career until his premature death in 1963 at the age of fifty-five years. He grew up in a tough tenement environment in Charlestown and the financial circumstances would have been difficult with ten chidren in the family. Michael J. Galvin was very much a self-driven individual who apparently had a strong work ethic coupled with a good attitude to life. He started his working life as a messenger boy for the Western Union while he was still at school. He completed his grammar school education in 1921 at which stage he was working on general office duties for the prestigious New England law firm of Herrick, Smith, Donald & Farley. He took up evening further education studies at Charlestown Evening High between 1922 and 1926. The partners in Herrick, Smith & Co law firm encouraged him to take up legal studies and he took up further night studies at Northeastern University & School of Law. He graduated from Northeaster in 1932 and was admitted to the offices of Herrick Smith as an associate lawyer. He then studied for the Bar exams which he passed on 2nd November 1932. Michael J. Galvin went on to have a distinguished career as an attorney working mainly in the area of company acquisitions, mergers and consolidation. He married Eleanor Stevens in St. Francis de Sales Church in Charlestown on the 7th June 1926. They had five children namely Patricia (born 24th Aug 1937), Noreen (born 10th Oct 1939), Priscilla (born c 1941), Michael (born Nov 1942) and finally Gail (born March 1947).

The military career of Michael Joseph Galvin aka “Iron Mike” commenced in 1926 when he enrolled in the Enlisted Reserve Corps. His military and legal careers were carried on in parallel throughout his life. He was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant in the Infantry Officers’ Reserve Corps (ORC) in December 1930 and his military career is largely associated with the ORC from that point onwards. He progressed rapidly through the ranks and became 1st Lieutenant ORC (1934), Major (1942), Lieutenant Colonel Army Reserves (1942), Colonel Cavalry ORC (1945), Brigadier General and finally Major General ORC in December 1960. His active military assignments included tank company commander in the 2nd Armored Division (1941-42), Major to Lieutenant Colonel in the 6th Armored Division (1942-46), 94th Infantry Division, Massachusetts (1945-49) and Brigadier General in 94th Infantry Division (1958-63). Most of his combat experience was in Europe during WW2 and he was involved in campaigns in Brittany (1944), Brest (1944), Luneville & Lorient (1944), Seine Valley (1944), Saar Valley (1944), Ardennes (1945), German Campaign in 1945 including Rhine Plain, Frankfurt, Kassel and Mulde River. He received numerous military decorations and citations during his military career including the American Defence Medal, Bronze & Silver Star medals and numerous campaign awards during his combat period in Europe during WW2. For D-Day bravery at Normandy and at the Battle of Bastogne he was awarded the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, the Legion of Merit and the French Croix de Guerre. He spent 302 days on the front lines in General Patton’s Third Army during what was known as the European Theatre of War campaign of WW2. During this and other military campaigns and exercises he won high praise from General Patton which was no mean feat bearing in mind Patton’s well known reservations concerning reserve troops and indeed Irish Catholics. On the instructions of General Grow he chronicled the only Division history of WW2 combat from his experiences during this campaign in a document titled Combat History of the Super Sixth. This document detailed in full the actions of the 6th Armored Division during WW2 and ensured that their exploits and military successes would not be forgotten and indeed would be used for training future military regiments. Michael J Galvin was described by General George C. Marshall as “the most outstanding Reservist to serve his country in World War II”. Mike Galvin was appointed to high ranking positions after WWII by both President Truman & President Eisenhower. He was also a military advisor to President John F Kennedy and during this period he was involved in a number of, sometimes public, confrontations with Defence Secretary Robert McNamara. McNamara was perceived to be arrogant and “accident prone” by experienced military personnel and they believed that he made a number of serious strategic military errors during his period as Defence Secretary.

Bridget Galvin nee Hallahan from Monatray died on the 28th March 1962 at the age of 93 years. Bridget’s death was followed shortly by that of her son, Michael “Iron Mike” Galvin, who died in 1963 and was buried in Arlington Cemetery. A statue of General Michael Joseph Galvin (1907 - 1963) is located at Galvin Memorial Park, New Rutherford Avenue, in Cambridge, MA and the park itself is also named in his honour. Extensive details on the life of Michael Galvin are available in his biography1 written by his daughter Priscilla.

Now it was no surprise to the residents of Kinsalebeg that three American presidents had turned to a Kinsalebeg man for advice in difficult military situations. Indeed the book on military strategy could have been written in Kinsalebeg when one considers the myriad of military encountes involving Kinsalebeg natives over the centuries. It was no surprise to us that Cromwell scurried quickly through Kinsalebeg and across the ferry to the safe haven of Youghal in 1649! He was undoubtedly acutely aware of the dangers of outstaying his welcome in this part of Waterford! It is interesting to note therefore that three American presidents of the 20th century were happy to involve a son of Kinsalebeg in their military decision making! The following is a summary of the locations of some of the military confrontations involving men from Kinsalebeg that this History of Kinsalebeg has thrown up. We start in 864 A.D when the powerful Deise tribe from the West Waterford area attacked and destroyed the Norse fort at Youghal and we finish with the Pilltown Ambush on the 1st November 1920 during the War of Independence.

Military encounters involving men from Kinsalebeg include the Deise Norse attack (864), the 16th century Desmond rebellions, the 1641 rebellion, Capture of Dungarvan (1643), Siege of Youghal (1645), Siege of Pilltown (1646), Siege of Derry (1688), Siege of Cork (1690), Siege of Limerick (1690), Siege of Ennis (1960s - we should really exclude this even though some of the set dances in the old school at Pilltown in the 1960s could get fairly physical!) and the 1698 rebellion. We can also include the Battle of Cappagh (1642), American War of Independence (1775-83), Crimean War (1853-56), Indian Rebellion (1857-58), Abyssinian Campaign (1867-68), Boer War (1880-1902), various WWI land battles at Ypres, Neuve Chapelle, Aubers, Festubert, Givenchy & Loos, Arras (1917), Cambrai (Nov 1917), Bourbon Wood (Nov-Dec 1917), Cambrai (Dec 1917), Messines (1917), Passchendaele (1917), Battle of Lys (1918), Russian Civil War (1917-1922), War of Independence (1919-21) and the Pilltown Ambush (1920). If we move on to military campaigns at sea then we can track Kinsalebeg naval men involvement in multiple campaigns such as the Battle of the Falklands (1914), the Battle of Jutland (1916), the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipolli (1915-16), the Baltic Campaign (1918-19), East Indies & China Stations and a multitude of other actions particularly during World War I. They travelled hundreds of thousands of miles across every sea and ocean including the North Sea, North & South Atlantic, Irish Sea, Mediterranean, Pacific, East Indies, China, Baltic and East Africa. We now add to the above list the military experiences of another son of Kinsalebeg namely Michael “Iron Mike” Joseph Galvin of Monatray & Boston.

1 High Ideals: The Life of Michael J Galvin by Priscilla G. Watkins. Published 2008 AuthorHouse.

![]()

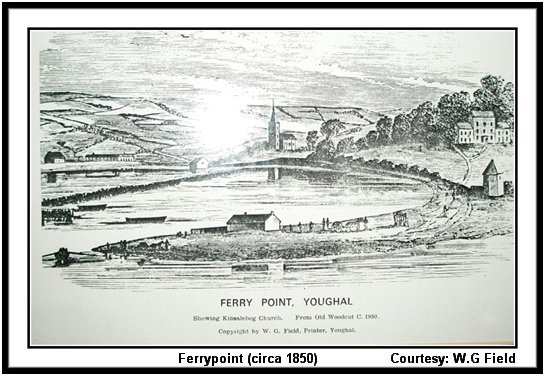

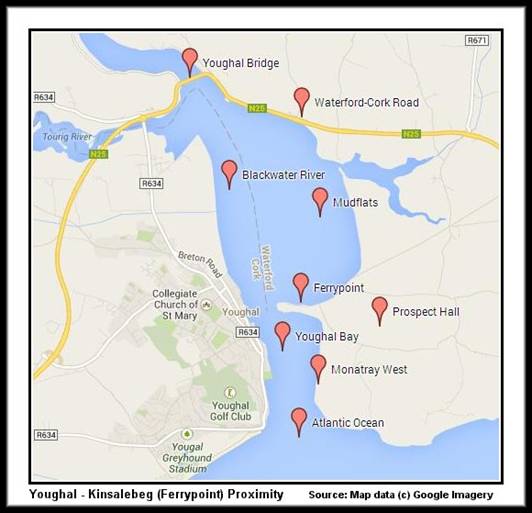

Duncannon Sunk by Artillery Fire from Ferrypoint (17th July 1645)

The Irish Confederate Wars or Eleven Years’ War were still in full swing in 1645 and there was no immediate likelihood of an end to the hostilites. The war had started in 1641 and was essentially a series of civil wars in Ireland, England and Scotland which were all under the jurisdiction of King Charles I. It was primarily a war between the Royalist supporters of King Charles I and the Parliamentary supporters of Cromwell who had risen against the king. As the war proceeded all sorts of unusual alliances were established and there were frequent changes of sides depending on the circumstances on the ground at the time. In Ireland the war was fought between the Irish Catholic Confederate forces and the Parliamentary forces. The Confederate forces were essentially the native Irish Catholics with some support from Anglo-Norman landlords who were long time residents in Ireland and who were typically strong royalist supporters. It was an unusual situation in Ireland in that the Irish Confederates were essentially fighting in support of the king.

Youghal was under siege from from the Irish Confederates in 1645 and the focus of this article is the July 1645 period. The town was at this time under the control of Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery but better known as Baron Broghill. Broghill and the Boyle family of Lismore were traditionally staunch royalist supporters but were persuaded by Cromwell to switch their support to the Parliamentarians and as a result Broghill took up a leading military position in the Parliamentary forces in Munster. Cromwell was a persuasive individual and no doubt the possibility of “losing the head” in a real sense was a very real prospect for Broghill if he chose to ignore the “advice” of Cromwell. Broghill was not in Youghal in July 1645 as he was away in England seeking support and supplies to assist in the war against the Irish Confederates. He left Youghal under the control of his subordinate Sir Percy Smyth of Ballynatray who was assistant governor in the town and who was in for a torrid time in the absence of Broghill.

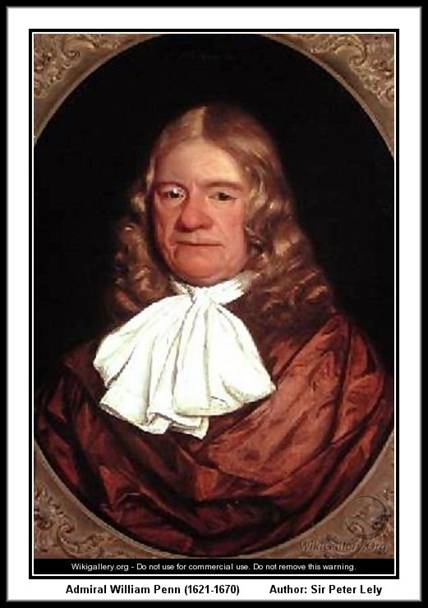

Lord Inchiquin (aka Murrough O’Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin, “Murrough the Burner”) was in charge of the Parliamentary forces in Munster in 1645. On the 5th July 1645 Inchiquin instructed Admiral William Penn to bring naval support to assist in the relief of Youghal where the inhabitants were suffering greatly as a result of the siege. Admiral Penn was father of William Penn Junior who in later years went on to become the Quaker founder of the state of Pennsylvania in the USA. The Irish Confederate forces involved in the siege of Youghal were led by Castlehaven (aka James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven). Castlehaven had some heavy artillery and forces on the Ferrypoint side of the harbour from where he was able to control entry to Youghal and to the important River Blackwater. Admiral Penn set sail from Kinsale to Youghal on 8th July 1645 and arrived in Youghal later that day. On the morning of the 9th July Penn went ashore in Youghal and met up with the deputy governor of the town, Sir Percy Smyth, who advised him of the perilious state of affairs in Youghal. Smyth instructed Penn to place the merchant-ship Nicholas in the bay at the south end of the town and the Duncannon frigate at the north end of the town. Admiral Penn hit his first setback in Youghal when he was returning to his barge after the visit to Percy Smyth. Penn answered the governor’s five gun salute with a three gun salute from his own barge but there was an accident during the firing of the last gun. According to Penn:

“at the firing of the last gun, the piece not being well sponged, took fire, as one of our men was ramming home the cartridge, and so unhappily blew off one of his hands.”

On the 16th July 1645 the Irish rebel Confederate forces under Castlehaven were seen to be planting additional long range guns in the hill of Monatray on the east side of the harbour. Penn’s forces attempted to fire on the rebel artillery positions on the Ferrypoint side of the harbour but they were outside the range of their guns. During the night of 17th July Castlehaven had placed three additional guns on Ferrypoint and commenced to fire on the Duncannon frigate when morning broke. The Duncannon was sunk in the exchange of gunfire between the ship and the artillery on Ferrypoint. However the exact circumstances surrounding the sinking were different in the later reports of Penn and Castlehaven. According to Castlehaven the Duncannon was sunk in the first salvo of gunfire from Ferrypoint. Penn however maintained that the ship sunk as a result of an explosion in the powder room. The following is Penn’s description of events as detailed in his memoirs:

“By break of day, the enemy had made a fort of cannon-baskets on the east side, opposite to the town fort; and having drawn down three guns into their work, shot at the Duncannon frigate, she at them again; but by an un-expected accident (as we after were informed) the powder of their store took fire; which being blown up, she immediately sunk, and being but little more water than she drew, her stern was above water, when her bilge lay on the ground. All those which were afore the mast suffered, in number 18, with one woman; she, with two of the 18, being, as was reported, in the powder-room, when the powder took fire. Seven more of the company were very much scalded and bruised; but, God be praised !, we have hope of their recovery.”

Admiral Penn therefore lost 18 men in this encounter with the rebel Confederate forces on Ferrypoint or seventeen men and one woman to be precise. It is unusual that a woman was among the 18 casualties of the sinking of the Duncannon as it was not common to have women manning guns or indeed to be present on war ships in those days. According to Penn the woman was in the powder-room with two men when the powder took fire resulting in the blowing up of the ship. The incident as outlined by Penn raises more questions than answers. Firstly it is a coincidence that an accident in the powder room occurred at the same time as the ship was under heavy fire from the Confederates on Ferrypoint. Secondly the question arises as to why a woman was present on the ship at the time and more critically what she was doing in the gunpowder room. Is it possible that she may have misinterpreted the Powder Room sign on the door of the gunpowder room? What started as a possible innocuous trip to powder the nose and have a quick smoke ended up in a horrible tragedy as the gunpowder caught fire and the ship blew up with eighteen deaths. We will never know the real facts of the sinking of the Duncannon but there is no doubt about the accuracy of the artillery fire from Ferrypoint as other incidents at the time confirm. We will have to take the Castlehaven account of the Duncannon being sunk as a result of artillery fire from Ferrypoint as being the most credible description but the “woman in the powder room” version is a more intriguing story!

The bad luck of Admiral Penn and Percy Smyth were however not at an end with the sinking of the Duncannon. Later on in the afternoon of the 17th July 1645 Admiral Penn, together with Captain Philips, went ashore in Youghal to visit the deputy governor Percy Smyth in order to decide the next course of action. During the visit to Youghal they viewed the arrival of two Confederate forces boats in the north side of the harbour. The boats had come down the River Blackwater and were laden with provisions and ammunition for relief of the Confederate forces on the Ferrypoint side of the harbour. Admiral Penn viewed this as an opportunity to recover some respect after the earlier setback with the Duncannon. He ordered his barge to pursue the Confederate boats but they were forced to abandon the pursuit as they came under heavy fire from Ferrypoint. Admiral Penn was viewing these events from the quay wall on the Youghal side of the harbour. He was accompanied by the deputy governor Percy Smyth, Lieutenant Colonel Loftus, Lieutenat Colonel Badnedge and some other soldiers. The Confederate forces on Ferrypoint saw a great opportunity to inflict further damage on Penn and turned their artillery fire on the quay in Youghal. Lieutenant Colonel Loftus and Lieutenant Colonel Badnedge, together with two other soldiers, were killed by the artillery fire from Ferrypoint. The only two to escape the gunfire were William Penn himself and the governor Percy Smyth who both made a hasty retreat. The following was Penn’s account of the latest set of events:

“the enemy made a most unhappy shot from their fort on the other side of the water, which killed the two lieut.-colonels, and two soldiers; five others were carried away, supposed to be dead, but were presently found indifferent well, having no great hurt. Only the governor and myself escaped untouched, but with the stones which flew thick about our ears; for which deliverance God make me for ever thankful! We quit the fort, and went into a house hard by. I requested Sir Percy Smith to despatch a messenger with this sad news to my Lord of Inchiquin, as also for some other officers in the room of those gentlemen that were slain; which he did the same night.”

Admiral William Penn was lucky to survive events of the 17th July 1645 but Penn’s bad hair day was still not at an end. The men injured on the ill-fated Duncannon were brought aboard the Entrance and Penn ordered the Duncannon’s captain and gunner together with carpenters from the Nicholas to go back on board the semi-submerged Duncannon to salvage the sails, rigging and guns. The Duncannon’s crew refused Penn’s orders to go back on board the ship. They maintained that they had lost everything already and did not wish to lose their lives as well from enemy gunfire coming from the Ferrypoint side of the harbour. The following morning Penn sent in his barge to assist the Duncannon crew in the salvage operation. The Duncannon crew still refused to cooperate and Penn eventually had to order six of his own gunners to salvage what they could from the stricken Duncannon. They eventually retrieved a couple of the best guns and some ammunition.

On 19th July 1645 Penn became aware that the Confederate forces had placed another gun on the eastward point of the harbour’s mouth and were now firing on the ship Nicholas, captained by Captain Bray, which was anchored on the south side of Youghal harbour. The exact location of this gun is unsure but we assume the Confederate gun was placed somewhere between Ferrypoint and East Point on the hill of Monatray across from the mouth of Youghal harbour. The firing accuracy from the Waterford side of the harbour continued and Penn incurred additional casualties with two men killed and two injured on the Nicholas. This is Penn’s account of the event:

“19th – In the morning, by break of day, the enemy had planted a gun on the eastward point of the harbour’s mouth, and made divers shot therewith at Captain Bray, he at them again; but before he could get his anchors on board, two of his men were killed and two hurt by the rogues, who shot him between wind and water, and several times in the hull. At last, weighed, set sail, and, coming forth, anchored by us”.

The siege of Youghal continued for a number of months with varying degrees of success on both sides. The Youghal garrison was able to get much needed supplies on a number of occasions by running the gauntlet of the Confederate forces guarding the harbour entrance. On the 7th August 1645 William Penn left Youghal and sailed for Cork. A few days later he was relieved of command of his ship Entrance by the arrival of Captain John Crowther who also took over as vice-admiral of the fleet. Admiral William Penn did not remember fondly his visit to Youghal and it is unlikely he ever returned to take a holiday in Ferrypoint after the welcome he received from the rebel forces on the Waterford side of the harbour. In September 1645 Lord Broghill had effectively relieved Youghal when he arrived with troops from England. Broghill was never shy in blowing his own trumpet and outlined the details to William Lenthall who was Speaker in the British House of Commons in 1645. Broghill stated that the siege was at an end due to his own actions and that the great guns, including any remaining on Ferrypoint, were now silenced. Some of his words to William Lenthall are recorded as follows in The Historic Annals of Youghal:

“Youghal was relieved after three months’ siege by the forces brought over by Broghill. The enemy drew off 5 or 6 miles. The besieged, by a brave sally a fortnight ago, routed the enemy, seized 2 great guns they had planted at both sides of the harbour”.

Further details of the Siege of Youghal and Ferrypoint including the arrival of Confederate leader General Preston are covered elsewhere in the History of Kinsalebeg at (www.kinsalebeg.com).

![]()

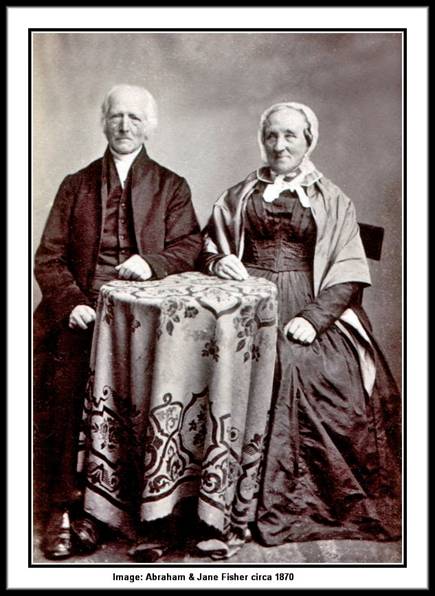

The Growth & Decline of Fishers’ Mills at Pilltown

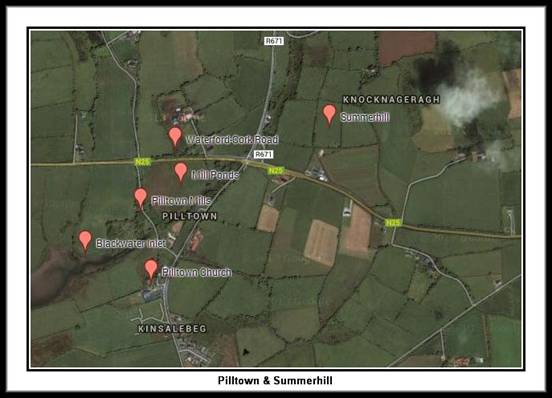

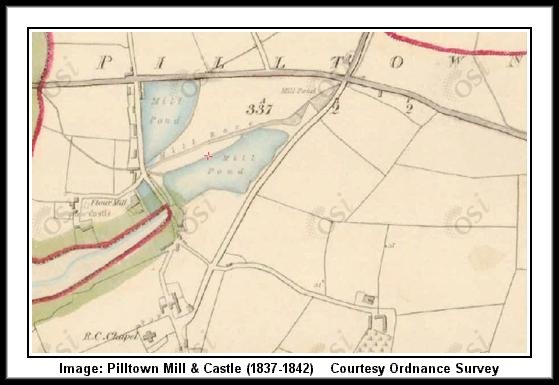

The ruins of Fishers’ Mills of Pilltown are still visible today even though the mill itself ceased production in the latter end of the 19th century. Fishers’ Mills played a significant part in the industrial history of Pilltown and it was the largest single employer in the area in the 19th century. The mills at Pilltown were run by the Fisher family who had a long association with the Youghal area commencing with the arrival of Reuben Fisher from Southwark in 1692. The members of the Fisher family most closely associated with the milling business in Pilltown were Reuben Fisher, his son Abraham Fisher and finally Abraham’s son Peter Moor Fisher. They were members of a family of largely Christian religious movements known collectively as The Religious Society of Friends but were more frequently referred to as Quakers or Friends. Reuben Fisher took out a lease on land and buildings in Pilltown from Deaglan Connery on the 24th September 1795 and the Fisher milling operation in the area commenced around that time. The lease document indicated that there was already a mill on the land which was known as the Mill of Piltown but it would appear that the mill had ceased operations and there is no indication as to when the mill was previously in operation before the arrival of the Fishers. The lease stated:

“Deaglan Connery did demise unto the said Reuben Fisher all that and those the Mill of Piltown aforesaid with the Mill House & Kiln with a field near the same wherein was there a slated house ...” [24th Sept 1795].

There are references to the presence of a medieval mill in Pilltown for centuries before the Fishers and it is probable that it was in existence in the period before 1583 when the Earls of Desmond (Fitzgeralds or Geraldines) were the major landowners in this part of Munster. Sir Nicholas Walsh Snr, of the formidable family known as the Walshs of Pilltown, obtained the land around the parish of Kinsalebeg when the Desmond estates were broken up after the 1579-1583 rebellion. Pilltown Castle and the The Mill of Pilltown were already in existence when the Walshs became the resident landlords and the Civil Survey of Waterford in 1655 has the following reference to Pilltown:

“upon wch standeth an old battered Castle with a large bawne, good habitation and a mill worth £10 by ye yeare” [1654-1655].

The history of the Fishers is covered in detail elsewhere and this article is confined purely to an overview of the scale of the milling operation in Pilltown from 1795 to 1865. We get a good indication of the scale of operations at Fishers’ Mills in Pilltown from the description of the mill in the auction documents when the Fisher properties were eventually put up for auction via the Landed Estates Court in 1865 due to financial difficulties. The Landed Estates Courts were a kind of 19th century equivalent to NAMA and were set up to sort out the financial difficulties encountered by many of the large estates in the period following the famine.

The mill at Pilltown was capable of handling the milling of both wheat and Indian corn. It was capable of being operated by both water and steam with the steam engine being primarily used as auxiliary backup power. The processing capacity was of the order of five hundred barrels of wheat and about fifty tons of Indian corn per week. The mill contained in total six pairs of French mill stones with five of these being used for wheat milling and the sixth for milling the Indian corn. There was also a pair of twenty four foot long silk dressing machines and two barrel screens for cleaning the wheat with an additional two barrel screens for cleaning the Indian corn. The iron water wheel was a massive 40 feet in diameter and from a technical point of view was it was capable of operating as both an overshot and a breastshot wheel. The storage capacity at the mill was about 3,000 barrels of corn and boats know as lighters were used to discharge wheat and corn directly to the mill and also to transport milled flour to/from nearby ports such as Youghal, Cappoquin, Dungarvan, Cork and Lismore. The Blackwater River has an inlet leading to the old mill and it was possible for boats to discharge their cargo at the mill and return to the Blackwater and Youghal Bay on the same tide. The mill was a big mill by any standards with a capability of processing close to 100 tons per week between wheat and Indian corn. At approximate corn rates in the 1840 to 1850 period we are probably taking about a mill with a turnover in excess of 100,000 pounds sterling per annum. If we roughly equated this to today’s currency then we would be talking about a mill with a turnover in excess of 10 million euro per annum.

The Fishers had over 300 acres of land in the Piltown & Summerhill area in the early part of the 19th century. The bulk of the land was in Knocknageragh or Cnoc na gCaorach (“Hill of the Sheep”) which is more commonly known as Summerhill. This is the land on the left hand side of the road just past Pilltown Cross as one drives from Youghal towards Dungarvan. There were at least twenty nine houses on this land which were being leased out by the Fishers. The remaining land and property of the Fishers was in Pilltown itself and was mostly associated with the operation of the mill. The corn mill itself was located on the left hand side of the road at the base of the side road just above Piltown Church which joins up with the old Kinsalebeg Post Office. The Fisher house, mill, kiln and offices were on a three acre site and there was a small quay to provide cargo access to the Blackwater River and Youghal Bay – there was another quay further along the river inlet towards Pillpark next to the building commonly known as The Cellar. The Cellar and nearby quay were used for storing and shipping corn and other goods for the nearby mill and were also apparently used at one time for storing & shipping of ice blocks from the ice houses in Garranaspick. The quay was later used for shipping bricks from the nearby, shortly lived, brickwork business of the Farrells of Youghal in the early part of the 20th century. In addition to the mill and storage premises there was also a large dwelling house close to the mill consisting of two sitting rooms, five bedrooms, kitchen, pantries etc and an enclosed garden. The land on which the milling business was being carried out was owned by the Kennedy family who were leasing it to the Connery family until Deaglan Connery transferred the lease to Reuben Fisher in 1795.

The mill ponds and mill race were on the opposite side of the road to the mill itself and occupied a total of around 17 acres which was being leased by the Fishers from the Kennedys. The land occupied by the mill ponds was the triangular piece of land within the roads from Piltown Church (just above) to Piltown Cross and back to the old Kinsalebeg Post Office. Within that area were two large mill ponds and one small mill pond. The largest mill pond occupied about 6 acres and was on the left hand side of the road from Piltown Church to Piltown Cross. The second mill pond was on the raised land on the right hand side of the road between Healy’s Pub and Kinsalebeg Post Office and seemed to occupy about four acres. The mill race ran between the two large mill ponds and this water source also ran through the Fisher lands in Summerhill or Knocknageragh. A smaller mill pond was located at the angle of land at Piltown Cross itself. In the period around 1855 there were over forty houses in total in Pilltown and a large number of them were occupied by people who worked in Fishers’ Mills. Most of these houses are no longer in existence or are now derelict.

The mill was a major employer in the Kinsalebeg area and of course also provided a convenient grain output for farmers in the area. The Fishers ran into severe financial difficulties in the 1860s. The mills were eventually forced to close permanently when Peter Moor Fisher was declared bankrupt in 1867. The various Kinsalebeg and Youghal properties of the Fisher family eventually finished up for sale in the Landed Estates Courts including all the land, buildings and equipment associated with the milling operation in Pilltown. The mill was being sold as a going concern and there is no doubt that the relatively modern milling facility in Pilltown could have continued operations under new ownership. However these were difficult post famine times and the milling operation never restarted in Pilltown.

Abraham Fisher and his son Peter Moor Fisher emigrated to Neath in Wales where Abraham died in 1871 at eighty seven years of age. Peter Moor Fisher died in Neath in 1899 at ninety one years of age. The Fisher family contributed enormously to life in Youghal and Pilltown for a couple of centuries from 1692 onwards. Their Quaker religious beliefs were the driving force behind their strong views on social justice and their commitment to philanthropy. Apart from their multiple business activities various members of the family were involved in a plethora of activities including famine relief, anti-slavery, women’s rights, abolition of church tithes, rights of indigenous peoples, social reform, land reform, poor law relief and aborigine protection. We cover in detail the lives of various members of the Fisher family elsewhere in this history at www.kinsalebeg.com ranging from the suffragette activities of Anne Marie Haslam nee Fisher to the founding of the Munster Express by Joseph Fisher, both offspring of Abraham Fisher of Fishers’ & Pilltown mills.

![]()

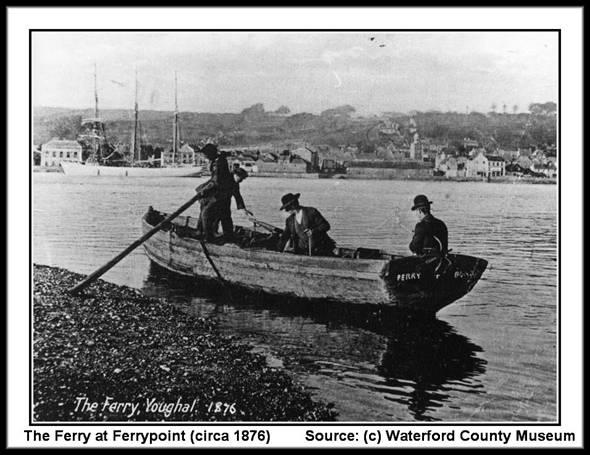

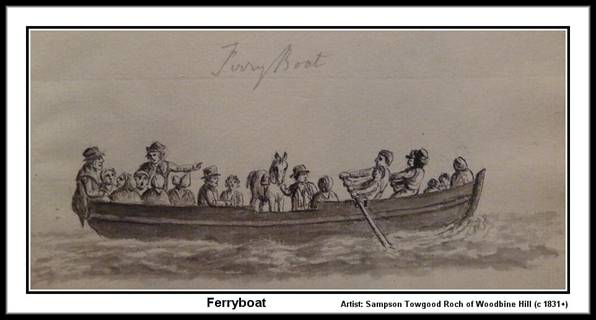

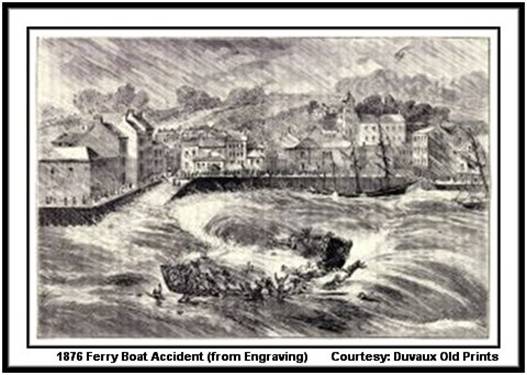

Major Ferry Boat Accident at Ferrypoint (30th Sept 1876)

Thirteen people lost their lives in the last major ferry boat accident between Youghal and Ferrypoint which occurred on Saturday 30th September 1876. The tip of Ferrypoint is a short few hundred metres from Youghal and the ferry boat journey itself took no more than five minutes. However the shortness of the distance masked what is an extremely dangerous stretch of water where the fast moving River Blackwater meets the Atlantic Ocean in the narrow channel which separates the counties of Waterford and Cork. The intersection of fresh and salt water produces turbulent eddies and swirling water which spells danger for boatmen and swimmers alike even in relatively tranquil weather conditions. The Youghal to Ferrypoint ferry was the main mode of transport between Waterford and Cork in this area for hundreds of years before the completion of the first Youghal Bridge in 1832. This ferry service was in operation at least as far back at 1288 when the ferry rights were in the ownership of the Manor of Inchiquin and ran for close to seven hundred years until the closure of the service in the 1960s. There were numerous ferry boat accidents during this period with the Earl of Cork reporting an accident on the 14th September 1616 when thirty people were drowned. Another major accident took place on the 18th February 1837 when up to twenty people lost their lives and this accident resulted in the establishment of the Youghal Lifeboat Station in 1839.

The ill-fated ferry left Youghal for Ferrypoint at 4.30 pm on Saturday 30th September 1876. The weather conditions were poor and were described as follows:

“At the time of putting out from shore the tide was on the turn, with half a gale blowing from the south-east, causing a heavy sea on the portion of the river across which the ferry boat had to pass, and it was also raining very hard.”

There were twenty four people on board the four-oared ferry which was made up of twenty one passengers and three boatmen. There was also a quantity of goods on board including potatoes, meal and other goods in the possession of passengers after a days shopping in Youghal. Passengers and witnesses later reported that the ferry was already taking in water before it left the relative tranquility of the walled inner harbour. As soon as the ferry hit the open seas outside the harbour it was struck by some heavy waves and sunk immediately according to eye witnesses and survivors. All the occupants of the ferry were thrown into the water and five or six nearby fishing boats immediately set out to rescue the passengers. They managed to rescue eleven of the twenty four people on board but thirteen people lost their lives. Queries were later raised regarding the wisdom of having such a heavy load on board particularly in the poor weather conditions. The weather was undoubtedly a major factor in the cause of the accident but a number of other factors were raised in the subsequent inquests and court cases including overloading of the ferry, the poor condition of the ferry itself and finally the sobriety of the head boatman.

The following we believe is an accurate list of the casualties and the survivors of the ferry boat accident of the 30th September 1876. This has been compiled from a combination of death certificates, inquest details, newspaper reports and the subsequent inquiry into the accident. A number of the bodies were never found which added to the confusion at the time of the accident. The final confirmed death toll was the following thirteen people:

(1) Ellen Budds: It is recorded on inquest death certificate that she was aged 34 and was a farmer’s wife and the cause of death was drowning. It was also mentioned by the examining doctor that she was in an advanced state of pregnancy at the time of her death. The inquest reports into the deaths of six other victims were dated 13th April 1877 and were as follows:

(2) Michael Carey aged 58, married, farmer;

(3) Bridget Connery nee Wynne aged 50, married, farmer’s wife, from Rath. She was a sister of Robert Wynne who also drowned in the tragedy.

(4) Hanorah (Hanna) Keane aged 30, married, farmer’s wife, from Springfield.

(5) John Shanahan aged 35, married, farmer.

(6) Mary Lincoln aged 22, spinster, servant.

(7) Robert Wynne aged 63, married, farmer, from Rath. He was a brother of Bridget Connery who was also drowned. Robert Wynne had just returned to Ireland after living in the USA for many years. Robert and his sister Bridget were in Youghal to get supplies for his home-coming party but both were tragically drowned on the return trip.

All the above deaths were recorded as being accidental drowning at Youghal Ferry. It would appear that a number of bodies were not recovered after the accident and there was therefore no death certificate or inquest for these casualties. The other casualties appeared to be the following:

(8) William Carthy/McCarthy, a boatman from Youghal.

(9) David (Davy) Mahony, a boatman from Youghal.

(10) Patrick Keane from Mortgage.

(11) Michael Keane from Ardo.

(12) John Tracy/Treacy from Aglish.

(13) Margaret Foley from Grange.

(14) The status of a Richard Shanahan is unknown even though one report indicates he was drowned – it is probable that his name was mixed up with that of John Shanahan who was drowned or with Richard Staunton who appeared in one report as a casualty.

The following is the list of survivors of the ferry boat accident of the 30th September 1876. This was compiled from the various inquiries, court cases and newspaper reports after the accident:

(1) James Lynch from Summerhill whose mother refused to go on the ferry as she felt it was too dangerous.

(2) Michael (Mick) Fitzgerald, husband of Kate FitzGerald, a farmer from Ardo. He was a witness at the later inquiry into the accident.

(3) Catherine (Kate) Fitzgerald, wife of Michael Fitzgerald above.

(4) Thomas Burke from Prospect Hall.

(5) Robert Gleeson, who was on the bow oar but appeared to be just a passenger who decided to help on the oars.

(6) Edward Gorman, the head ferry boatman from Youghal who was later convicted of manslaughter.

(7) Mary Whelan

(8) Mary Foley

(9) Mrs Catherine McCarthy

(10) Edward Staunton

(11) Mary Keeffe

The following are some additional notes on passengers of the ill-fated ferry of the 30th September 1876.

(a) Kate Fitzgerald was lucky to survive the ferry accident as she apparently went under the water a few times but was eventually rescued together with her husband Michael. In the 1901 census the Fitzgeralds were still living in Ardoginna and the following were the family members Michael Fitzgerald aged 58, wife Kate Fitzgerald aged 54 and children Declan aged 20, Edmund aged 17, Maggie aged 17, Hanna aged 16, James aged 14, Thomas aged 12 and Con aged 10. The following newspaper report in the Cork Examiner describes Kate Fitzgerald’s rescue: “One woman, in particular, distinguished herself by her struggles for life. On being precipitated into the water, she was struck on the head by a wave and disappeared from view, but in a few seconds her hand was seen above the water and she succeeded in grasping an oar. She had scarcely time to breathe before she was knocked off the oar by another wave, and would in all probability have been drowned, but for the timely arrival of Kelly’s boat which took her up. We are glad to be able to state she was sufficiently recovered yesterday to go home.”

(b) Thomas Burke aged 74, labourer, was still living in Prospect Hall in 1911 census with his wife Mary Burke aged 74. According to the census they were married for fifty years at that time and had eight children of which only two were still alive in 1911.

(c) Questions were raised as to the sobriety of Edward Gorman, the head boatman, at the time of the accident. Witnesses at the inquiry indicated that they felt he was capable of carrying out his ferry duties even though it was acknowledged that he may have had some “drink taken”. Michael Fitzgerald, one of the passengers and an inquiry witness, said he had given him a half noggin of whiskey in Connor’s pub earlier on the fatal accident date but there was no proof he had actually drunk it. Edward Gorman was later convicted of manslaughter and given twelve months hard labour. It is apparent from the inquiry reports that he was requested to return the boat to the dock on a few occasions before the accident but declined to do so. The ferry boat lessee Edward Connors received 18 months hard labour when he was also convicted of manslaughter.

(d) Two of the boatmen, who were both from Youghal, also lost their lives in the accident. David Mahony left a wife and five children and William Carthy also left a large family.

(e) Bridget Connery was a mother of thirteen children according to one newspaper report at the time. It is probable that she was the wife of Lawrence Connery of Rath who was a 78 year old widower in the 1901 census. At that time Lawrence Connery lived with two children John aged 35 and Mary aged 34 who would have been born close to the date of the accident in 1876.

The inquests on the ferry boat deaths commenced on Tuesday 3rd October 1876 which was three days after the accident and concerns were raised by the local clergy and constabulary about the delay in the inquest. There was no morgue in Youghal and there were concerns about the delay before the bodies could be removed for burial. The Head Constable Barry said he sent a telegram to the coroner on the day of the accident to let him know that an inquest was required but apparently did not receive a reply. The coroner gave the somewhat extraordinary excuse that he did not reply to the telegram because the last time he had sent a telegram the Government refused to repay him the cost!. The bereaved families were left waiting in Youghal from Saturday to Tuesday with no idea as to when the bodies of their relatives would be returned to them. The coroner was based in Fermoy and he went on to outline that he could not travel on the Sunday because he would be violating the Sabbath. He travelled to Midleton on the Monday before travelling on to Youghal on the Tuesday where he arrived at 5pm. Rev O’Neill CC said that the local constabularly had done everything in their powers to expedite the inquest and to help the bereaved who were gathered in the town for days. The bereaved had travelled a distance in most cases and had no idea when the bodies of the deceased would be returned to them. There were concerns that the bodies were decomposing as there were no morgue facilities in Youghal. A jury was eventually chosen who proceeded to view the bodies after which the bereaved were allowed to take the bodies for burial.

The initial inquest was carried out into the death of Ellen Budds and was extremely detailed with many witnesses called including survivors, eye witnesses, the harbour master at Youghal and a coastguard officer from Ardmore. The details are covered extensively in the chapter on Ferrypoint in this history and we will just summarise a few points here. There were extensive discussions concerning the condition of the ill-fated ferry boat of lessee Edward Connors who ran the ferry service. Captain Eastaway, harbour master at Youghal stated that there were too many people on the boat and that there was a heavy sea outside the pier head. He said that he thought that the boat was not safe to cross as she was too deep in the water. Patrick Mackin, a coastguard officer from Ardmore, stated that the ferry boat was completely decayed and that she might be fit for service in fine weather only. The Town Commissioners in Youghal attempted to dissassociate themselves completely from the poor condition of their ferry-boats which they were leasing to Edward Connors to run the ferry service. They stated that it was the responsibility of Edward Connors to maintain the boats even though it was apparent that no new boats had been purchased for possibly up to fifteen years on what was a very demanding ferry service. A number of witnesses maintained that they had asked Edward Gorman, the head boatman, to turn back to the safety of the quays in Youghal when it became apparent that the ferry boat was taking water but that Gorman maintained that “he would make the ferry in spite of the devil”. Edward Connors also owned a hostelry in Youghal and one of the witnesses stated that he had purchased drink for a couple of the boatmen in the pub. Questions were asked at the inquest concerning the sobriety of the boatmen and in particular whether the presence of alcohol was a contributory factor to the accident. The verdict of the jury was as follows:

“The jury are unanimous in finding a verdict of manslaughter against Edmund Connors, of the ferry boat in Youghal, in which Ellen Budds came by her death by drowning, on the 30th September, 1876, owing to the culpable negligence of Edmund Connors in the discharge of his duty as such lessee, and we therefore find that the said Edmund Connors did feloniously kill and slay the said Ellen Budds. We also censure the Town Commissioners of Youghal for their gross negligence in not having proper command over the ferry, and proper boats.”